Clarity and Resistance

[Based on a lecture first delivered at Florida State University in Fall of 2024]

••••

Imagine yourself outside in an unfamiliar landscape, a mixture of natural and man-made.

What is accessible to you first and foremost are your senses: seeing and hearing, being in a three-dimensional space, at a distance from certain objects. You may feel the ground vibrate from the cars passing by. You may feel the air pressure of the wind, and also hear it — which are the same things, but you perceive them differently. Finally, you feel gravity pulling on your own weight. Your resources are finite, you can not stand forever.

Around you are things you perceive, but their nature is not known to you. You know what a tree is — but unless you’re a botanist, you don’t know how it works. You know asphalt, you know what it feels like to touch it without touching it — but probably not its composition, nor the history of this particular road. You know you breathe, and also know that you breathe oxygen — but probably not the quantum chromodynamics behind it, and if you do know them, you may be wondering how much of it is real, and how much is just models.

So things are, at the same time, immediate and withdrawn. Heraclitus said that nature is always hiding — which is true, but it also presents itself so readily and completely.

Reading is like this. Writing is like this as well. All texts are at a certain distance, but words they use are apparent.

More importantly, the rules of such encounter are unclear. Landscape may have protected species; it may have invasive ones. It could hide the remains of a neolithic settlement right next to a gas station. You might encounter a wild animal. One doesn’t necessarily know how to behave around all these things, and if you reflect on this unknowing, it still gives you no guidance.

We could think of poems as just such encounters: in certain cases we just don’t know what to do with them — and while some encounters are vernacular, they can get you completely lost. Others aren’t vernacular at all.

••••

Difficult poets are not a populous group; neither is their readership.

Some of the people you may be familiar with are Paul Celan, John Ashbery, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Among the less known that I’ll be mentioning today are Jay Wright, Bei Dao, Arkadii Dragomoschenko, and two Brits from the extremes of old academia: Geoffrey Hill of Oxford and J. H. Prynne of Cambridge.

These are of course not all, and the somewhat strange paradox of difficult poetry is that while it is notorious, it is also surprisingly hard to find. You stumble upon T.S. Eliot naturally, as per his influence — but someone like Dragomoshchenko you have to track down from obscure contexts in a tradition that may not be in any way transparent to you. A very manual search.

Which brings us to yet another difficulty: ancient poetry, ethnographic materials, or just anything significantly removed — things that were never meant to be difficult for the original audience, but they are now. There’s an old wonderful joke about a dog that walks into a bar, and says “I can’t see anything, I’ll open the other one”. The joke comes from Ancient Sumeria. They found it hilarious. We don’t know what the joke even is.

••••

Paul Celan remarked that his writing has nothing to do with surrealism — that it was, in fact, realist. This is a common stance among both difficult poets and their scholarship, almost taken for granted, and in a good way — perhaps through some shared beliefs on the nature of poetry in itself.

In one of his late poems Celan calls out “the unreadability of this world” — fitting, since if the world is unreadable, then why should poetry be. It could be interpreted religiously, or anti-religiously, or metaphysically, and there is definitely, in Celan, an interest in all such readings — so when he invokes what’s broken about the world, the implication is it is broken primordially. But it doesn’t literally say that.

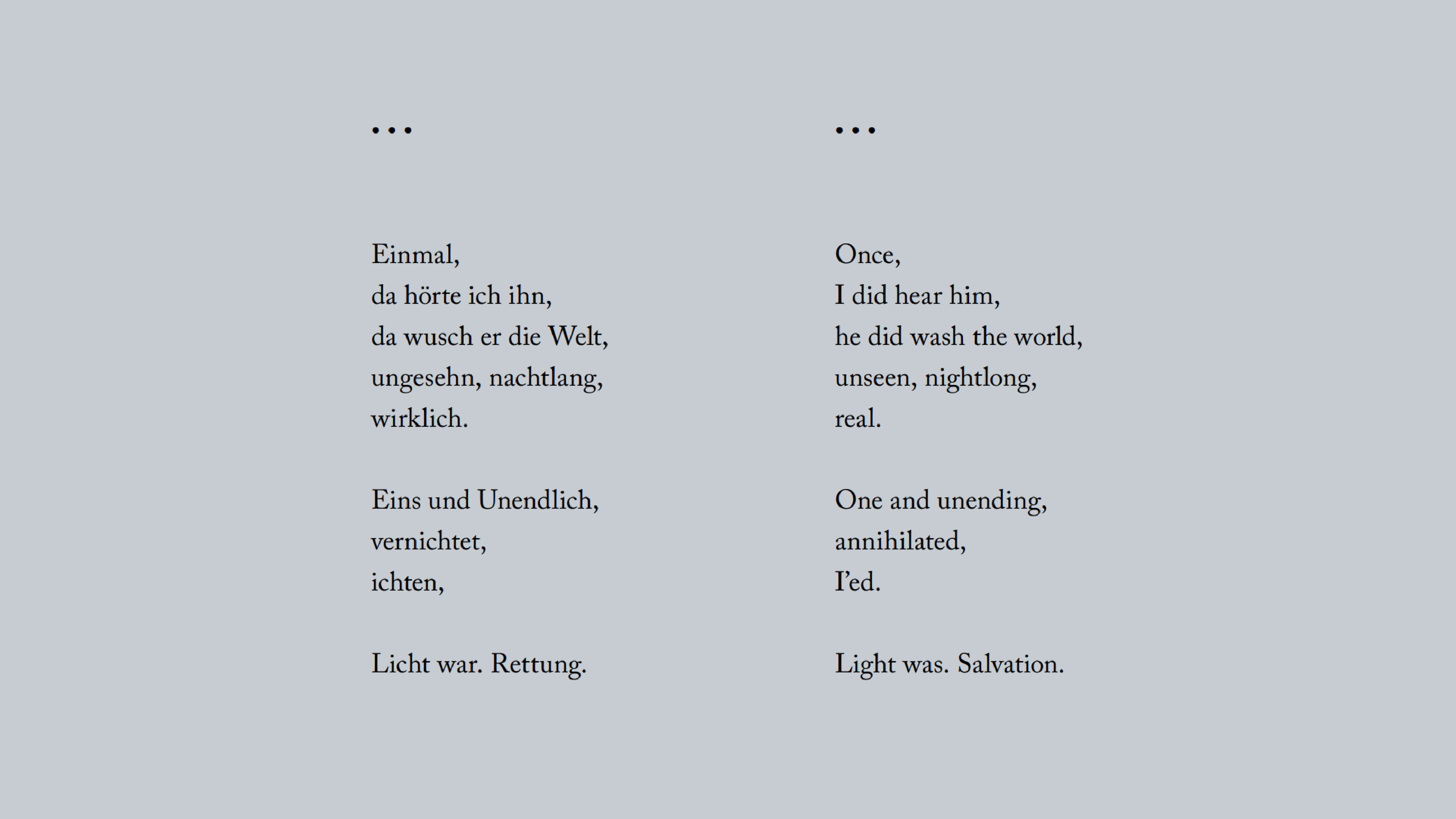

One often hears people ask whether such poems are puzzles to be solved; a better question would be what solving a poem would even mean. If poems really were puzzles, that would have made them coherent in just the same way mathematical proofs are coherent, which would make them all tautological. Compare a poem that simplifies into “the speaker is sad” to something like “Light was. Salvation”. The latter reads like a foundational proposition, something that could not be simplified further. When theorists say that medium is the message — this is the sort of writing they often mean.

Also among such writing is “The Meridian," a short speech Celan delivered when given the Büchner Prize in 1960 — a speech so influential its 15-page text was recently published as a 300-page volume analyzing the minute differences across its surviving drafts. In it Celan describes poetry as an encounter, in a broad sense — with either the author, the language, or just the poem itself — emphasizing a certain strangeness or perhaps several kinds of strangeness that can not be sorted out. And every strangeness is always and only its own.

••••

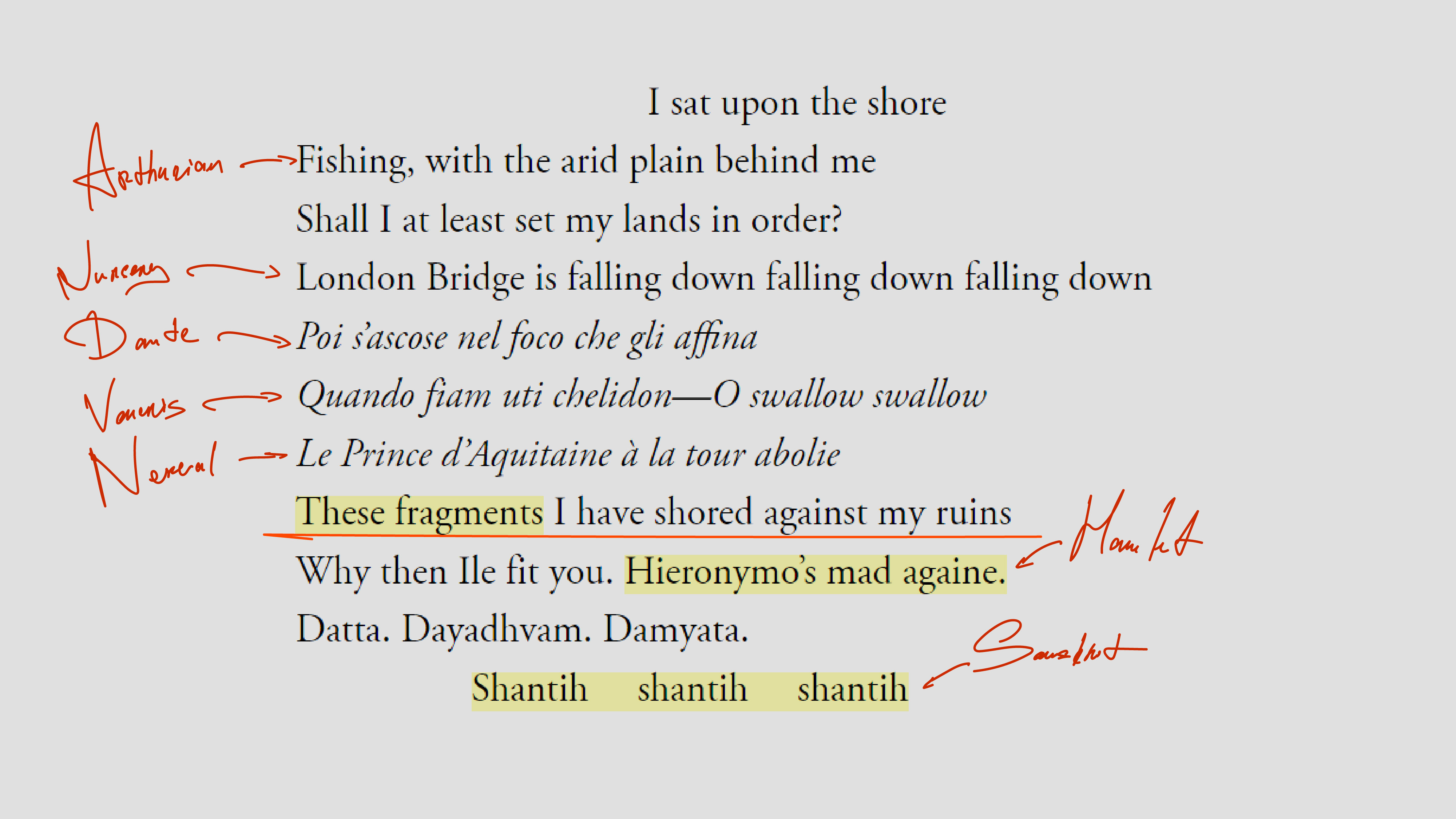

T. S. Eliot is taught as a high modernist innovator who changed all poetry forever — but it’s easy to misread what his innovation actually was. He mixes up blank verse with passages in Sanskrit, Arthurian references and dozens of other sources, and in between it all is a couple of married women trash-talking their married lives. Fun fact: “The Waste Land” was initially titled “He do the police in different voices”. Thank Ezra Pound it didn’t stick.

And while the multitude of voices appears complex, it is also very traditional. European poetry always quoted in classical languages. It always referenced folkloric epics. It always mocked provincial dialects. Eliot changed not what poetry did, but how it did it.

And while all of this overquoting may appear as a collage — it could be read as someone actually speaking. Fiona Shaw famously performed the full text of “The Waste Land” in Madison Square park in New York city, fully unsanctioned outside on the street, so I can attest that it works — and these lines read as something of an old man on his deathbed, speaking mostly to himself, and you mostly ignore him until he turns suddenly lucid, and says “These fragments I have shored against my ruins”, and quickly is lost again.

So while everything here is literary, it could have been something else, some kind of a “Rosebud” situation, a recollection of things past, and everything would be structured the same.

••••

Ezra Pound. If you’re ever in Venice, find the spot where he stands. It’s a really good spot.

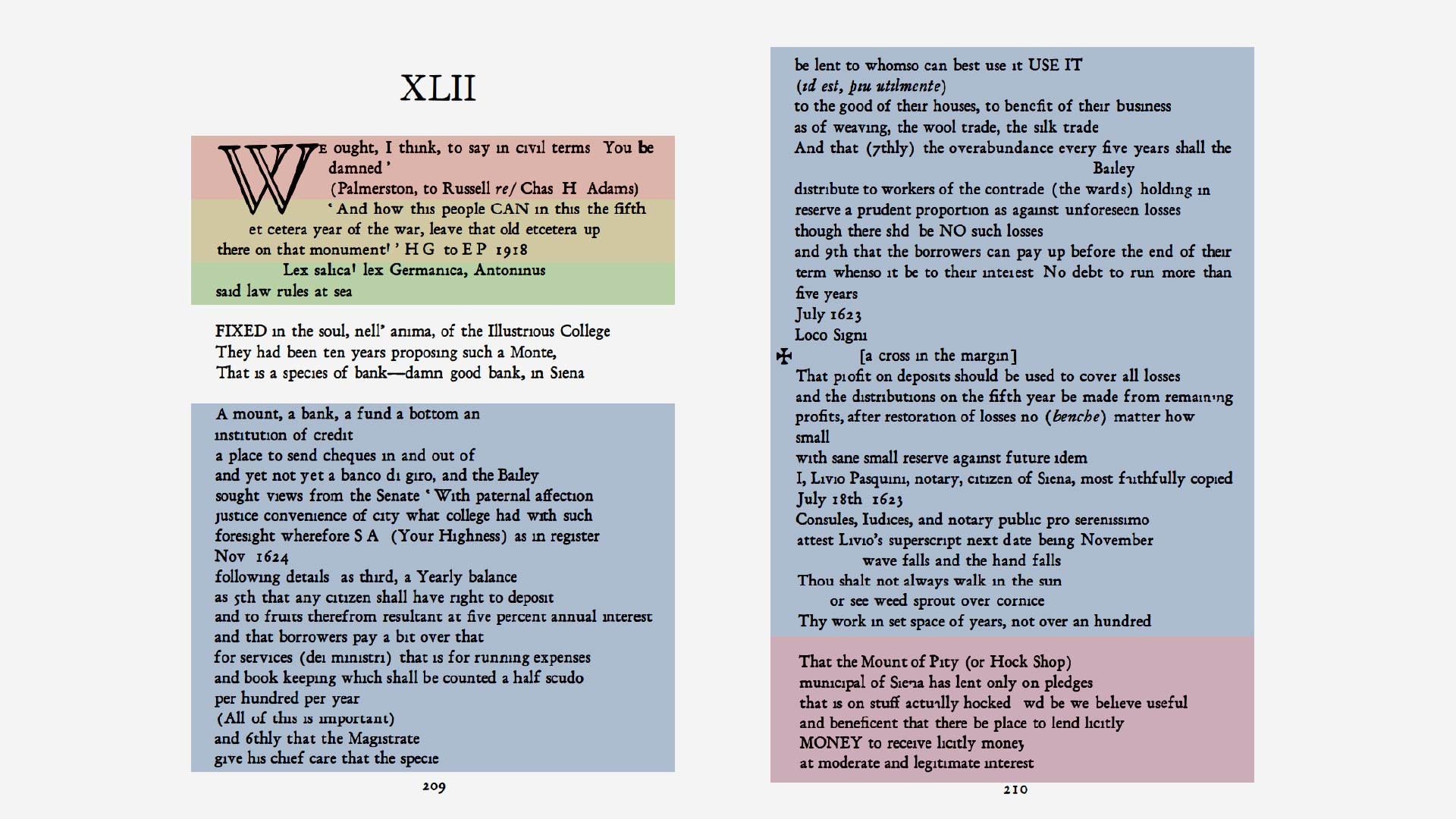

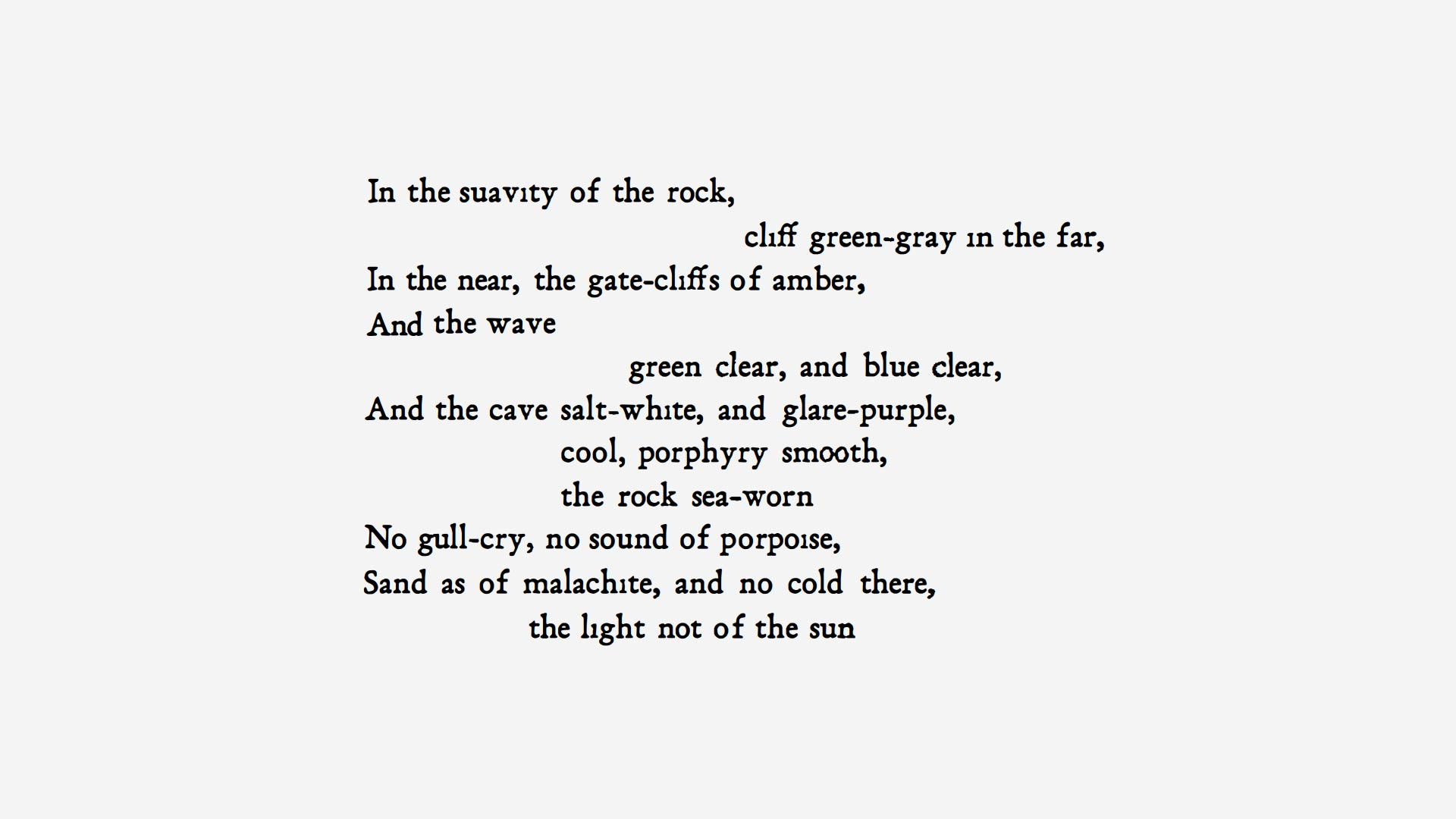

Pound is known most widely for Imagism, but was himself an Imagiste perhaps no more than a few weeks. The Cantos are his real project, and as such display some surface similarities to Eliot: containing, among other things, Chinese characters, musical notation, passages in ancient Egyptian, more accents, and, best of all, excerpts from political correspondence and the financial ledgers of 16th century Italian banks.

The difference lies in form and perhaps, timbre. Eliot composes. Pound uses an actual collage — extensive, sometimes multi-page inserts from the original sources — sometimes with striking lyricism in between. His mission was to understand history through minor, secondary and generally overlooked sources — not because they contain some secret illuminati stuff (though Pound definitely had a trait of conspiratorial thinking) — but because to the conventional history they’re kind of inconsequential.

In Canto XLII, for instance, attention is brought to the development of banking and, specifically, how banks create money ex nihilo through loans and interest, a topic that occupied Pound maybe a little too much. Contemporary controversies, as we all know, are often argued with scientific data that may or may not be properly used: think of satellite images or statistical tables — and if a poet takes on a subject where they have all this constantly in their head, they may not think of this as material. Pound shows that it could be, as is, unaltered in all but a few descriptions.

Still, Pound tends to use things you would rather not read. He may quote Dante too, but very obliquely. Not at all like this.

••••

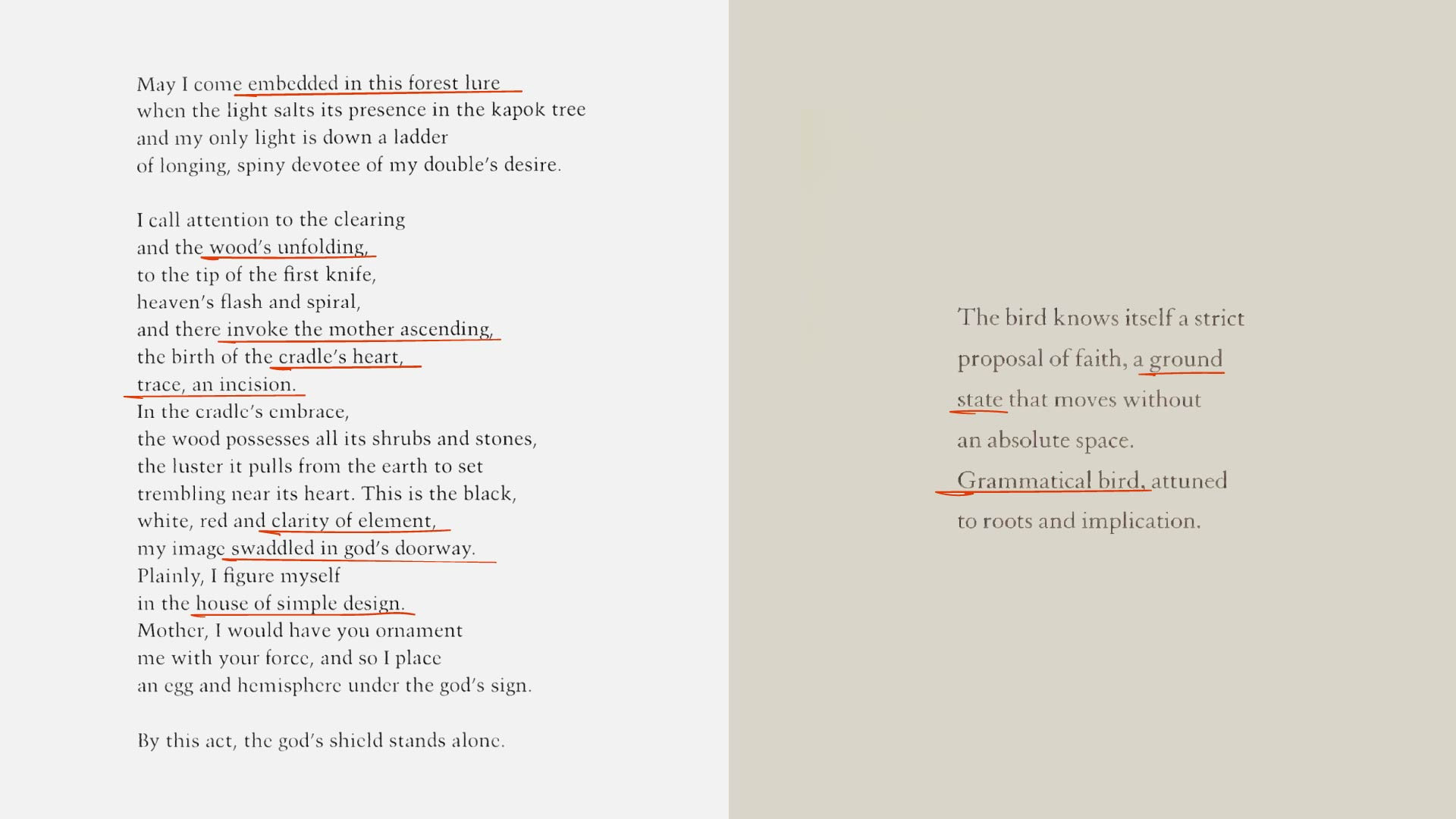

Jay Wright is known through the way he invokes traditional African contexts, most notably of present day Mali — and while this makes him hard to talk about without performing a lot of research, what is immediate in his writing is mythic cosmology presenting itself as language — which then branches out into spirituality, identity, the body and other themes. Notably, Jay Wright himself isn’t African, he’s from New Mexico, so all this is acquired context.

His book “The Double Invention of Komo” is based on the initiation rites of the Bambará people, which introduces an adolescent into adult life. The way they work is they place the initiate in a state of temporary social death, excluding them from the rest of whatever is going on: they may have to remain silent or abstain from food, people may be required to ignore their presence, and, possibly worst of all, being outside social order means people can hurt you without repercussions, which is resolved by a temporary exile. Specifically with this rite the initiate spends a week alone in the wilderness, learning new songs and dances taught to them by the trees, and when the time is due the initiate comes back to perform them back at the village.

Compare this to “Music’s Mask and Measure”, a book of uncharacteristically short poems that are his most linguistic and most physicist. Grammatical bird is an immediate giveaway, but the somewhat unusual addition is the ground state, a term from quantum mechanics that refers to the lowest possible energy of a molecule or an atom (since having no energy is impossible). Things of the world are also the things of language.

It’s not uncommon for ethnographic records to read like late modernist avant-garde — thus, in Jay Wright, it may sometimes be hard to tell whether any particular line is purely invented, or purely taken, or anything in between. It’s a precarious mode of writing: in which one does not necessarily always have to be right — but you can never afford to be wrong. A misguided veneer or misplaced irony, anything ostentatious or off-key, and the project immediately becomes counterfeit. Some will see it this way regardless.

••••

Bei Dao, at a first glance, would be significantly easier than any one of the examples so far — so why not put it in simple terms: he writes traditional Chinese narrative poetry in the mode of good old French surrealism, a wonderful example of nested cultural exchange: Chinese poetry had an incredible influence on Pound who translated it without meter or rhyme, thus developing a very particular western way of writing free verse that in turn had an incredible influence on contemporary Chinese poetry.

To the party line though this was an affront to both the working class and traditional values, and Bei Dao, along with many other poets of his generation, was dubbed “misty” as an official denouncement in the papers — and this is how the group has been known ever since.

So the lack of clarity here is projected and postulated. Poems themselves are not just clear in terms of tone — bitter, attentive and melancholic — but it’s not hard to decode in them the themes of endemic political violence: houses listening to people passing by, spontaneous heroism without a given reason, obligatory greetings and something strange equating the birds and the hunters of birds. The censors may not have appreciated the form, but they did correctly identify this as disagreeable. When tyranny sees poetry as a threat, perhaps one shouldn’t dissuade it.

And while ambiguity was handy in camouflaging dissent, Bei Dao didn’t abandon it after being exiled to the West. Personal style is compulsory — as something a poet is willing to surrender themselves to.

••••

Dragomoschenko is perhaps the most influential Russian poet of the present era, by which I mean that young acolytes finally stopped copying Brodsky, and for that we shall be eternally grateful.

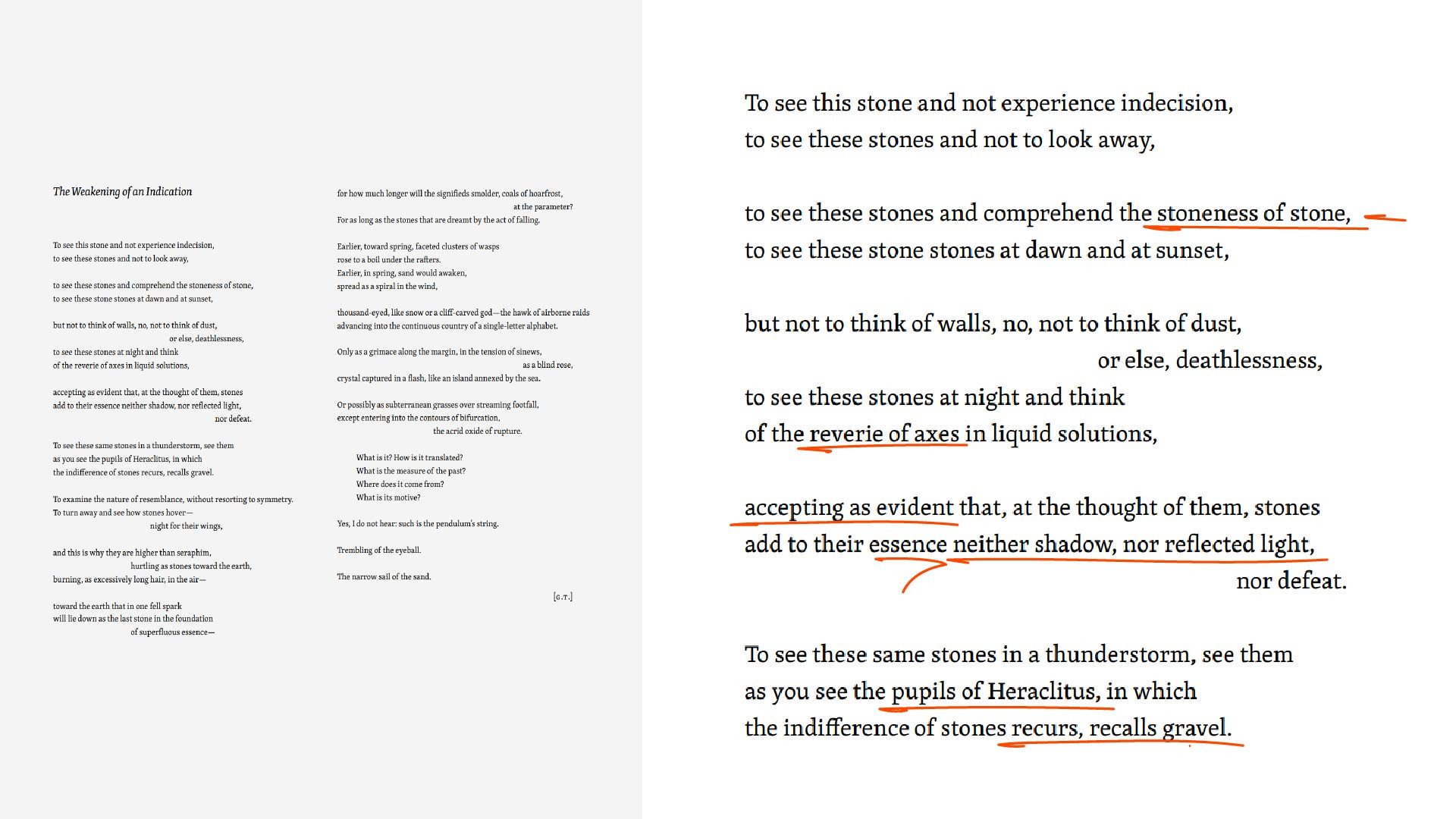

Dragomoschenko is most like a flow of consciousness, driven by observation and philosophical inquiry, above all in the philosophy of language — so, Wittgenstein — who famously said philosophy should be written as poetry anyway, so there. Stoneness of stone, essences, plenty of Heraclitis, things being accepted as evident: there’s enough material here to debate whether Dragomoschenko defends a pre-Socratic or a post-Socratic view — while an inner argument, if exists, would be entirely woven into the wordplay.

Compare also how some of the words are all too specific: defeat, indecision. Even in an impoverished surrounding, Dragomoschenko as always a bit baroque, which is something to note in assessing his overall tone. When things of the world become the things in oneself, it may be strange to see them again as things outside of oneself: looking at pupils instead of through them, on busts, not sculpted, but drawn, and presumably completely eroded.

And then there are the closing Brits. I like to use them in a pair, since they’re more or less the same generation, and there’s a sense of unspoken rivalry about the two, on the sole basis that they tend to attract the same readers.

••••

Geoffrey Hill. Looking here as if he was about to stab you with his knowledge of Milton’s political treatises.

Hill is incredibly historical, but while Pound was interested in economic and social history, Hill is primarily interested in moral history — or maybe I should say he’s mostly interested in the dead. He often invokes the dead, addresses the dead, and overall they are the primary subjects of his concern.

So, it’s ethics of past mistakes. The kind of feeling you get when you look at a medieval tapestry that depicts the common people killed in some lordly war.

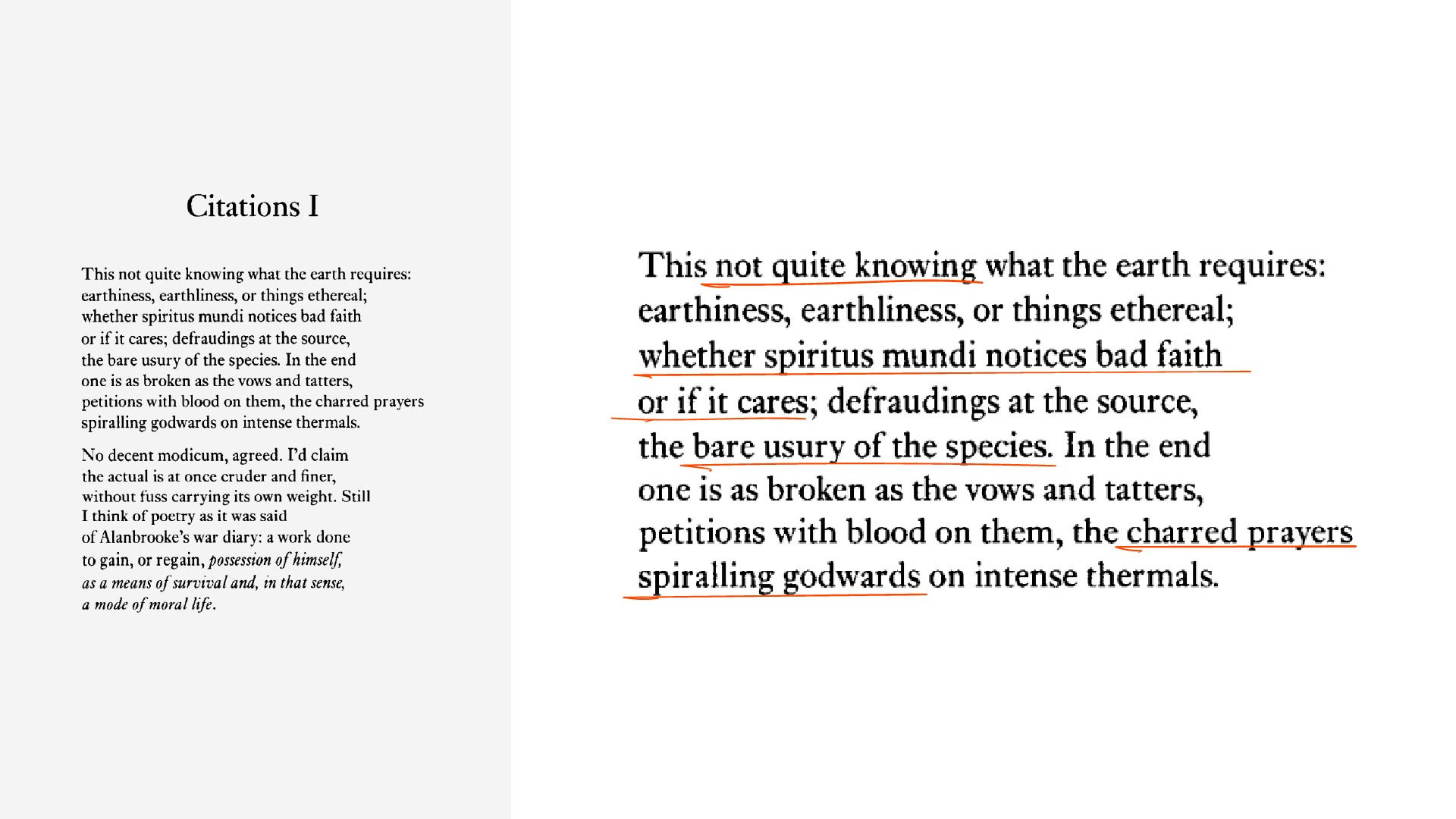

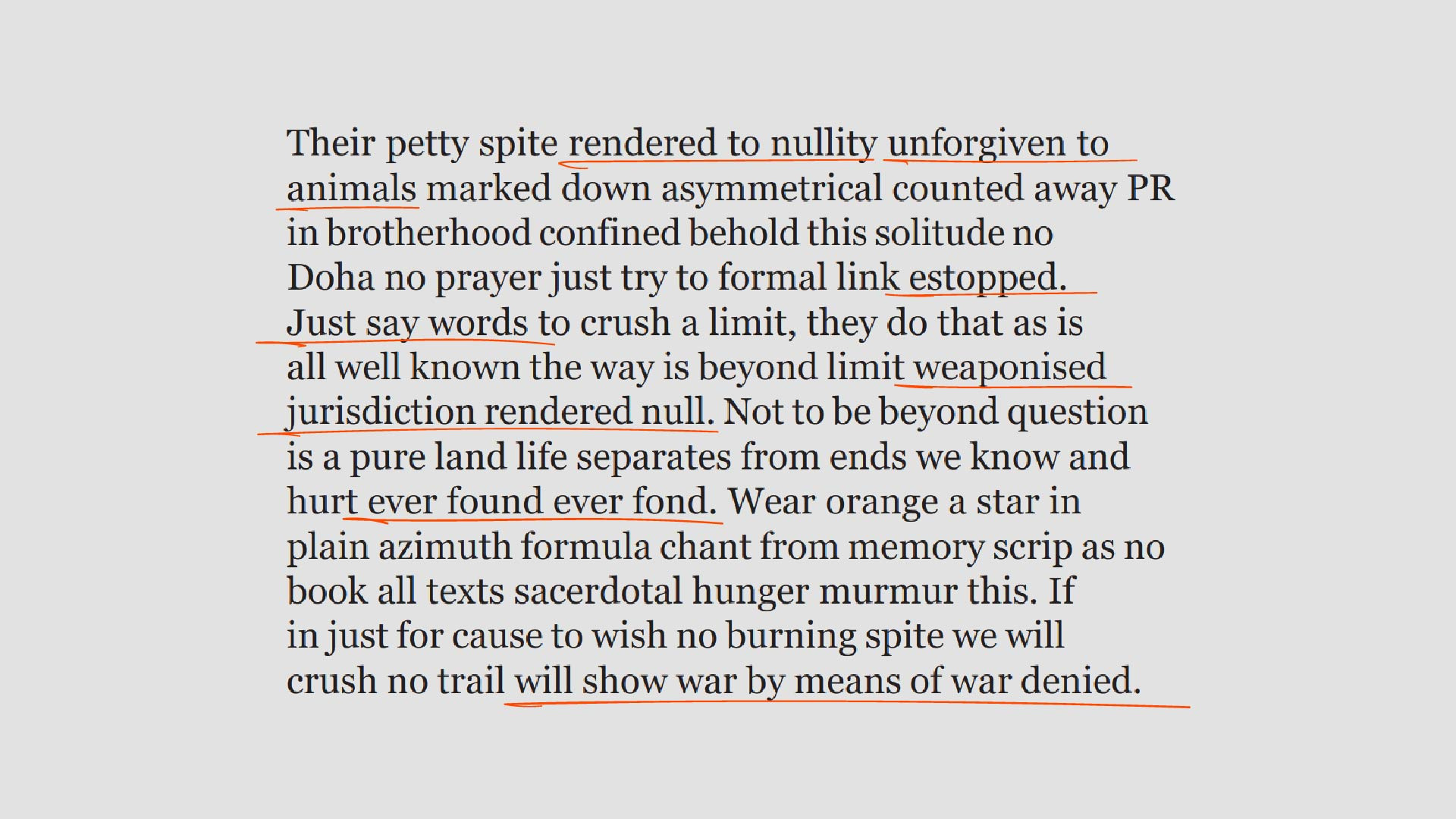

The example here is from “A Treatise of Civil Power”, which is a direct reference to Milton and his appeal to the English Parliament that is usually interpreted as a call for religious freedoms, but would be more accurately described as an investigation of people’s relationship to their oaths.

Notice the flow. It’s two sentences, but on a first reading it feels like it could be one or it could be four. Hill always jumps from one reflection to another, which is the manner of writing of someone who spent a lifetime pondering pretty much the same topics. Everything in between propositions has already been worked out and is largely irrelevant — in fact, it may be that the entire argument has been pushed into the background, and these are no more than a series of reveries surfacing as he’s thinking through all of it once again.

Of note also is that Hill is very traditional in his outlook — not the view as much as the texture of his expression, the kind of scorn you expect to find in an aging 18th century pamphleteer (which in this case I mean lovingly) — and yet it’s all expressed in a refined late modernist key. A stark and uncommon contrast.

Interestingly, both Hill and Prynne have things to quote on just the subject we’re on:

“We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. And we are mysteries to ourselves, we are mysteries to each other. One encounters in any ordinary day far more real difficulty than one confronts in the most “intellectual” piece of work. Why is it believed that poetry, prose, painting, music should be less than we are? Why does poetry have to address us in simplified terms, when if such simplification were applied to a description of our own inner selves we would find it demeaning? (…) Genuinely difficult art is truly democratic, and it is tyranny that requires simplification.”

Something to note here. Compare a sentence “this poem is difficult to read” to something like “this rock is difficult to lift” or, say, “it’s difficult to apologize”, and what the word does in each particular case.

••••

Lastly, J. H. Prynne. To give you an idea how others see his work, he was first described to me as an introduction into cryptography. He was somewhat mild in his early to middle work, but got entirely off the chart in his late stuff.

Prynne is non-traditional. His context is all over the map with scholarly understanding of some social and natural sciences, most notably geology, botany and economics. In fact, in some of his early work Prynne would, at the end of a poem, provide a list of scholarly sources in the manner of an academic paper. What’s significant is not only that he did that, but that he also stopped.

His late writing goes into the level of fragmentation that is frankly uncomfortable not only for most readers, but also for most writers. In a case similar to all our examples, you can always read this emotionally, and the impression it leaves is, again, that something is deeply wrong with the world, this time perhaps not metaphysically, but on a societal level, and that probably has something to do with why it has to be written this way. There is a philosophical justification for this, but I’m going to skip it for now — consider only that while you can interpret individual lines, one could focus simply on the mode of writing in general. The how of the fragmentation, rather than just the fragmentation itself.

Which leads us to one of Prynne’s most famous essays, and one that deals directly with the question of difficulty:

“If a philosopher is concerned to make intelligible the world around him, then its intelligibility must be of prior importance to the given fact that the world exists. (…) Theories that subordinate intelligibility— even in part—to some other criterion of importance are characteristically difficult to expound, and also to comprehend.”

In other words, if we prioritize being able to say something in an accessible way, we’ll need to sacrifice the things that can’t be easily talked about. And if we prioritize literally anything else — form, accuracy, integrity — it’s no longer as intelligible as it was.

Prynne suggests that we find an alternative to intelligibility — something he calls resistance.

“The world becomes intelligible to us—that is to say we can discriminate between different aspects of its existence—by virtue of the fact that it resists our activities in various ways. (…) [Resistance itself] comes nearer than any other differentiable quality to being completely inherent in the object, in the core of the other person’s distinctness from myself: the stone’s hard palpable weight is the closest I can come to the fact of its existence”

It is important to note how he invokes the natural world, things that we didn’t make. If you do any amount of hiking, you can think of a steep incline, to and above the treeline, or a long trek in the snow — something that invokes a persistent effort not because of any kind of animosity towards you, but by being in its natural state. A natural state of writing, if it prioritizes something above intelligibility, will be the exact same.

Of similar importance is that the pleasure one derives from it — is this state, and not anything behind it. It’s not a sense of conquering something through persistence and constant effort, and feeling an accomplishment afterwards. Few trails have actual destinations, and those that do, are usually overcrowded. This is closer to roaming. Again, imagine yourself outside.

••••

So what do we do with all this. One of the common features of all these poets is how none of them expect you to know all this: contexts, biographies, social codes. Moreover, they all kind of count that you don’t. The best analogy here is probably something like abstract expressionism. It’s got a ton of theory and history and context behind it, it is fully formalist, but it’s also entirely accessible exactly at the level of effort you are willing to give.

What all these authors are doing is poeticizing the things they care about on their end, and they proposition you to do it on yours.

This, of course, leads to the question of understanding, and I’ll have to give a strange example to illustrate this. Say, you connected with one of these poems here, or just pick any poem dear to you that you feel people might have trouble understanding.

Imagine giving such poem to somebody else. Usually nothing is going to happen, of course, but every once in a while you can see that the person got it. How can you tell that they did? What exactly is supposed to happen for you to know they got it? Is it something in their eyes? Could they tell you? What if they told you they did, but couldn’t explain what it was? Or they do, and it’s different from what you got, then what? Or if it’s the same — how do you know that it is the same?

Understanding is not something you do or do not have, because it is not an object — it is a vague sense that you can, to some strange degree, play along with whatever is happening here. That’s poeticizing the text on your end: you can look at a list of research papers on the glacial retreat in Norfolk, and think of it in a poetic way — and, by doing that, you ‘got’ Prynne, the hardest poet on the list. Just like that.

This, of course, leads to the question of non-understanding, but I’ll let you guys figure that one out for yourself.

Consider also how none of these poems tell you what they are doing — they’re just doing it. They are built a certain way without announcing the principles by which they are built. It’s like a math problem that doesn’t tell you the starting conditions, the formula or the solution, but only everything in the middle — and which is something extremely unusual for any communication to do. We announce jokes. Papers have abstracts. Magicians tell you what they are going to disappear. Even old novels gave you chapter summaries beforehand.

And this hints at something about poetry specifically, but also beyond that.

There is always a clarity to these things. Historical context may be hidden, but you would know it’s historical; language may be obscure, but you would know it’s obscure. A metaphor can be incomprehensible, but it would have tone.

So there is no singular kind of clarity, any particular set of qualities or things that, if present, render something accessible — and in an encounter, as one doesn’t find the kind of clarity one is accustomed to, it helps to ask what kind of clarity is there instead. This applies to texts, but is generally applicable to painting, film, architecture, and, I would argue, the things we did not make. Think back to Prynne writing about the heaviness of a rock, and how immediate it is.

Which is to say — clarity always goes hand in hand with resistance, if only we take resistance as a natural feature of literature. Personally I like to think about it as a certain responsibility — I have the subjects that I work with, and I can’t just say whatever I want about them. Writers who do not recognize such limits and feel like they can say whatever they want — ultimately have nothing to say.

And this, in turn, branches out into everything: ethics, metaphysics, ontology.

So: imagine yourself outside.

••••

You don’t know what all these things are. You don’t know if the feelings you get from them come from yourself or the things outside of yourself. You can’t stand in one place indefinitely, but you’re already standing on top of something. Moving elsewhere means stepping on something else, and you don’t know what you’re stepping on.

What does this act even entail? Is it power, a great chain of being, or collective suffering in a finite world? Is it a constant becoming? Nobody can tell you how to decide — but it might help to be careful all the same. Reading strange things opens you up to seeing other strange things, or considering the strangeness of what you’ve already encountered.

And most importantly, when you do consider it, you may discover that some of this strangeness, even in the most mundane things, is something you are unwilling to sacrifice for the sake of convenience. You may discover how it changes your attitude towards things in general — and what this might mean for your life from this point on. How would you treat other beings. What sort of stances would you be willing to take, what boundaries would you not cross.