The Act of Freedom & the Will for the New: On Childishness and Artistic Act

“A becoming and perishing, a building and destroying, without any moral accounting, in eternally the same innocence, is found in this world only in the play of the artist and the child. And just as the child and the artist play, so does the eternally living fire play, building up and destroying, in innocence — and this game is played by the Aeon with itself.”

Friedrich Nietzsche,

“Die Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen, “

Adults tend to draw a distinction between themselves and children, sometimes feeling the need to maintain this divide. A child’s actions can often seem incomprehensible, occasionally endearing, fragile, touching, and sometimes even strange or uncanny. But why, if we were once children ourselves, just in a different temporal continuum? This distinction is quite mysterious and, upon reflection, somewhat absurd. Yet it underpins comparisons when it comes to something irrational, impulsive, or naive — qualities often described as infantile. The idea of imagining horizontal relationships and defining the other — the child — as an equal to oneself is not obvious.

The discourse, shaped by millennia of Western European philosophy, defines childhood as a phase with certain qualities. These qualities of childishness have evolved according to socio-historical and cultural concepts over time: in the Middle Ages, children were considered “little adults,” while in the Romantic era, they were seen as embodiments of a closeness to nature. Today, the dominant view reflects what could be broadly termed the "Aristotelian conception" of childhood: an immature form of organism development with the potential for maturity. Enlightenment philosophy refined this idea, establishing a linear narrative for human development, one that must conform to various social norms and statuses, positioning the educated adult as the pinnacle of progress. This framework has, among other things, given rise to a series of centrism: Euro-, anthropo-, and, notably, adultcentrism.

For philosopher Gilles Deleuze, for example, the “adult” worldview, characteristic of Platonic, Aristotelian, Kantian, or Hegelian thought, was terrifying or simply “incomprehensible.” The concept of the "immediate," of immanence, is extrapolated to the logic of existence for any individual, in contrast to the mediated (adult) mode of being of the mind. Philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva touches on the same concept of immediacy when she develops the idea of “pre-language” — a state in which a child exists before fully mastering language, allowing them to perceive the world without conventions and filters, as it truly is. Entering the realm of language, we enter a space of agreement, shared by members of society and accepted by them, the bearers of language. Childhood can be seen as a special space of becoming, where adult normative systems do not operate, allowing it to be viewed as a site of creative freedom and potential, even resistance. This appeal to processes that, at first glance, seem distant from rationality, and are closely tied to unconscious structures, also characterizes the act of artistic production.

The qualities that distinguish the "adult" and "child" roles won’t be the focus, nor will comparisons between them be drawn. It’s far more interesting to explore the essence of processes and acts of childishness in their independent and immediate forms. Childhood, according to philosopher Walter Benjamin, is a time when an individual exists in a state of pure perception, free from pragmatic constraints. In this sense, the child is also a Baudelairean “flâneur,” exploring the world directly without being burdened by social or other obligations. Benjamin, who had a deep interest in childhood studies, was particularly fascinated by the process of play. This process is free from the need to cultivate a “better person” and represents an original way of understanding the world, not focused on linearity or the pursuit of creation and physical integrity. He applied this model of child’s play to his analysis of historical processes and cultural production.

When studying play, Benjamin highlights the binaries tied to childishness, but he views them not as inherently good or bad but as necessary aspects of a singular process: mimesis and destruction, humor and cruelty, disassembly and reassembly, collecting and rupture. These, he argues, “in a dialectical sense, lead to the acquisition of sovereignty, where closeness to history or the strange, analytical disassembly, and stable new creation complement each other.” According to Freud, and Nietzsche as well, destruction and creation are deeply intertwined in human nature: sometimes the first can only lead to the second. In contemplating the eeriness and cruelty of childishness, Benjamin finds a subtle logical solution: childishness can sometimes be marked by the concept of “barbarism,” in the sense that barbarians not only suffer from a “poverty of experience” but are driven by it — meaning that necessity leads them to create something new. A tower built from blocks must first be destroyed before it can be rebuilt, — and the managed moment of destruction and repetition in children’s play, the liberating impulse, has a culture-creating power. Paradoxically, Benjamin connects childish repetition with the potential for free play, unconstrained by templates, rules, or traditions, as it emerges from the enjoyment of the process and the pleasure of victory. Here, repetition also serves to manage “anxiety-producing experiences” through these very victories of creation: “erschütterndste Erfahrung” (the most shocking experience) transforms into “Gewohnheit” (habit). Deleuze later notes that repetition is a way of renewing eternity continuously. It becomes a means of exercising creative freedom and freedom of being in general.

This perspective, allowing us to focus not on qualities but on the processes in which children are engaged, and on the harmonious contradictions of these processes, enables us to perceive the concept of play as a special form of cultural production. It opens new horizons for understanding childhood as a particular, unbiased, yet complex view of the world. This is a unique perspective: according to Deleuze, the child’s act is connected with resistance to the rules of the adult world. He asserts that at the core of the creative act lies resistance to the informational paradigm through which power operates in societies. Here, resistance is the release of the capacity for life.

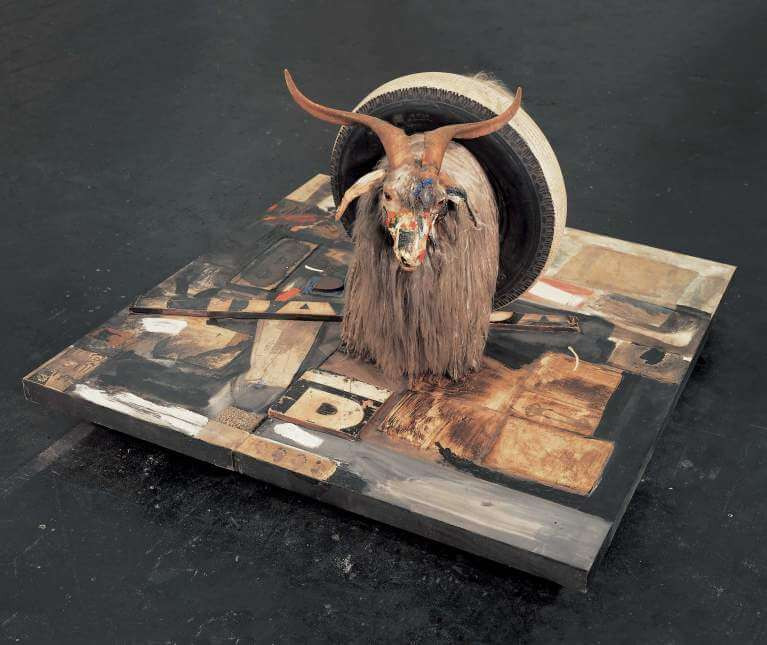

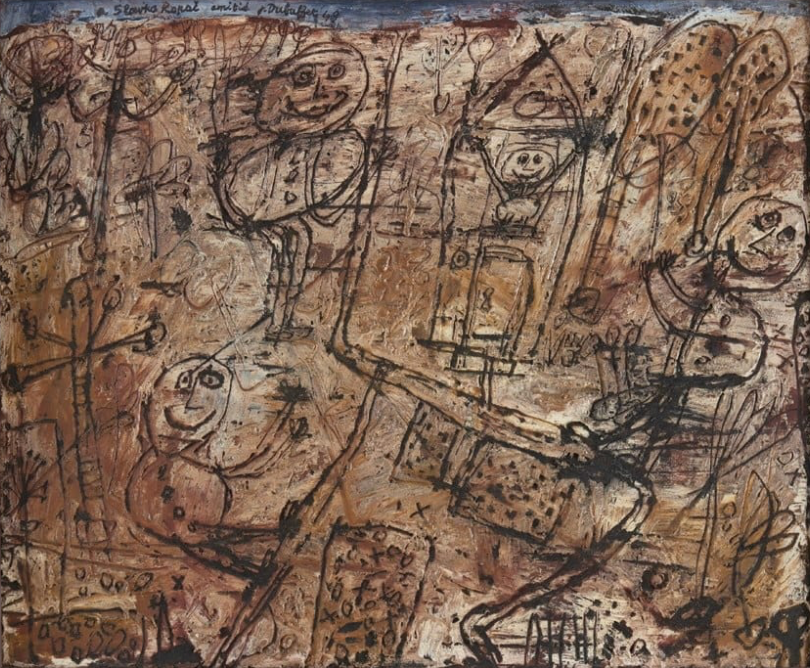

Much like child’s play, the artistic act encompasses elements of analysis (which sometimes equates to destruction) and creation. It allows for the integration of new knowledge while processing existing experiences and manifesting the unconscious in conscious reality. The division of the world into parts and the re-creation of a new order — which may appear chaotic — reveals its pure logic, a desire to know the world as it is. The intuitive gathering of objects, characteristic of a child (an ideal bricoleur!), truly resembles bricolage. Here, we can observe parallels with the avant-gardists and Dadaists, who employed similar principles: collages, assemblages, and DIY projects made from available materials. The things that, for one reason or another, end up in their “collection” — which at first glance appears chaotic and barely attributable to the gaze of ordinary logic — are essentially the process of linking the unconscious with the material world. They represent working with the imprints of the Real and searching for ways to understand it and construct new orders. If we draw an analogy with cultural processes, the path of play allows not just breaking with the past or destroying it; it enables placing it in new contexts, restoring it in new configurations, preserving its relevance while moving forward.

It is this bricolage logic, according to Claude Lévi-Strauss, that functions like a kaleidoscope, creating a new imaginative unity from the fragments of past experience. Mimesis, encountered by the child in the process of learning, is not “forced” or predetermined; it becomes a product of an active capacity for resemblance, implying a difference from the original. This active capacity for resemblance and creation mirrors the artistic act, where the artist, using various materials, creates unique images and forms while exploring both personal and collective unconscious processes. The materials of bricolage can be artifacts from the real world, as well as associations and dreams — the unconscious that contemporary art works with especially closely. Dreams and their interpretation, as the “royal road to the unconscious,” do not fit into rational or linear logic; they form a collage of images and associations arising in everyday life and entering the realm of the unconscious.

It is through this “reassembly” of the world that rebellious and free modern art of the early 20th century began to resist the outdated world of traditional culture and respond to global catastrophe, “resistance to the informational paradigm.” Dadaism, with its emphasis on absurdity and chance, sought to dismantle familiar logical constructs and forms by turning to collage and assemblage. The Cubists and Fauves literally broke the world into pieces, coarse and literal, in order to reassemble new worlds from them — a harmony from former chaos. Surrealism, inspired by the development of psychoanalysis, deepened this approach, using methods of automatic writing and associative thinking to extract subconscious images and ideas. Art brut, representing works by untrained artists, emphasizes immediate and authentic self-expression, working directly with the unconscious. It is free from formalities: status, education, occupation, and independence from commercial interests. It’s impossible not to create. Incidentally, modernists were also deeply interested in art for or by children. On one hand, avant-gardists and Dadaists adopted methods that children use in their leisure time (puzzles, collages, unconscious writing); on the other hand, children were considered “outsiders” and intrigued artists as expressers of the pure unconscious through their unique artistic works. Undoubtedly, this interest in the processes and mindset of children, in the very essence of childishness, was tied to the desire to build a new world from the crumbling old one — to build a new tower from wooden blocks. This defined the development of contemporary art in its current form: free, immanent, non-conventional, independent, and open to the new.