НИ СЛОВА О ПОЛИТИКЕ / NOT A WORD about POLITICS (Introduction by Joan Brooks + два новых текста)

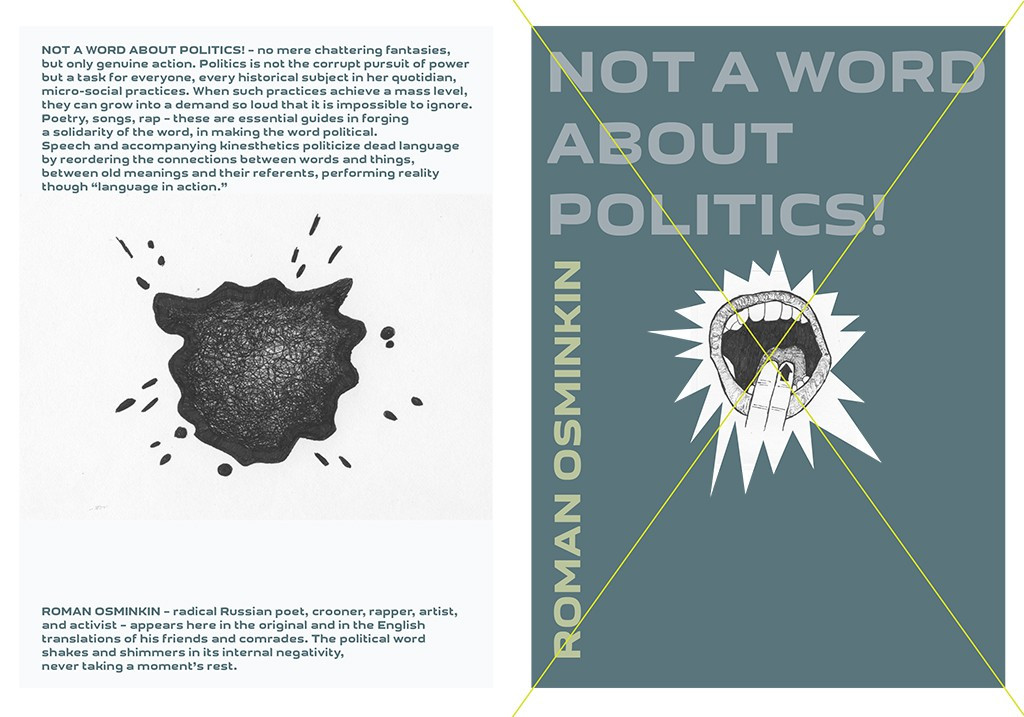

Скачать билингвальную книгу Романа Осминкина "Ни слова о политике // Not A Word About Politics!”, NY: Cicada Press, 2016. — 280 p. Roman Osminkin. Editors: Anastasiya Osipova, Joan Brooks, Matthew Whitley. Translations by Olga Bulatova, Cement Collective, Jason Cieply, Ian Dreiblatt, Brian Droitcour, Keith Gessen, Ainsley Morse & Bela Shayevich, Anastasiya Osipova, Jon Platt, David Riff. Cover design and illustrations: Nikolai Oleynikov and Anastasia Vepreva.

[Introduction]

Communism Isn’t An Ideal

by Joan Brooks

Roman Sergeevich Osminkin is a man of many masks. In his stage persona he oscillates between the hyper-macho look of an unemployed street thug — track pants, wife-beater (in Russian known as an “alcoholic-er”), flexed muscles — and that of a mild-mannered member of the intelligentsia — jacket, cap, sometimes a beret, glasses just for show (as he says, “intellectual frames without academic lenses”). But his brash masculinity is always compromised by the falsetto flights of his gender-ambiguous voice and the bony frame protruding from underneath his muscles — he is quite emaciated in fact, maybe even malnourished. The intellectual persona seems equally peculiar amid the aggressive fury of songs like “Bloodbath,” when he takes on the perspective of Russian revanchism. In all his guises he is a lithe, even acrobatic dancer, twisting every sinew and contorting his face in rhythm with the beats and synth leads. But his gaze is usually blank, as if to say, “Here I am, a screen for your projections.”

In life Osminkin is one of the most polite people you will ever meet. Sometimes he even comes across as formal and cold, but then he’ll lavish on you a tenderness that seems almost alien in its warmth. He loves singing loudly and prancing about in the streets. He dotes on his mother. He is an expert shoplifter. He always prefers walking to taking the bus, and it’s never clear what the motive is — reluctance to pay the fare, obsession over his fitness, or some psychogeographic extravagance. He is an urbanite through and through, but his roots are in the peasantry (the rich agricultural regions along the Volga River in Russia and in the Zhitomir region of Ukraine), and he loves talking about the food back home — fresh milk, blood sausage, luscious vegetables. But then some days he might not eat anything, save an apple and a bit of stolen cheese — and heaven forbid any food before bed. He claims never to get depressed– “fifty grams of vodka and I’m ready to go” — but his close friends know how difficult he can be when the atmosphere isn’t quite right or his batteries are low.

Is there a center of consistency behind these fluctuations? Whatever comparisons one might make to other eccentric Russian icons — like the poet and artist Dmitry Prigov, or the musician and actor Petr Mamonov — there is a distinctiveness here, which always announces the presence of Osminkin. He is utterly unique in his body, his movements, and in the wild concatenations of symbolic codes he manipulates, mixing deadpan irony with flashes of genuine passion in the most unexpected ways. But then again, maybe he’s just a phantom after all.

Born on November 7, 1979 — on the anniversary of the Russian Revolution and exactly a century after the birth of Trotsky — Osminkin came of age amid the turmoil and deprivation of the Russian 1990s, as neoliberalism wrought its own revolutionary terror in the form of economic “shock therapy”. Osminkin says most of his classmates from school are dead. But poetry saved his life.

Now he is a central figure in the vibrant, if for the moment depressingly marginal, Russian community of leftist artists, writers, activists, and intellectuals. He shares his comrades’ belief that creative work must be linked to activism and the building of an oppositional community. He was a member of the Laboratory of Poetic Actionism, which combined video-poems (distributing the poetic word into three dimensions) and more aggressive interventions into public space. He was active in the Street University movement that emerged in 2008 after St. Petersburg authorities tried to close one of the city’s few remaining progressive institutions of higher learning. He is a regular contributor to Translit, the most influential leftist journal of poetry and poetics in Russia. He frequently collaborates with the Chto Delat group and other artistic collectives. His musical project, Texno-Poetry, performs regularly at festivals, art openings, and benefit concerts, often alongside Kirill Medvedev’s Arkady Kots band. He lived in the famous commune on Kuznechnyi Lane in St. Petersburg, a buzzing hive of avantgarde antics and metapolitical conspiracy. He is a member of the Russian Socialist Movement and a Ph.D. student at the Russian Institute of Art History, writing a dissertation on participatory art and its popular manifestations beyond the art world. He has three books: Comrade-Thing, Comrade-Word, and Texts with External Objectives.

In this volume we have collected all extant English translations of his work, the bulk of which were produced for specific occasions as subtitles for performances in Europe and America, and we have added several new ones.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Osminkin is not interested in the high avantgardism of language poetry and still less in intimate phenomenological lyricism. Instead, his work is rooted in the elusive irony that dominated underground Soviet culture in the 1970s and 1980s (a rhetorical strategy that often extended into the practices of daily life, and which is becoming harder and harder to find these days, as Russia becomes increasingly integrated into the global corporate order).

In many ways his method can be characterized as the performative erosion of false or failed dialectical encounters. His “You know how sometimes…” cycle typically turns on some unresolved contradiction between communicative codes (“you turn on the TV and they’re all praising Putin… you get online and they’re all talking shit about Putin…”), which he then proceeds to resolve, not through synthesis, but through a peculiar form of “tarrying with the negative,” using irony to preserve and perform an underlying restlessness, anticipating a true confrontation still to come (“then sometimes you pick up a book… and you think My God there are some fundamental human values left on this earth after all…”).

In other texts he displays a virtuoso generative capacity, creating lists and series (e.g., “You know the Slavs and the Tatars…,” “The Awakening of Sovrisk,” and the titular poem of our anthology, “Not a Word About Politics!”), in which syntactic parallelism focuses lexical diversity toward an incantatory explosion of the dominant ideologeme from within. By the time the series finally ends and retroactively defines itself (typically with a feeling of jubilant emptiness), the crowd has already become one with the text, internalizing its generative structure, at once captured and blown apart.

Or we might consider the unresolved contradiction between his own methodological declarations — in which poetry hijacks the machinery of language, seizing and dealienating the surplus of communicative value it constantly produces — and the recurring theme in his verse of the contemporary poet’s own alienation and longing for an impossible alliance with the (long since depoliticized) proletariat. Yes, this may be just another fragment of ideology the poet must colonize and reinvent, but it comes up so often, and Osminkin is after all a kind of bastard son of Gramsci’s organic intellectual, emerging from the cataclysmic leveling of Soviet classlessness (keep dreaming that unfulfilled dream) into total lumpenization.

Which brings us to the most important question. What political horizon do these texts inhabit? What is the status of Osminkin’s communism? Recently the influential scholar of Russian postmodernism, Mark Lipovetsky, has argued that the core (or central emptiness) of Osminkin’s performative poetics is an insoluble contradiction between the unified political subject of communism, grounded in party discipline, and the counter-cultural, elusively ironic, “shimmering” subjectivity he inherited from the late socialist underground. Osminkin himself has responded that he is much more interested in the contradiction between performative presence — the body of the performer — and the mediatic flows into which linguistic play is constantly subsumed. This is where the subject shimmers between presence and absence, identification and irony, affirmation and subversion.

My own feeling is that Osminkin’s poems are more than just a site for contesting incompatible utopias — the utopia of power and ideology and the utopia of ideology’s endless dissipation. They are also more than a site for the throbbing of creaturely life under the tyranny of the signifier. For me, Osminkin is an adept of dialectical anticipation, preserving the communist horizon as something we can only approach obliquely, not as an abstract ideal, but as a vibrant presence in our daily life, in the richness and confusion of our language. Communism today requires more than direct action and militant fidelity. It also demands the intensive labor of de-alienating subjectivity through its dispersal into the manifold of objects, both lexical and physical, comrades and enemies, into the array of ossified subject positions that must be deconstructed and revived, and into the affects that can be deployed either to block solidarity or bind us together into a collective body of anger, desperation, and love. Such practices of de- and re-subjectivization are essential as we prepare for the renewal of militant struggle.

Roma’s phantom center is a fire — at times blazing, at times quiet and warm — and it is uncannily effective in giving strength to those who dance around it. He asks us to sweat out the surplus value of language, to feel it dripping on our bodies, drunk on wine, hungry and tired, next to some desolate Petersburg monument begging to be brought to life. If you ever get a chance to let yourself go at one of his performances, don’t miss it. If love can become a politics, this is how it works. Untilthen, read this book.

***

***

Специально для Syg.ma Роман Осминкин представляет два новых, ранее не публиковавшихся, текста.

25 октября 2017 года на конференцию по случаю 100-летия Октябрьской Революции в Европейский университет съехались левые философы со всего мира.

Вдруг поступает информация, что Мраморный дворец атакуют казаки и православные фундаменталисты.

Участники конференции решают оккупировать Европейский университет, баррикадируют входные двери и коридоры.

В спешном порядке на повестку выносится вопрос о том, чтобы дать отпор черносотенцам и хоругвеносцам.

Единогласно принимается решение держать оборону Мраморного дворца и университетского дискурса до последней капли профессорской крови.

В подвалах Университета обнаруживаются запасы воды и продуктовые наборы для кофе-брейков.

Ректор Олег Хархордин сообщает, что под паркетом конференц-зала им были заранее схоронены боеприпасы.

Почетный гость конференции Славой Жижек влезает на кафедру как на броневик и громогласно заявляет: Товарищи, настал момент, когда Европейский Университет должен быть превращен в агитпункт, в факел, который светил бы университетам всего мира.

Слова Жижека утопают во всеобщем одобрительном гуле и овациях. Жижека избирают председателем Военно-революционного комитета, но так как Жижеку регулярно нужны инсулиновые инъекции, то при нем создают пост зам. Председателя на который тут же выдвигается теоретик агонизма и бывшая активистка Occupy Wall Street Джоди Дин.

Джоди Дин страстно оглядывает зал и заявляет: Товарищи, нам необходимо срочно создать оперативный Штаб обороны Университета.

Слова Джоди Дин также утопают в одобрительном гуле и овациях.

В

Борис Гройс вызывается быстро набросать основные пункты кризисного Устава Университета на военном положении и предлагает название: «Университет в осаде: Мейясу или Сталин?».

Философ Артемий Магун выкатывает с чердака Дворца старый пулемет по ласковому прозвищу «Марксушка», а философ Оксана Тимофеева протирает его машинным маслом и заправляет пулеметную ленту «ГД-ФМ» (Гегелевская диалектика-Феноменология Духа).

Филолог Илья Калинин натирает до блеска свой наградной маузер, потрясая вихрастым чубом и приговаривая словами Виктора Шкловского: Наша изломанная дорога — дорога смелых!

Илья Будрайтскис и Илья Матвеев налаживают университетскую радиостанцию и записывают подкаст: «Дневник Сопротивления».

Философ Йоэль Регев констатирует: вот и настала пора превратить Империалистическую войну в войну Гражданскую!

Философ Кэти Чухров отрывает от своей блузки кусок рукава и накладывает повязку на кровоточащую рану молоденькому доценту, напевая старую мегрельскую колыбельную.

После трехсуточной осады казаки и православные фундаменталисты отступают, понеся большие человеческие потери.

По самодельной радиостанции участники обороны Европейского узнают, что на их сторону встали СПБГУ, Высшая Школа Экономики, РГПУ им. Герцена, ИТМО, ГУТ им.

***

что ты чувствуешь когда видишь

как народы разных стран массово выходят на улицу

чтобы высказать своим телом и голосом право на

(а кстати право на что?)

народы разных стран выходят на улицу по разным поводам

с разной степенью воодушевления и надежды, гнева и возмущения, упорства и безысходности:

беларусы за собой убирают мусор

кыргызы жарят конину на уличных кострах

украинцы жгут покрышки

американцы сносят памятники и штурмуют капитолий

греки забрасывают полицию сигнальной пиротехникой

грузины танцуют рейв на митинге

We Dance Together We Fight Together

и еще раз для ритма

We Dance Together We Fight Together

французы бьют витрины банков и магазинов

армяне спят в палатках на площади Республики

турецкие дервиши кружатся на площади Таксим

хабаровчане мирно ходят маршем в минус тридцать

(а в Якутске и в минус пятьдесят!)

башкиры защищают священную гору Куштау

жители Сургута обнимают свой парк

(и обнимают здесь не метафора)

иркутские зэки вскрывают себе вены

беларуский художник Роман Бондаренко пишет в чат «я выхожу»

и выходит чтобы не вернуться

нижегородская журналистка Ирина Славина поджигает себя…

видишь как много разных образов

языков гендеров поколений разрезов глаз и цветов кожи

выбрасывает на гладь твоего монитора

(кстати, а кто выбрасывает?)

или эти образы как тюлени

потерявшие ориентацию и замучанные болезнями

сами выбрасываются на жидкокристаллический берег

а вслед за больными выбрасываются и здоровые

силясь ухватиться хоть за один битый пиксель.

Так что же ты чувствуешь когда видишь как народы разных стран

выходят на улицы своих городов?

находишься ли ты на безопасной дистанции как философ Кант

сидя в своем прусском доме и глядя на бушующую балтику

чувствуешь возвышенное?

нет не так

ты чувствуешь Возвышенное?

Ты же начитанный малый и знаешь

что революция включает в себя зрелище революции

что она не происходит сама по себе

а должна быть явлена для глобального зрителя

(может быть ты и есть этот глобальный зритель?)

какую революцию сегодня принесет

стремительный оптический пучок

на чем задержится зрачок

какие возыграют страсти

в интерпассивной симуляции участия?

слишком много вопросов для одного человека

(когда я выбрасываю пластик то напеваю песню про то что пластмассовый мир победил и этот пластик переживет меня на много тысяч лет как взятый в долг антропогенный след)

Так что же ты чувствуешь когда видишь

как народы разных стран… (и далее по тексту)

испытываешь ли ты как

что-то вытесненное бесформенное дополитическое

завязывается внутри и

разливается по твоему телу оголтело

это еще не солидарность, а лишь (голый?) аффект

солидарности ли?

такой аффект который

имеет обратной стороной фруст-

-рацию

некий хруст костей нечто хрустящее

добро пожаловать в резиновое настоящее

слушай

скажи

а вдруг народы твоей страны завтра выйдут также

и что тогда?

присоединишься ли ты к ним

/ох уж этот невозможный выбор без выбора

ох уж эти предадаптивные способности масс/

или ты подождешь когда на улицу выйдут столько людей что тебе

будет не страшно выходить вместе с ними быть рядом с ними кричать рядом с ними

сколько тебе надо для преодоления страха?

10000

100000

1000000?

ну вот реально миллион людей и тебе уже не страшно?

вас уже не задержит не арестует не остановит никакая полиция никакая власть никакие светошумовые гранаты не заглушат вас потому что вы здесь власть вы та самая стихия та самая буря на которую ты только что смотрел из окна глобального ютьюба, а сейчас ты этой бури часть…

Но пока ты вместе с народом твоей страны

полууставший полуозлобленный полунищающий полуголодный

но еще не уставший не озлобленный не обнищавший и не голодный

сидишь дома и смотришь как народы разных стран

в том числе очень близких, но таких сейчас далеких стран

выходят на улицы

и в бесконечном треморе обезболивающего дурмана

ты наблюдаешь как на улицу выходят народы твоей страны

твоего города

твоего района

твоей улицы

твоего дома

ой

смотри

не ты ли это

идешь внутри одной из колонн

не твой ли это смешной помпон

не твои ли щеки зарделись

не из твоей ли слабой глотки разносится крик

растворяясь (или умножаясь?) в общем гуле

неужели твой век созрел для идеалов

и ты тот самый гражданин грядущих поколений?

что ты сейчас чувствуешь?

(впрочем, можешь не отвечать)

здравствуй

элементарная

единица

политической

жизни