On Memory Landscapes

Bialowieza (or just “pushcha” as we usually call it in Belarusian) is one of the last and largest remaining parts of the immense primeval forests that once took the area of the entire European Plain. Its 94% are located at the territory of Belarus with the area of 40% of the county’s lands covered by forests. More than half of Bialowieza trees are above 100 years old, which means that more than half of them witnessed mass killings committed by first the Soviets and then by the Nazis and stood in silence surrounding hundreds of concentration and labor camps.

When thinking about what those forests were exposed to and what then remained in the “memory” of their thick bark, mighty branches, and the dense network of roots invisible from the ground, I cannot but get back to the endless debate on the definition of memory. In which way does it work? Who (or what) possesses the ability of forming and storing recollections? If nature can remember, what is it that we, humans, can learn from and about it?

Italian philosopher Umberto Eco identified three types of memory — organic, mineral, and vegetal. The first is made of flesh and blood and administered by our brain, transmitted through oral-based sharing practices, i.e. storytelling, from generation to generation. The second — mineral — is represented by various media used for information documentation: from clay tablets and monuments to mobile devices with their silicone digital storages, so good at doing our own natural job of recoding textual, visual, and audial data. And, finally, vegetal memory captured on pages of books, which at the dawn of civilization were made of papyruses. In this regard, demonstrating a certain romanticism, Eco celebrated libraries as temples of vegetal memory, calling them the most important way of keeping our collective wisdom.

Despite Eco’s beliefs in the superiority of vegetal memory over its other types due to the durability of books and other written records that allowed a 20-year-old young man to feel as if he had lived 5 000 years, the philosopher never actually spoke about vegetal memory tissue in its direct meaning — inherent to the very origin of the word. Books do remember, and so do monuments, but what about non-human agents that had existed ages before people and their ambitious desire to both remember and be remembered? Wouldn’t limiting the memory-keeping agency to people only mean getting stuck in the Anthropocene and ignoring the rather obvious truth of human’s secondary role in the world much larger than us?

In her article After Narrative: a Response to Brigit M.Kaiser and Kathrin Thiele, Australian cultural theorist Claire Colebrook doubts the appropriateness of Man is memory thesis and instead puts forward a different statement, To say that Man is memory is therefore not simply to say that all life exists by way of evolution, inscription, the sedimentation of past events and the opening to potential futures, but also that Man in the Western white supremacist sense has hijacked what might be thought of as human [P417]. What in this regard is needed is past reconfiguration by creating an archive that pays its debt to the past’s barbarisms and erasures which would mean the formation of a new ecumenical and planetary special-specific humanism where Man is highlighted as bound up with an earth and temporality not his own. [P418]

![A part of the installation "Parliament of Ghosts," by Ibrahim Mahama, exposed at Venice Biennale of Architecture, 2023. From the accompanying text: "The work originally addressed historical ideas around materials and issues of colonial exploitation […]. The space was inspired by both the residue of the Gold Coast Railway infrastructure and abandoned modernist buildings from the 1960s Nkrumah’s Volini in Tamale (Ghana). How do we restore memories to which access was denied? How do we excavate the past in order to build new futures?" Photo: Olga Bubich ©](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/Pzml3bIZONksd-k7SDd3OJfDvixKORp7J1q9O4RIBUM/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzg5ODFlYzEyMGQxZDczNzUxYTUzNDRlMTA1ZGNkYTU3OTYzNzY1NWEvc3RvcmUvODFhMGM3ZDRmN2E4YzY0N2Q4OWEwZWVkNGI1NDk0Mzc5OTA5NjQ0ZTlkMjVlODQ0NGE2YzQ5MzEwY2FhL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

So, if Umberto Eco saw libraries as temples for memory transition, conversion and conservation, half a century later, with the rise of neofascism, death of expertise and ignorance of planet’s heating, I would strongly stand for rethinking the classical ways we approach memory, memory bearers and memory keeping in general with an emphasis put on non-human agents — memory landscapes.

Yes, Man is memory, continues Claire Colebrook, but memory and the archive are possible only through the non-human — ranging from the lands and living beings that populate mythologies, to the planetary energies and matters through which humans have inscribed themselves as political. To this extent “Man” is unsustainable: the liberal individual of self-formation, autonomy and leisured reflection was only possible by way of a history of enslavement, colonization and energy appropriation that was never capable of being as universally inclusive and necessary as it pretended to be. [P418]

In order to openly challenge the Anthropocene and extend our concepts of memory preservation and transmission by adding to them non-human agents, we need to first research the role nature played in most devastating wars of the previous centuries (and, unfortunately, continues playing now), as a witness, hostage and victim of human interventions. And in this text, I would like to focus on nature in the context of the Nazi ideology and landscape cleansing plans of the occupied Eastern territories, including Belarus.

In our mind’s eye we are accustomed to think of the Holocaust as having no landscape, writes British historian Simon Schama in his paramount work Landscape and Memory dedicated to the research of the connections between these two phenomena. The first associations that one could have in this regard would probably be rather dark and gloomy — the nature that witnesses human suffering should be emptied of features and color, shrouded in night and fog, blanketed by perpetual winter, collapsed into shades of dawn and gray; the gray of smog, of ash, of pulverized bones, of quicklime. And thus it is shocking, as Schama remarks, to realize that many concentration camps actually belong to a brilliant vivid countryside with riverlands, picturesque lakes and avenues of poplar and aspen adorning their edges. [1995, P26] In the survivors’ memoirs, nature is often recalled as an element of existential paradox: yes, at times it was perceived as comforting and promising hope, but most often — as indifferent. Seasons will change and flowers will bloom regardless of people’s presence, or, as Belarusian scholar Inha Lindarenka writes, in woods the law of the forest operates, according to which nothing leaves, it just gets replaced.

The paradox we find between the essence of concentration camps and the natural beauty of their surroundings is actually not accidental and rooted in some of the central concepts of National Socialism — Dauerwald and Volk, in particular. The origin of the former is traced back to the late 19th century — standing for perpetual forest, it meant the introduction of sustainable practices that would ensure the long-term health and productivity of woods. Despite being a rather green positive practice per se, Dauerwald was in fact a red herring, a bright propaganda trope, of interest to the Nazis not so much because of the forests role in planet’s future, but as an element of Nazi thinking that legitimized elimination or enslavement of anyone non-German — Untermenschen (subhumans), a neologism applied to the residents of the occupied territories [P251].

So, the Nazis did love and even cared of nature, as long as they saw in it not only their property, but also one of the components of the newly imagined identity and a gracious justification of crimes. This thought had to do with the term Volk — an almost mythical faith in the goodness of the ethnically pure “common German” [P5] that penetrated all the aspects of German political, social, and intellectual life in the early 20th century. The dictum of the Nazi party called the German people to be kept strong and wholesome and one of the ways of achieving this aim was through the preservation of pure German traditions, monuments, and land.

In other words, Generalplan Ost was about bringing humans, nature and race into harmony in order to establish a new agrarian way of life for Aryan colonists. Here green and Nazi thinking came together to a degree not seen elsewhere. In order to achieve this vision, the landscape had to be made anew, first by forcibly removing the Slavic population, then by bulldozing away the past, and finally by moving Germans into the newly emptied space, [P13] note the authors of the introduction to the collection of articles provocatively entitled How Green Were the Nazis?

In October 1939 Heinrich Himmler, put in charge of the newly occupied territories, enthusiastically took up the mission of re-modelling them on the basis of the latest scientific research and plotting campaigns aimed at bringing revolutionary results guided. The intention was not to simply colonize the newly joined lands, but to radically change the landscape. [P13]

On the territories of Poland (defeated in September 1939) and western Belarus (occupied in 1941, then as a part of the USSR), it was also the wood that attracted the Nazis most, namely the above-mentioned Białowieża. According to the conceptual ideas reflected in the colonization program designed by a team led by SS Oberfuhrer Konrad Meyer, Professor of Agriculture at Berlin University, Białowieża was to be transformed into one of the Teutonic Heimat's national parks with its alien landscape first made into empty space and then — into something unmistakably German [P70-71] — Nazis' hunting grounds, agrarian lands, and Aryan towns.

Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn writes that, in fact, many German planners and architects were overjoyed by such an inspiring creative design opportunity to re-sculpt the Eastern territories in their totality, even it meant the suppression, exploitation, and extermination of the people who lived there. [P245] The researcher draws the example of Herman Koening, a famous German landscape architect, who envisioned the future of Eastern Europe mostly by applying the adverb instead. The dictatorial power of the victor will offer our generation the rare opportunity to operate artistically on totally new ground! he ambitiously wrote. Thus, for the Nazis, landscape care [P248] did not stand in paradox with their willingness to mercilessly murder those who lived in its vicinity. As the empire expanded to East, new order required new living spaces. And beautiful camouflaging explanations.

However, while descibing approximately the same period and lands but from a diferent perspective, in his volume Landscape and Memory Jewish history expert Simon Schama reminds that in practice alien territories re-modelling actually meant deportation of the Poles, along with Jews, towards further east, or else reducing the local (Belarusian) population to the status of barnyard animals that could be stabbed or slaughtered as the freshly reclaimed landscape required. [P70-71]

A German farmer is more fit for life, in the sense of having a higher calling, than a Polish baron, and every German worker possesses more creativity than the Polish intellectual elite. Four millennia of Germanic evolution point to an irrevocable chain of evidence, [P251-252] wrote Heinrich Friedrich Wiepking-Jürhensmann, a leading member of Himmler’s landscape planning board, in the article Aufgaben und Ziele deutcher Landschaftspolitik (Die Gartenkunst, 1940).

The domestication of the landscape in the occupied Belarus also stood for — apart from the enclosing the Jewish population into ghettoes for eventual liquidation — burning down entire villages, often together with their residents. Thousands of civilians—women, children, and the elderly—were burned to death inside the largest buildings in their villages, usually a barn, a school, or a church. In total, about 9 000 villages and more than one million houses were destroyed in the WWII around the country — the victory cost Belarus a quarter of its pre-war population, practically all its intellectual elite perished.

One of such destroyed villages was located just 60 kilometers from Minsk, the capital of Belarus. Its name was Khatyn — and the number of the people murdered in the peaceful surrounding of its pine and fur tree woods is known for sure. They were all locals — 156, half of them children. On March 22, 1943 a police battalion formed by the Nazis rounded them up, trapped in a shed, and set it on fire. Afterwards, the village was looted and burned to the ground. Only eight Belarusians miraculously survived, some — because they were covered by the dead bodies of their neighbors.

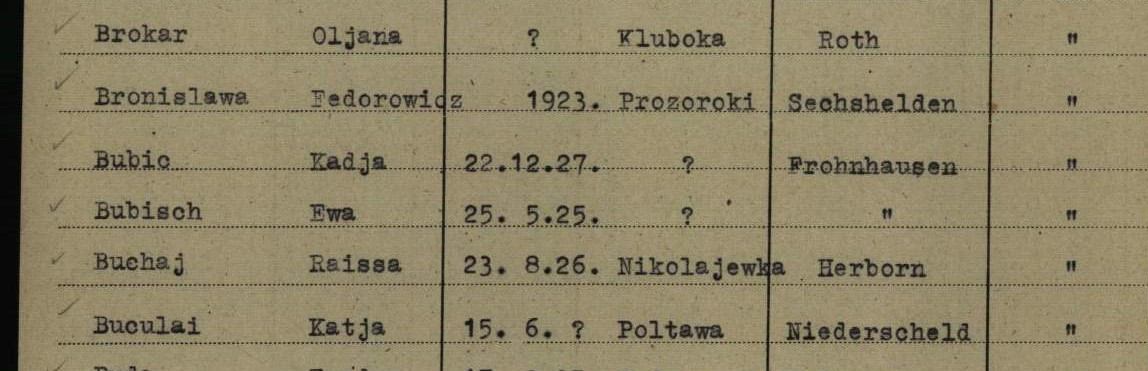

Over 80% of buildings and city infrastructure were demolished in the major towns of Minsk and Vitebsk. In Luban district alone — the area my father’s side of the family comes from — about 3,700 civilians were executed and more than 1,800 were deported to serve as forced laborers in Germany. One of them was my grandfather’s sister Ekaterina Bubich, or Kadja as she was misspelled in a Nazi insurance document I ran into while doing my routine search in Arolsen Archives. For almost a year, between May 5, 1944 and March 26, 1945, the 17-years-old girl was kept a slave worker — an ostarbeiterin - at Walter Krenzer Holzenwarenfabrik Frohnhausen — the experience she never talked or recalled later, when back to her native village.

According to its modern site, the factory in Dillenburg, west of Hesse, is actively operating and looks like a successful business. It still produces furniture made of wood. Upon contacting a local historian, I learnt that neither at the factory nor in the town, was the dark history of the plant’s use of slave labor mentioned.

Today, the vocabulary once used by National Socialist ideologists to speak about green nature thinking (Heimat, Landschaft, Heimatschutz, Naturschutz, etc) might sound neutral and even encouraging environmental protection, however the Nazis' ecological interests were in fact never coherent or unified and can rather be classified as populistic. Moreover, as John K.Roth fairly puts it, how can we doubt the fact that a full-fledged, global caring for the natural world would be utterly inconsistent with — indeed in determined opposition to — genocide and the destructive warfare that so often cloaks it? [P20]

From the very first stages of their regimes establishment, both the Nazis and Bolsheviks saw nature as something that could be instrumentalized — domesticated, consumed, cleaned or in any way altered for the perpetrators' physical or ideological needs. The normalсy of this approach was reflected, for example, in the praise the Soviets gave to the construction of a totally useless White Sea-Baltic Canal. Opened in 1933 with the original name of the Stalin Sea-Baltic Canal, it cost the lives of up to 25 000 laborers (all GULAG inmates) and irreparable nature damage. Poplar trees were planted in some concentration camps by the Nazis to serve as natural screens for the ashes thrown up by crematoriums, so human remains literally mixed with poplar seeds containing the potentiality of a future non-human memory bearer. Organic memory combined with a vegetal one. People became trees, trees become people. The same violent synthesis occurred with the soil of Auschwitz where human ashes were used as fertilizers or the waters of Ravensbrück those got thrown into.

Robert Smithson, a partner of the American artist Nancy Holt, once compared the strata of the Earth with a jumbled museum. And reflecting on this museum of the underground hidden strata in the thicket of Belarusian Kurapaty mass execution site near Minsk, or the Russian Sandarmokh with more than 6,000 victims identified by the activist Yuri Dmitirev (now in prison for 13 years due to his work, not welcomed by Putin’s regime), or Polish Sobibor afforested with new pine seedlings in 1943 by the Nazis to conceal the debris of the exploded crematorium, or the grass of Auschwitz lawns — all largely ignored in the writings on the Holocaust and other Nazi or Bolsheviks crimes — I have no doubts. Nature has memory and it actually performs a much better job in keeping and processing what it has been exposed to. People really become trees, and trees — wooden furniture * made by enslaved teenagers. But I do like Inha’s thesis about the law of the forest. Nothing leaves, it just gets replaced.

And probably it is not about landscapes only.

Berlin, 2023-2024

* After publishing this text, I received a message from a historian who, at distance, helps me look for more information on Ekaterina Bubich and Ostarbeiters in Dillenburg. He managed to get some additional facts about Walter Krenzer wooden goods factory she worked for in the Hessian State’s Archives in Wiesbaden.

From 1938 onward the company produced exclusively for the Wehrmacht, e.g. wooden caissons or some wooden parts for fighter jets in the Jägernotprogramm. That’s why they got "Ostarbeiter" for their factory. Unfortunately there is still few evidence regarding the concrete forms of accomodation etc. The company’s archive, as they told me, goes back only to the 1960s. But the owner, grandson of Walter Krenzer, knows from his mother, that there were barracks on the facilities, where the Zwangsarbeiter lived. Unfortunally there are no pictures from this time… he wrote.

Read more on The Art of (Not) Forgetting.