On philosophical methodology

Preface

Philosophy is a thought-in-progress. And when it is embodied in series of texts, at some point the previous texts begin to diverge from the subsequent ones. This creates the need to periodically correct previously published articles.

We live in situation of degradation of Russian culture, following the degradation of the Russian economy since 90's, which began in the 90s and continues to present days. Russian-speaking cultural space is collapsing. And this is a challenge for all Russian-speaking philosophers: does it make sense to continue thinking in Russian? I suggest that the Russian language, in terms of its structure, vocabulary and the number of books published in it, is one of the richest languages on our planet. And even in a situation of its decline, it can retain the potential of a means of preserving and developing culture in the post-Soviet space for many more decades.

But in the long term, it appears that English will retain its status as the language of international communication — as well as the language of global science. Therefore, today it is better for Russian-speaking philosophers and authors to move into the international cultural space and develop publications primarily in English than in Russian or other local languages.

Of course, becoming of a global culture is fraught with considerable difficulties. Struggle for the peaceful coexistence of different peoples requires the development of scientific, materialist and socialist philosophy. However, the ethico-political issues of reorganizing society on the principles of worldwide democratic socialism depend on the solution of methodological and general ontological problems.

First edition of this article was published in November 2021 under the title “On Philosophical Practice, Part 1” in the context of a discussion with dogmatic Marxists on the development of materialist philosophy.

In this translation and at the same time the second edition, I decided to omit a number of fragments related to the criticism of activism as a meaningless pseudo-practice and expand the fragments related to the description of the modes of operation of philosophical thought. The article also adds diagrams illustrating the levels of philosophical discourse. The introduction and conclusion elaborate on the functioning of philosophy in the context of assemblage materialism.

The change in the title of the article is due to the fact that the following articles, which reveal in more detail other aspects of philosophical practice, have deviated from the original plan and need even more processing. Whereas this article turned out to be a successful presentation of the foundations of philosophical methodology, and forms a semantic unity with the already published “Nomadology Manifesto” (RU, ENG) and “Assemblage concept” (RU), which will soon be translated. Today, these three texts are key to the understanding and further development of my philosophy, so they are translated in priority order.

Introduction

When examining the history of philosophy for a certain method, one cannot ignore the ancient and modern European dialectics, which, in general opinion, begins with Socrates and Descartes. Moreover, if the dialectic of Socrates (as presented by Plato) describes in the Timaeus three kinds of being as moments of the existence of a unite cosmos, then in Descartes the two substances, thinking and extended, are, on the contrary, isolated from each other, which requires the intervention of a philosophical god, ensuring the correspondence of the order of causes and effects how they occur in matter and how they are reflected in our thinking, which means the unity and knowability of the world.

Something else is important. For a century and a half, Marxists have been claiming that Marx, through critique, isolated the rational grain in Hegel’s texts — dialectics as a method, combined it with Feuerbachean materialism and applied it to the analysis of the contradictions of capitalism. This is partly true. However, to this day it is impossible to find an exhaustive presentation of the dialectical method in relation to science, philosophy or politics in handbooks on dialectical materialism. It is not found in the works of Marx himself.

The structuralist discoveries of the 20th century made it possible to discover the impersonal material structures of interaction that underlie various phenomena of social life. Whereas the beginning of these studies was laid in Marx’s Capital, which was correctly noted by its researcher Louis Althusser, who supplemented Marx’s implicit structuralism with the consciously verified structuralism of de Saussure and Lévi-Strauss.

Does philosophy, philosophical discourse, have a similar structure? I suppose yes. Factually, this structure is present in real philosophical works of thousands philosophers around the world, and has different aspects. But philosophical work as kind of verbal behavior are determines by social and cultural factors. Philosopher is a social position that determines his relation to other positions in the structure of labor division — and at the same time philosopher is a cultural position that depend from vocabulary of using language and its pragmatic operationing.

According Deleuzian meta-philosophy surface of connection of social and cultural assemblages is constituate a plane of consistency — battlefield of production and sublation of contradictions as productive causes of development of philosophical thought. Therefore two biases in philosophic work is possible: overrating or social, or cultural factors. In first case philosophers become thoughtless activists that can only serve to contingental societal demands. In second case philosophers become armchair scholars, divorced from real life. In both cases there in no invention of concepts that combine social actuality and cultural virtuality. It is a ways of desassembling of philosophic assemblage. Operational closureness of philosophy from social and cultural norms is condition of its implementation.

Another problem it is relation of philosophical and scientific knowing. According Deleuze’s idea, science is research of functive as an elements of functional relations in plane of reference. What is a difference between concepts and functives, plane of consistency and plane of reference? It is key problem to understanding possibility scientific philosophy, its distinction from metaphysical delusions.

Obviously, functives is a constants and variables in scientific equations that express some function that referenced to constant and variative data in experimental experience of our interaction with plurality of modes of material motion. For example, in equation F=mG, there is a three functives: F and m is variables that simbolized force that measeres in Newtons, m is massa measures in kilogramms, and G is gravitational constant whose value is approximately 6,674×10−11 N⋅m2/kg2. And the whole equation are reflect regularity in motion of bodies by the gravity force. Scientific research of functions that rule the different modes of motion of matter covers totality of all possible and conceivable appearances. This fact of independence of science from philosophy was a reason of emergence of mechanists movement in early soviet materialism. Mechanists denied necessity of independent philosophy and proclaim reduction all philosophical theories and conceptions to verificational scientific observations or to unobservated metaphysical fantasies.

Mechanists interpretation of interrelation of science and philosophy didn’t take into consideration that any strata or assembled multiplicity of material objects that moved and existed by certain set of regularities and describes in plane of reference in scientific terms are limited from other stratas that surround this one in space from all directions. And surfaces of connection of different stratas that sublates specifications of each other is constitute the same plane of consistency that is universal background of any stratas. For example, correct scientific notion of matter is equivalent to contemporary presentations about substrate of discovered functions. Philosophical concept of matter is universal substrate of all possible discovered and undiscovered functions in any concrete sciences from physics to linguistics. Incorrect notion of matter is identification of matter and stuff that have mass with distinguishing of matter and field, energy, information, consciousness and many other entities. In this way set of stuff and field is remains ungeneralized, and energy, information, consciousness, laws of nature etc suggested as unsubstrative independent entities — that is direct way to idealism and theology. In addition, existing ideas about functives and their substrate are identified with reality-in-itself, which is a gross methodological error, refuted by the progressive progress of scientific knowledge, which sublates or refutes previous ideas about the nature of reality. It is an example of inconsistent reference: identification of stuff and matter leads to deformed system of cognition where functives set that reflect properties of reality according to completed observations does not suggest conceptual level of its generalization for extension and change model in the next stage researches.

Now we can distinctialize difference between scientific functives and philosophical concepts.

As previously was remarked, scientific functives is a constants and variables in scientific equations that express some function that referenced to constant and variative data in experimental experience of our interaction with plurality of modes of material motion

Scientific concepts is significations of consistency of different parts, levels and states of reference systems that reflect universals of objective background that allow material substance to produce its modes and its regularities.

So we can note difference between subjective and objective functions and subjective and objective consistency as kinds of thing-for-us and thing-in-itself: subjective functions it is equations that produces in scientific practice; objective functions is regularities of moving matter itself; subjective consistency is adequate correlation of different parts of our theories about nature of reality; objective consistency is universal property of Nature as a substance that produce its modes and sublates contradictions of its coexistence. In other word, subjective consistency is solution of contradictions of our theories, objective consistency is sublation of contradictions of reality itself.

Philosophy in this prospect is area of generalized consistency that based on particular consistencies of concrete areas of activity — science, politics and art — that have own specific rules of implementation: reference for science, power for politics, expression for art. Let’s count meanings of this characteristics for consistency and vice versa:

In science: consistency of functives means that they express sublation of contradictions in objective reality and in its scientific description.

Reference of scientific concepts means that all concepts that used in scientific description are express existence and properties of real assemblages, not our subjective fictions about world.

In politics: consistency of political slogans means that they express sublation of contradictions in social modality and its political solution.

Power of political concepts means that they has performative power of political decisions or slogans as incorporeal transformations of regime of moving of things-in-system.

In art: consistency of artistic perceptions means that they express sublation of contradictions in neutral spatiotemporal and affective sense, beyond problematic of scientific reference or political influence.

Expressiveness of artistic concepts means that they can restart work of imaginary to present sublation of contradictions immediately, on the level of first signal system.

In philosophy scientific, political and artistic concepts together its exoconsistencies are generalize by line of transversal or cross-section in state of endoconsistency — sublation of differences and contradictions between particular concepts and its consistencies.

This distinction and connection of four types|groups of assemblages can be proved next way. Independence of philosophy from science is consequence of infinity of Nature, innumerable plurality of modes of material motion — and our limited capacity to observe it. The same is true for politics and art. Each assemblage has his own specifications but philosophic conceptualization constituate framework for interdisciplinary studies and practices. So structure become a method. From description to prescription — it is the way of development of philosophic thought.

1. Philosophical methodology of Rene Descartes: dialectics of clear and distinct

The advantage of Descartes' dialectics is that it reflects the methodology. In addition to the very sensible “Rules for Guiding the Mind,” which should have been outlined and schematized long ago, in “Discourse on the Method” he gives a shorter version of the method:

" 1. The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.

2. The second, to divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.

3. The third, to conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex; assigning in thought a certain order even to those objects which in their own nature do not stand in a relation of antecedence and sequence.

4. And the last, in every case to make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted."

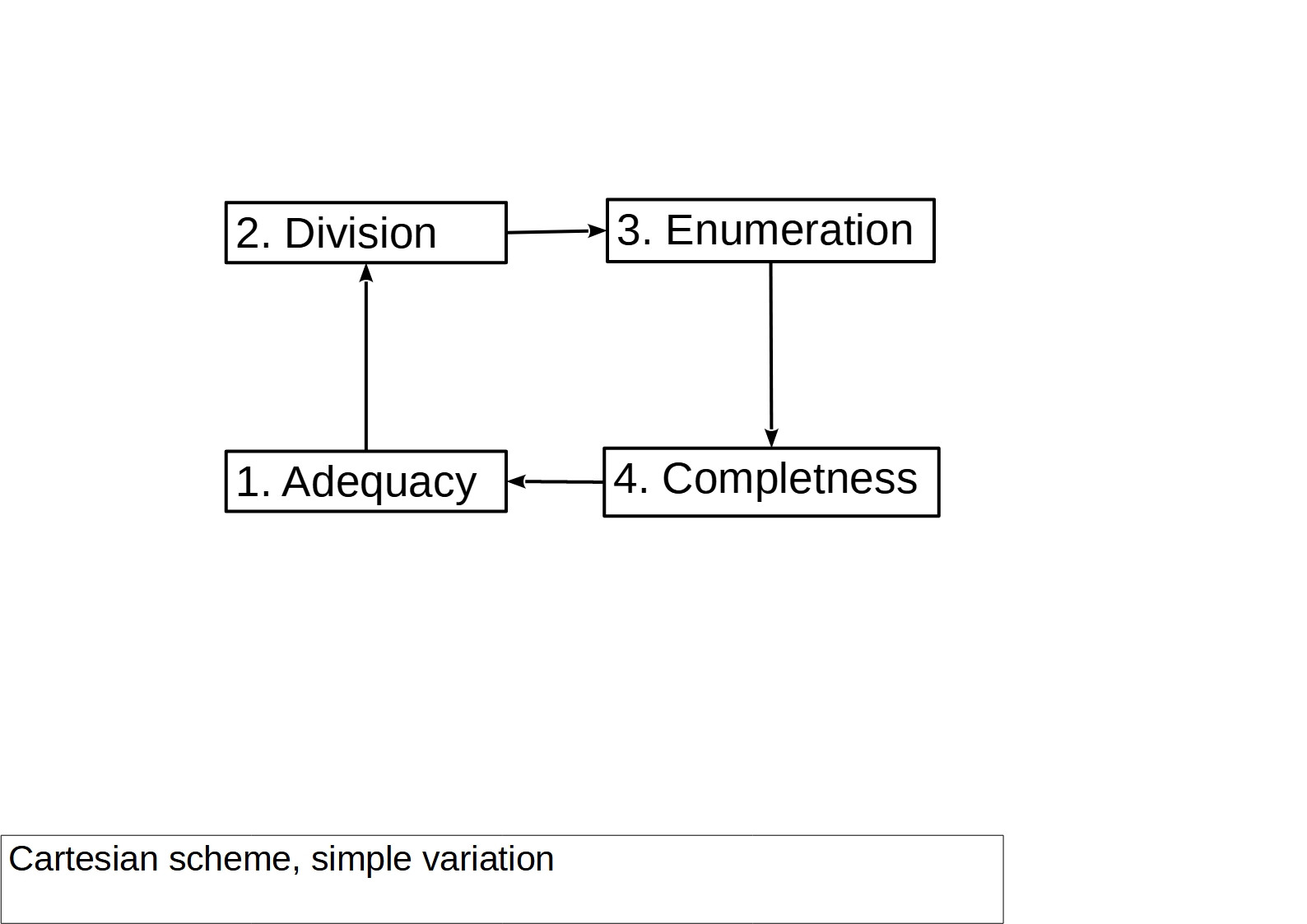

In other words, Descartes writes that (1) only what is clear and distinct should be accepted as true; (2) divide complex problems into parts; (3) progress in considering problems from simple to complex; (4) record the results of the review in the form of exhaustive lists.

For brevity, these principles can be designated as the principles of adequacy, divisibility, enumeration and completeness:

Michel Foucault’s books "Words and Things" and "The Archeology of Knowledge" give an interesting study of how these principles arose in the 17th century, what preceded them, and how they developed to their modern state. At the same time, he acknowledges the presence of qualitative leaps in the evolution of knowledge production structures, but does not indicate the exact reasons for these transitions, a shortcoming of his research that was already noted by early critics.

In this context, I am interested in a more specific point related to the dialectic of the principle of adequacy, within which two criteria are distinguished: clarity and distinctness. More precisely, the distinction between clarity and distinctness as philosophical principles and the extra-philosophical requirement of simplicity and intelligibility, which, as I understand it, has obvious metaphysical assumptions that are not permissible in philosophy.

In order to simplify something, it must first be complicated — without complication there will be no concrete simplicity, but only ideological abstractions of “common sense”.

Let us therefore first consider the meaning and relationship of the concepts of clear and distinct as philosophical criteria in motion, and then compare the results with the requirement of simplicity and intelligibility.

First of all, the concepts of clear and distinct can be understood as synonyms. At the same time, their meaning, taken by themselves, is not very clear and distinct: if we are talking about understanding, then what is understanding in general, how does it relate to the concept of meaning, truth, adequacy, etc. The use of two terms allows us to distinguish two meanings of understanding: clear as understandable in itself — and distinct as understandable in comparison with another. In this case, we can introduce a couple of terms that characterize two modes of the incomprehensible: dark as incomprehensible in itself — and foggy as incomprehensible in comparison with another.

Next, let’s consider whether these terms are consistent with themselves, or are they characterized by some contradictions?

As an example of a clear, understandable object in itself, let’s take a delicious pie standing on the table: it is absolutely clear that no matter how much you look at it, your mouth will not become sweeter. Therefore, it is clear that the pie should be eaten rather than looked at, which, by the way, is one of the theoretical provisions of Marxism — it was not for nothing that Engels wrote in the introduction to the English edition of “The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science” that “The proof of the pudding is in the eating” (CW, vol. 22, p. 303). However, this distinction lies to a greater extent not so much between contemplative and activity-based materialism, but rather between contemplative and consumerism. For in order to eat the pudding, it must first be made; otherwise there will be nothing to contemplate or eat.

It is clear from this that such clarity is deceptive. No matter how many puddings we eat, it is unlikely that we will be able to find out how to prepare them based on this. It is impossible to learn from a clear feeling of hunger its physiological causes and the mechanism of digestion. The same is true of all things that appear to ordinary consciousness as clear and understandable in themselves: upon careful examination, they turn out to be dark and incomprehensible, and the clearer a thing immediately appears initially, the darker it appears in comparison with itself. As an extreme example, we can take the category of being, the clarity and darkness of which, from Parmenides to Heidegger, stimulated philosophical thought to the most persistent work.

At the same time, as we consider, we move from one term, identical to itself and different from itself as clear and dark, to a clear difference between these two terms. It is clear that the difference between clear and dark is distinct; but is the difference between the clear and the distinct itself distinct? To answer this question, let us compare the course of reasoning with the original Cartesian principles: adequacy, divisibility, enumeration and completeness.

Clarity as a criterion seems to fully correspond to the principle of divisibility, since upon examination it is divided into the clear itself and the dark as its reverse side. The transition from clarity and darkness to distinctness also satisfies the principle of enumeration, since in it we ascend from simple to complex. In this case, the next step in the dialectic of criteria must correspond to a general set of principles.

Distinct as an understanding of meaning by contrast, in comparison, presupposes the multiplication of a number of compared things. However, then more comparisons we make, that more foggy and mysterious the subject matter becomes. Thus, the criterion of distinctivity also turns out to be contradictory: the greater distinctivity we achieve by multiplying comparisons, the more vague and incomprehensible the subject under consideration becomes. This is especially noticeable in the social sciences: as the research parameters become more detailed, the concept of the psyche for psychology, politics in political science and society in sociology becomes so vague that from the hundreds of proposed concepts it is often impossible to draw any definite conclusion even about whether such a subject exists, as a psyche, society or politics, not to mention what it referenced.

At the same time, just as the darkening of the clear provides a transition to the distinct, the fogging of an object can provide a transition to its clear representation in the case of highlighting the essential and darkening the unimportant distinctions from the set of differences achieved by the movement of distinctialization. Thus, we have four concepts and four semantic movements: clarification, obscuration, distinctialization and fogging, corresponding to four methodological principles and forming a cycle.

The history of philosophy convinces us that such a cycle exists both in theory and in practice. Thus, ancient dialectics, begun by Socrates, became more complicated in Plato and was cataloged in Aristotle, who wrote a lot of treatises on a variety of issues of contemporary knowledge. Later, in late antiquity and in medieval scholasticism, Aristotle became the subject of interpretation and interpretation upon interpretation, so that the system of interpretation, highlighting ever new differences in the movement towards unattainable completeness, becomes so vague and abstract that it creates the conditions for a rupture and transition to a new clarity mediated by the previous cycle. This is what we find in Descartes, whose ideas follow the same path of development among his French and German followers, who develop on their basis the Encyclopedia and a number of systems that make up the stage of German classical philosophy. At the same time, the Encyclopedia of Enlightenment entails the same break in the direction of simplicity and clarity in the person of Jean-Jacques Rousseau; just as German idealism, especially Hegelian, causes a whole series of ruptures: Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, Feuerbach and Marx with Engels, not to mention Young Hegelianism, neo-Kantianism and positivism.

In short, there is a theoretically demonstrable and empirically observable tendency in which philosophical systems, taken in motion, describe cycles of complexity and simplification in which understanding not only increases, but also decreases. Thus, the moments of philosophy are not only knowledge and understanding, but also ignorance and misunderstanding, so that the volume of both increases cumulatively. Which, by the way, repeats the Hegelian dialectic of being-for-itself. Which those comrades who, instead of studying the “Science of Logic” do not do this on the grounds that a well-known vulgarizer of Marxism and dialectics strongly recommends carefully studying Hegel, clearly do not know — and therefore will not be able to apply it to comprehend philosophy in motion, which movement excludes fixation on simplicity and clarity alone, which is preached by that bourgeois marketer.

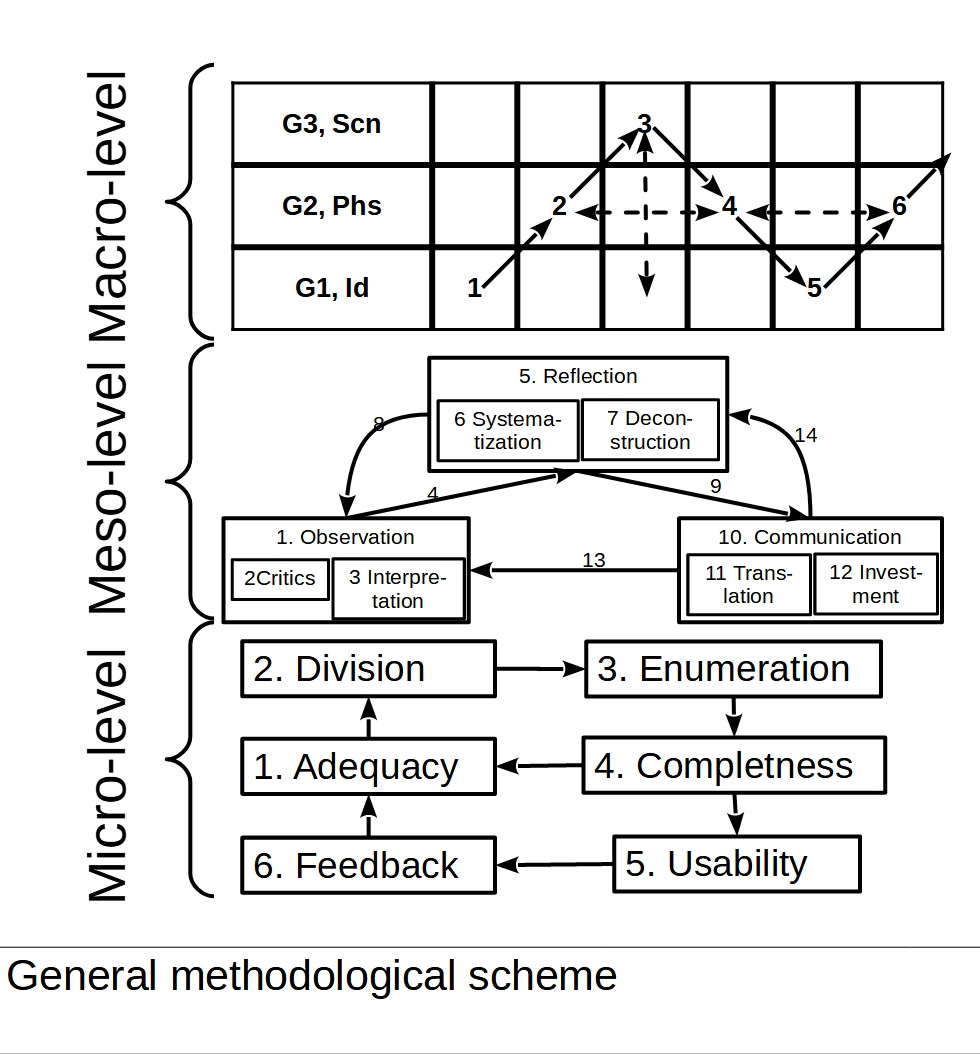

If Descartes describes the movement of philosophical method at the micro level, then Gilles Deleuze in “What is Philosophy?” and Louis Althusser in "For Marx!" are describes it at the meso and macro levels, respectively.

2. Philosophical methodology of Gilles Deleuze: dialectics of the concept

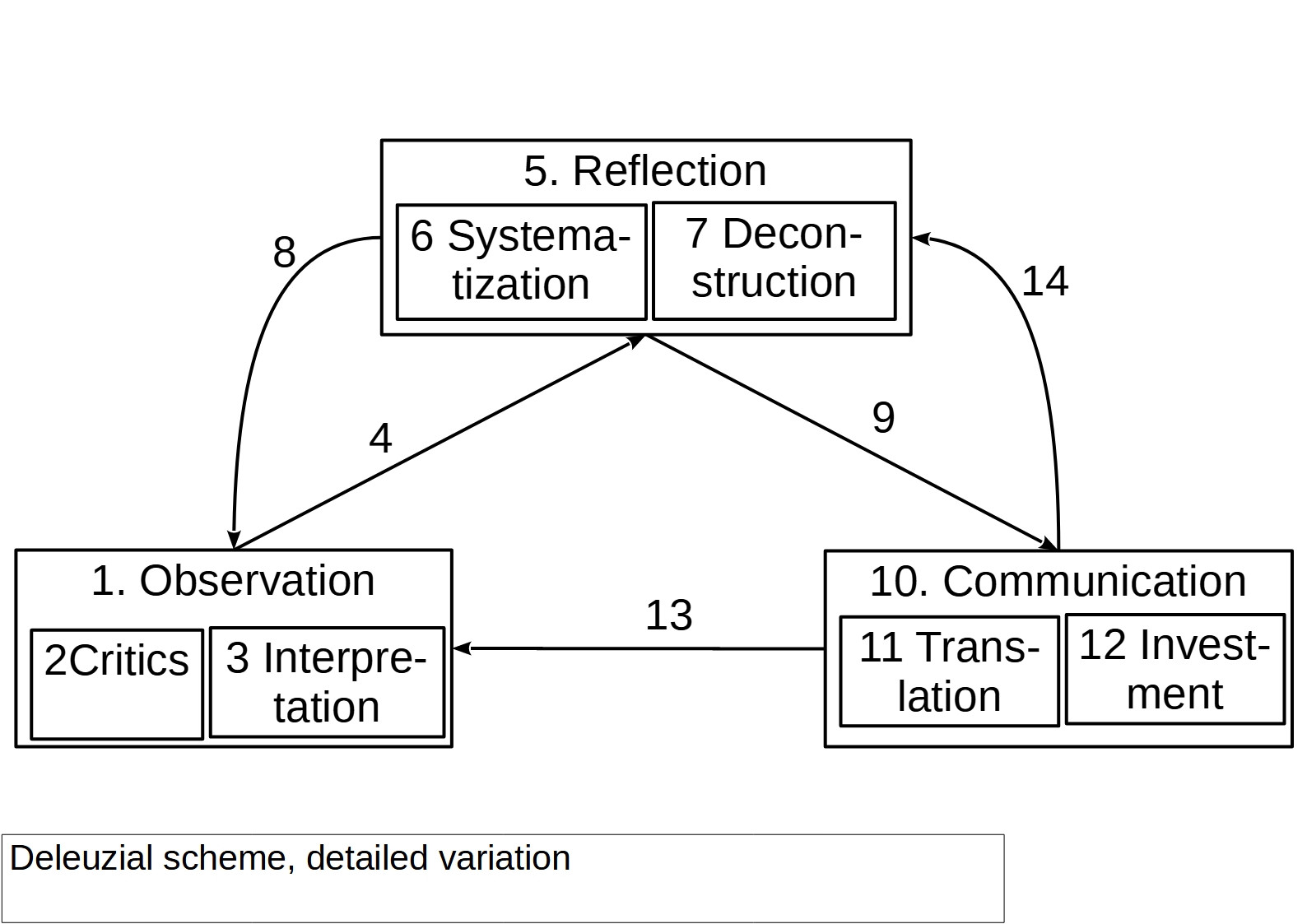

Gilles Deleuze in “What is Philosophy?” defines the latter as the creativity or invention of concepts, distinct from the three areas of their application: observation, reflection and communication. This is generally true, since the unit of objectification of philosophical meaning is a concept, concept, category, existential — in a word, a specially designated term, which, as we know, differs from vague ideological ideas, and from scientific functives, and from artistic percepts, and from political slogans — since these subsystems of social life differ from each other. In other words, we can say that a concept is a way of demanding and using meanings.

Accordingly, if we want to engage in philosophy, then we are faced with the task of coming up with new concepts that are useful for philosophy itself and other subsystems of society associated with it. Why do you need to solve two interrelated problems:

Firstly, decide on a set of existing concepts, so as not to invent something that has already been invented by someone, long ago or recently — that is, make a list of them in order from simple to complex;

Secondly, to explore which concepts are used and how in the three areas mentioned by Deleuze: in observation, in reflection and in communication.

In the April report “Philosophy as Practice: Observation, Reflection, Communication” I outlined ways to solve the second problem; and as for the first, the beginning of its solution is the article “On materialistic categorization” (RU) which I already sent you, and which, in the course of writing, was divided into three parts, and it will be good if the remaining two do not multiply further.

What are observation, reflection and communication from the point of view of systems theory? This concepts may be define and schematize the next way:

Observation is an elementary unit of thought-activity, consisting in distinguishing one thing from another. It is to observations that Descartes' criteria and principles relate: every difference must be adequate, that is, clear and distinct due to its divisibility, that is, distinguishability. The set of observations should be arranged in order from simple to complex, achieving as much completeness as possible. Derived from observation are regimes of criticism and interpretation, in which sets of observations are observed, which are any texts. They can be given the following definitions:

Critique is the observation of a certain set of observations with an attitude towards its falsity, but productivity.

Interpretation is the observation of a certain set of observations with an attitude towards its truth, but incompleteness.

While observation itself can also be defined as the discrimination of opposites in motion, since one or another opposite is always distinguished in one or another relation, which is never stationary.

Reflection is a philosophical operation of the second level, since the subject of reflection is not a comparison of individual observations, but ways of comparing them. A classic example of elementary reflection is, again, the Cartesian Cogito, self-thinking thinking. Types of reflection are systematization and deconstruction, which can be defined as follows:

Systematization is a comparison of comparison methods in which they form an integral semantic system.

Deconstruction is a comparison of methods in which they disassemble a semantic system into its components.

About this dimension of Deleuzian philosophy there is a recent book by Andrew Culp, “Dark Deleuze,” in which he distinguishes between the traditional, “joyful” understanding of Deleuzian methodology, to create concepts — and its dialectical opposite, to destroy worlds as meaning systems. In Marxism, however, this idea has long been known — just remember that Marx wrote about the weapon of criticism and so on.

Communication — the comparison of one’s own and others' methods of communication, reflection and observation, is a state of socialization of philosophy, its openness to the outside — which, nevertheless, relies on the removal of isolation and delimitation from any social prejudices. In other words, the reasons why a philosopher can enter into communication have nothing to do with social requirements — otherwise we are not dealing with a philosopher, but a sophist or something worse. Special types of communication are broadcast and investment, which can be defined as follows:

Translation is the transfer of norms of philosophical observation, reflection and communication within the framework of philosophy itself for the next generation of its bearers.

Investment is the transfer of the products of philosophical observation, reflection and communication beyond the boundaries of philosophy to representatives of other subsystems of society.

Based on the above, it is clear that a philosopher is not only a constructor, but also a deconstructor of semantic systems; and concepts are verbal tools for transforming meanings. From here comes the difference between sense and nonsense as marked and unmarked space, which for the three regimes acquires the meaning of unobservable, unthinkable and ineffable. Deleuze wrote more about the dialectic of sense and nonsense in “The Logic of Sense,” although in my opinion it is somewhat vague.

We can say this more simply: in order to comprehend actual processes, it is necessary to uncomprehend the space of their movement; in order to distinguish something, it is necessary to un-distinguish everything else. In this case, any error in thinking are reduced to either a failure to distinguish what is essential, or to distinguish between the inessential (or even the non-existent), or to a combination of both.

From here follows a materialist interpretation of Kant’s ideas about the transcendental subject, the structures of distinction and non-distinction of which are socially constructed. And the Marxist criticism of opportunism can be understood as the identification and elimination of such errors for the political subject, which I wrote about in “Classification of Opportunisms” (RU). Thus, populism as a type of right-wing opportunism consists of an excessive discrimination of momentary fluctuations in the mood of the masses — and, accordingly, a failure to distinguish between objective tendencies that determine both the fluctuations and the general course of the process. On the contrary, sectarianism as a type of left opportunism consists of insufficient differentiation of current political processes and isolation into oneself. Moreover, both extremes are defined through a gap (remember Heidegger and the phenomenology of human gestalt), in one case insufficient, in the other excessive.

The classics of Marxism wrote quite unequivocally about the close spiritual connection of opportunism with idealism and metaphysics. Thus, Lenin in “Materialism and Empirio-Criticism” writes the following: “That the “scientific priesthood” of idealistic philosophy is a simple threshold of direct priesthood, there was not even a shadow of doubt about this for I. Dietzgen. “ Scientific priesthood,” he wrote, “seriously strives to assist religious priesthood .” “In particular, the area of the theory of knowledge, the misunderstanding of the human spirit, is such a lousy pit” (Lausgrube), in which both clericalism “lays its eggs.” “Certified lackeys with speeches about “ideal goods”, dumbing down the people with the help of tortured (geschraubter) idealism,” — this is what professors of philosophy are for J. Dietzgen. “Just as the god’s antipode is the devil, for the priestly professor (Kathederpfaffen) is a materialist.” The theory of knowledge of materialism is “a universal weapon against religious faith,” and not only against “the well-known, real, ordinary religion of priests, but also against the purified, sublime professorial religion of intoxicated (benebelter) idealists.”

How should the concept of tortured be defined in this context? In essence, it turns out that tortured idealism is idealism achieved through intense, painful efforts to distort clear and long-proven scientific and philosophical positions — and at the same time, fruitless and meaningless efforts, since they contradict the objective trends of social life, daily refuting and overturning idealism. In other words, exhaustion is the result of intense efforts to achieve a goal, which both external and internal circumstances hinder. Opportunism can then be defined as adaptation to forced tendencies.

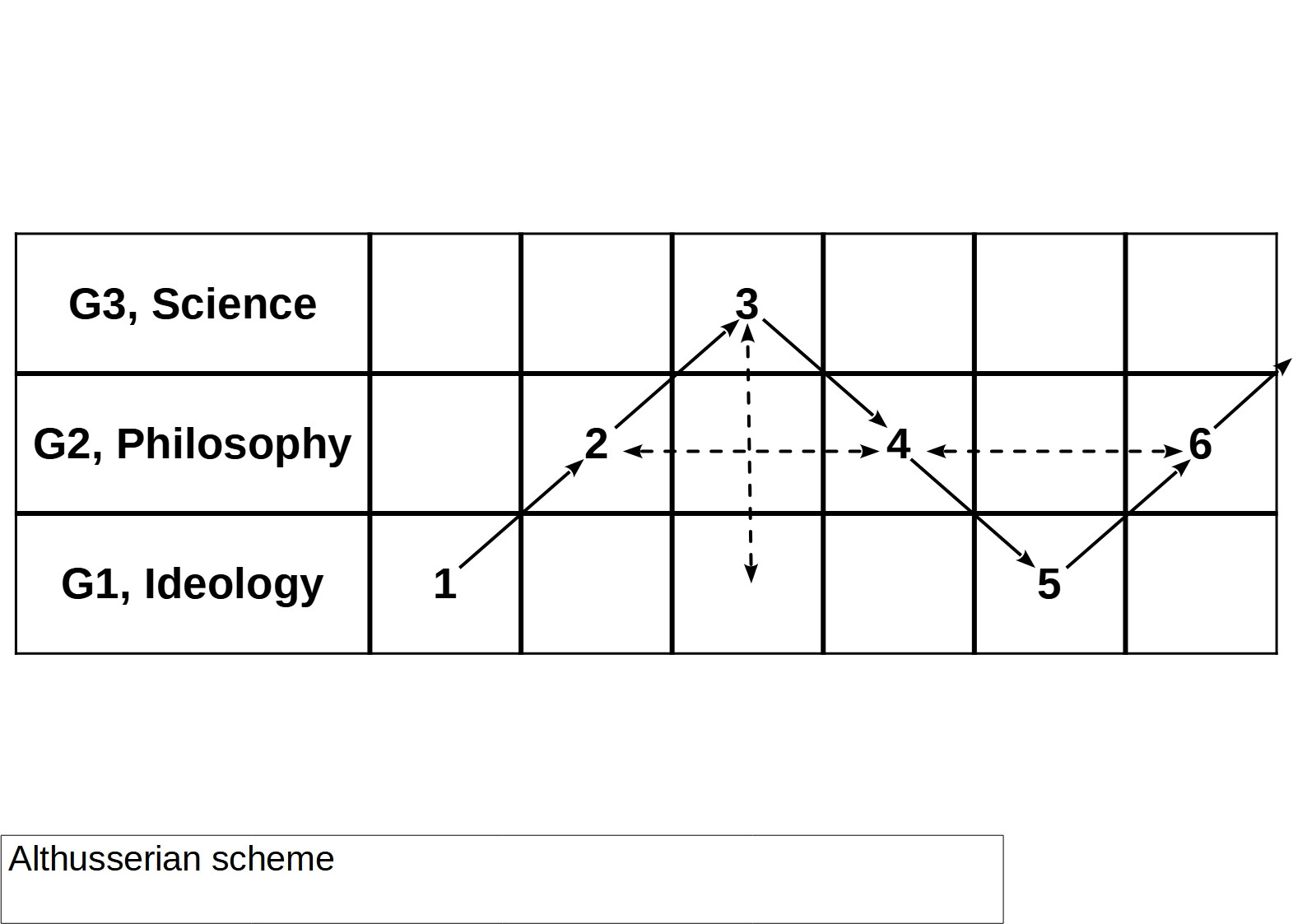

3. Philosophical methodology of Louis Althusser: dialectics of transition through the Generalities

The question of defining capitalism is one of the most relevant for modern politics, political philosophy and socio-historical science, not only in itself, but also as a link in the transition between Generalities. The concept of community was developed by Louis Althusser during the deconstruction of Marx’s dialectical method. In total, Althusser identifies three Generalities based on Marx’s texts — ideology, philosophy and science, distinguishing without giving them an unambiguous definition. As a first approximation, we will accept the definition of community as ways of distinguishing, inferring and transforming a set of ideological, philosophical or scientific statements. At the same time, science and ideology as Generalities differ as adequate and inadequate ways of distinguishing the world, respectively, while philosophy plays the role of an intermediate link, normally transforming ideological ideas into scientific concepts, as Althusser interprets it in the collection “For Marx!” .

At the same time, this trajectory of transition between Generalities from the point of view of Marxism, the provisions of which was developed by Althusser, is partial. Thus, Marx, in addition to the famous 11th Thesis on Feuerbach, which states that “Philosophers have only explained the world in various ways, but the point is to change it,” in the preface “To the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” notes both the insufficiency of the weapons of criticism and and its relationship with its chiasm, which plays the role of Derridean replenishment. Lenin writes about the same thing in his “Philosophical Notebooks,” outlining the trajectory of transition between Generalities not as an ascending vector, but as an arc of ascent and descent: “From living contemplation to abstract thinking and from it to practice — such is the dialectical path of cognition of truth, cognition of objective reality."

Thus, in the works of Marx, a certain logic of transition can be traced between positions and their corresponding problematics: at an early stage, he, together with Engels, wrote philosophical texts criticizing bourgeois ideology — but then they moved on to the scientific study of the capitalist mode of production, its laws, and from there — to political practice of its transformation.

At the same time, it cannot be said that this transition trajectory unfolded strictly in stages. Rather, it unfolds synchronously at the moment of the epistemological break between the young Marx, a humanist, a Young Hegelian and a Feuerbachian, and the mature Marx, who in Althusser’s retrospective interpretation switched to the point of view of theoretical anti-humanism. In this case, the transition between positions in an already developed structure would be specified in different periods of time with different probabilities, arising from the combination of social conjuncture, the logic of the development of the texts themselves and physiological factors operating in the author’s body and his environment (and how can one not recall the poetic thought here? Camus that maybe, in the end, “it’s all the Sun’s fault!”).

In addition, there is a pattern according to which the moments of ascent and descent between Generalities are distributed among various figures, so that gaps between mental activity positions correspond to gaps between historical periods, countries and characters. Thus, if the work of Marx and Engels was aimed primarily at criticizing bourgeois ideologies, creating a scientific theory of capitalism as a formation and as a method of production, and only lastly at disseminating their views, then the work of V. I. Lenin and L. D. Trotsky was aimed at adapting theoretical conclusions to the tasks of the social revolution in Russia, at making a distinction with purely critical and theoretical philosophy, as well as at reflecting on the achievements and mistakes of the social revolution.

Similar transitions can be identified for many major revolutionary processes associated with the establishment of new formations in the conditions of existing philosophy and scientific knowledge (it is clear that for a clan-tribal system with its undeveloped Generalities and totality of ideology, this scheme hardly makes sense). Thus, the chain of socio-noematic switching, launched by Descartes at the moment of radical doubt, constituting the cogito as a reflexive self-justification, leads through the encyclopedism of the Enlightenment to expropriation and the guillotine for the enemies of rising capitalism and bourgeois democracy.

With this in mind, Althusser’s concept can be schematized as follows:

This scheme is a significant simplification, since it does not take into account the previous series of breaks, already present in a removed form at the moment of transition between positions 1-2, that is, the epistemological break made by the young Marx in relation to the first position — bourgeois = humanistic (and, as it later turns out, oedipal) ideology. Thus, the following positions, breaks and transitions take place using the example of the development of Marxism from its emergence to reflection on the results of the October Revolution:

Gap G1-G3 is between Generalities of ideology and science, constitutive for the entire space of Generalities;

Position 1 — bourgeois ideology with inclusions of religious and magical survivals (texts by Feuerbach and early works of Marx, including the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844);

Transition 1-2 — criticism of bourgeois and all previous ideologies;

Position 2 — philosophical understanding of social contradictions that are the reason for the existence of ideologies, development of concepts adequate for scientific research (works of the gap — German Ideology and Theses on Feuerbach);

Transition 2-3 is a way out of philosophical reflection to the scientific study of reality itself with the help of previously developed concepts;

Position 3 — scientific study of reality (Economic manuscripts of 1857, Capital 1, 2, 3 volumes);

Transition 3-4 — adaptation of scientific conclusions about the structure and possible ways of transforming reality to political philosophy (K. Kautsky “The Economic Teachings of Karl Marx”, “The Path to Power”; V.I. Lenin “The Development of Capitalism in Russia”, “Imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism");

Position 4 — political reflection on scientific conclusions and the possibilities of their application (V.I. Lenin “What to do?”, “State and Revolution”);

Gap 4-2 — demarcation of political and critical-theoretical philosophical positions in the structure of the transition between Generalities (V.I. Lenin “Materialism and Empirio-Criticism”);

Transition 4-5 — exit from political philosophy to the practice of political struggle;

Position 5 — the practice of transforming society (the event of the October Revolution of 1917 and its subsequent development);

Transition 5-6 — exit from the revolutionary practice of transforming reality to reflection on its results;

Position 6 — philosophical reflection on the results of the October Revolution (the works of L.D. Trotsky “Permanent Revolution” and “Betrayed Revolution”; but also the Neo-Marxist works of A. Gramsci, D. Lukacs and M. Lifshitz, W. Reich and the entire Frankfurt School).

In terms of system theory, the first five positions themselves can be characterized as primary differentiation associated with the establishment of basic distinctions, while the sixth, Neo-Marxist position represents the reflexive introduction of differentiation back into the differentiated — that is, the application of the methods of dialectical and historical materialism to themselves.

It is clear that the presented fragment of the space of Generalities is incomplete, and it itself extends far back and forth — relatively speaking, from shamanism to schizoanalysis.

Nevertheless, it gives a clear understanding of both the multi-positionality that is initially inherent in Marxism and therefore, in the course of its follow-up, excluding the possibility of any kind of dogmatism, and the place of the question of the definition of capitalism, which is located in a position equivalent to transition 2-3 and presupposes a transition in a removed form, equivalent to transition 1-2, in which, taking into account previous philosophical and scientific achievements, the humanistic interpretation of society is excluded.

Conclusions

So, we have line of observations of three levels of the philosophy assemblage that can be schematized next way:

This is the way that adequate concepts are producing, distributing and consumptions. What’s about inadequate?

Previously we noted that reference, influence and expression is investmental criteria of conceptual consistency, whose conditions is connectedness of philosophy with material production, experimental science, mass revolutionary politics and progressive art. On the contrary, unreferenced concepts are produced in conditions of abstraction of intellectual labour from other social practices and acquire the ideological function of misleading the subjects of the exploited class. Ideological state apparatuses works with unreferenced metaphysical concepts to delude the people. The same true for metaphysics in politics and art — inconsistent concepts is needed to ruling class to degrade capacities to cognition, influence and sense the world in masses. In other words to reduce their revolutionary potential.

So, we can distinguish concepts and philosophical divisions that support or not support consistency of philosophy itself. This reflective relation of philosophy to itself is key criterium for outdifferentiation of philosophy from ideological apparatuses and ideological pseudophilosophy.

In this prospect we can breake false and ideologically contaminated relation of some contemporary “marxists” to religion and other kinds of delusion. When S. Zizek writes book “Christian atheism. How to be real a materialist”, where he appeal to christian theology in the prospect of Singularity — and other “marxists” quotes his book as model for philosophizing, we should quotes reasoning of another author as an example of immediate relation of the materialism to ideological philosophies to show stricktly incompatibility of our and they standpoints:

“- Here it is (method against christian ideology and theology), said the count, it is violent, but it is sure: we must arrest and massacre all their priests in a single day… treat all their followers in the same way, destroy at the same minute even the slightest vestige of Catholic worship… proclaiming systems of atheism; immediately entrust the education of youth to philosophers; multiply, give, spread, display writings that propagate unbelief, and severely impose, for half a century, the death penalty against any individual who reestablishes the chimera (of christianity). (If we compare the floods of blood that these scoundrels have caused to flow for eighteen centuries, with those that would be shed by the means indicated by Belmor, and we will see that it is far from that the means let him be violent as he says: he is only just, and it will only be after his execution that peace will reign among men.)”

As already mentioned, this Sade’s passage expresses the immediate relation of materialist philosophy to christian ideology and theology as forms of false consciousness. And since the truth of materialism and the falsity of religion have long been proven, and practical philosophy is outdifferentiated from ideological prejudices by critical philosophy and scientific knowing of the world, then critique of the struggle against ideologies through the physical destruction of all their carriers can only be criticized from the point of view of philosophy itself, and not from external to it norms of bourgeois right.

Fortunately, we have a recipe for the completely bloodless destruction of ideologies, through the destruction of the conditions of their existence, discovered by K. Marx and F. Engels during the study of the materialist understanding of history. But this mediated relation of materialism to ideologies is too militant and suggests expropriation of ruling class in general and expropriation of property of all ideological state apparatuses. Therefore churches and other ISA’s as fradestering organizations will not functioning with taxation of 100% of their income and stable growth of level of life in whole society. People with satisfied needs will not go to church, to astrologers, to bourgeois humanists — and clericals, astrologers and humanists, deprived of property, will not be able to spread their ideas to the masses. Thus, within one or two generations, false ideas will cease to be reproduced and will disappear without the slightest bloodshed, which was largely achieved in the USSR and in contemporary China.

So we have two ways of destroy of false consciousness as an environment of application of inconsistent concepts: immediate and mediated, extermination and strangulation, Enlightmental and Marxist, violential and compassive.

But both this ways suggests existence of human beings as carriers of false or true ideas, and components of society. And this is a problem because humanity is a form of personification of assemblages together gods and ghosts.

Assemblages theory is sublates this problem and reframe basic question in terms of memetic ecology.

In projection of unfolding and destruction of conceptual systems we should be guided not love to humans or hatred to lies, but only reason itself.

Because only rational action according properties of memetic system may be develop it and do not harm it. A careful, prudent, economical attitude towards all forms of social matter important for the further development of society should become the principle of practical materialism in changing the world for the better.

We must scrutinize anthropomorphizing interaction interfaces and the spaces of production beyond their surface. And the first subject of study we must take is the history of philosophy itself as the history of impersonal assemblages, ordered according to the principle of contiguity. The subject of philosophy — according Deleuzian metaphilosophy — is a set of observational and communicative positions, ordered syntagmatically, according to contiguity and rupture, in contrast to scientific assemblies, in which the ordering occurs paradigmatically, according to the principle of logically generalizing similarity.