Assemblage concept

- 1. Definition of assemblage

- 2. Meaning of the concept of assemblage

- 2.1 Genesis of the concept of assemblage

- 2.2 Place in the hierarchy of concepts

- 2.3 Place in the network of concepts

- 2.4 Interpretations of the concept of assemblage and their criticique

- 3. Usage of the concept of assemblage

- 3.1 Usage of the concept of assemblage in philosophy

- 3.2 Usage of the concept of assemblage in the sciences

- 3.3 Usage of the concept of assemblage in politics

- 3.4 Usage of the concept of assemblage in art

It is always important in the beginning of consideration of any particular term to keep in mind the structure and order of definition. Every concept presupposes a certain meaning in itself, as well as a double system of references — to other signs and to problems, to the solution of which it required. Accordingly, we can assume the following structure of the dictionary description of terms:

1. Definition — what kind of object, property or relation is meant by this word. Any definition is given by subsuming it under a more general concept, as well as indicating the constituent elements of the defined concept and the relationships between them. In this case, the definition should be derived from the logic of reality itself, and not taken out of thin air or from common interpretations in a ready-made form.

2. Meaning — how this term came about, what others it is connected with, what interpretations and errors in use it has;

- social and conceptual genesis — what was the series of terms that preceded this one, and what social reasons gave rise to them;

- place in the conceptual hierarchy — which concepts this term is subordinated to, and which it defines;

- place in the conceptual network — which groups of terms this term is associated with;

- interpretations and their criticique — how significant philosophers interpret or have interpreted this term, why and how some of these interpretations are erroneous.

3. Usage — what philosophical questions does this term answer, and how is it used in various fields:

- in philosophy

- in sciences (mathematics, natural, social)

- in politics

- in art.

Thus, by describing the concept of assemblage, we simultaneously describe the assemblage of the concept — its definition as a realistic part, meaning as a structure of meaning or philosophical possibilization, and use as a structure of social and activity possibilization.

1. Definition of assemblage

Assemblage is a process of generation, distribution (logical, factual and hybrid connection, interaction and separation) and destruction of objects and spaces existing separately and in systems of relations.

The concept of assemblage is derived from the intuition about the materiality of motion. Indeed, the presence of motion in the world is an obvious fact. It is also obvious that neither motion is possible without that which moves, nor the existence of anything outside motion. But in order for motion to take place, its substrate must be split into objects that move and spaces where they move.

However, since both objects and spaces can move not only relative to each other, but also relative to the systems of their interaction — objects in systems of objects and positions in systems of places — then the substrate of motion must be split a second time in relation to objects and positions in themselves and taken in systems of relations.

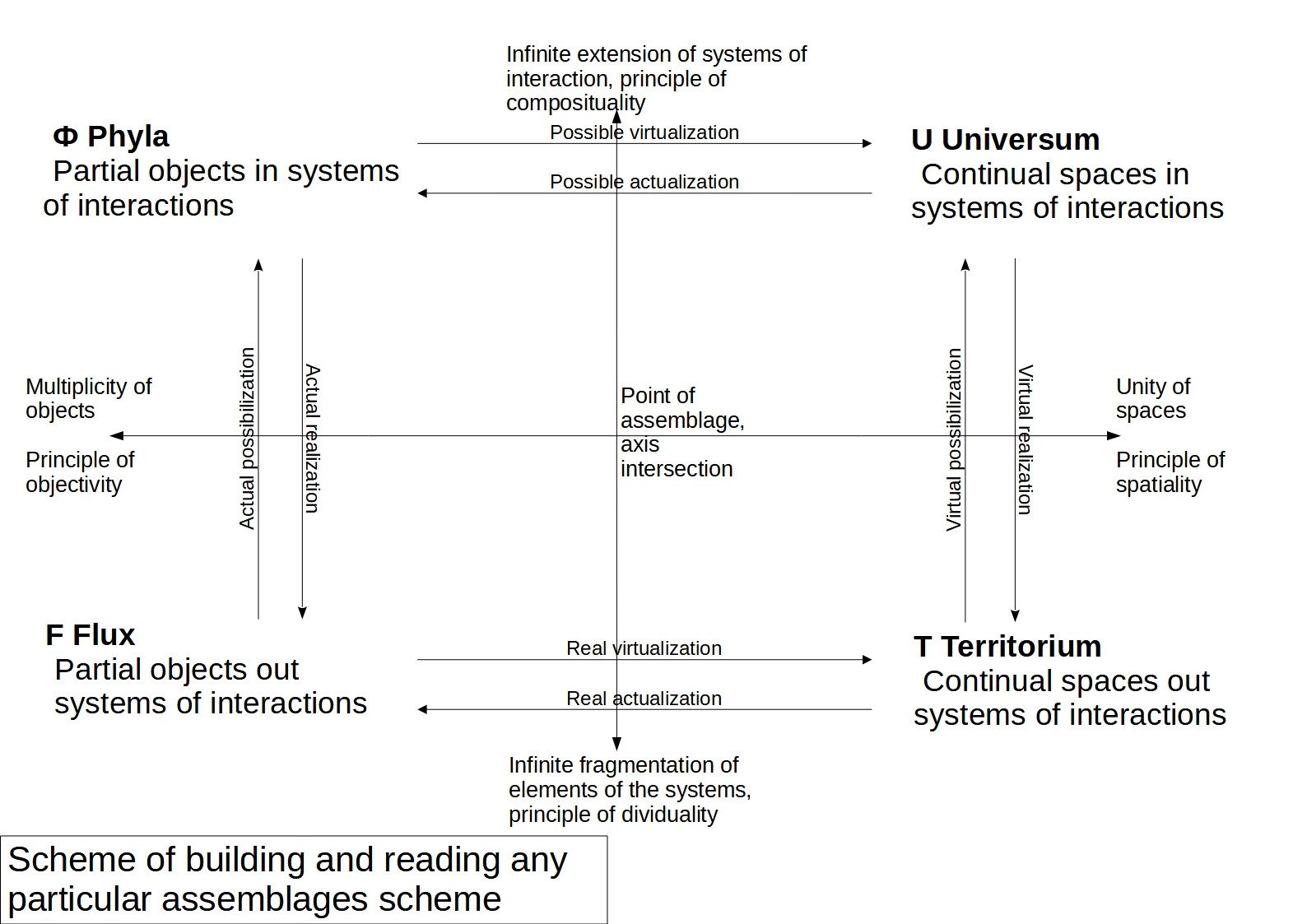

Thus, from the intuition of the materiality of motion follows the universal division of every fragment of reality along two axes:

The horizontal axis is many discrete actual — a unified continuous virtual goes back to the ancient distinction between atoms and void, completed thanks to the Deleuze-Guattarian difference between actually existing desiring machines, composed of sets of flows and their cuts that are irreducible to each other — and a virtually existing body without organs as an immanent limit aleatory combinatorics of a system in the space of which machines and flows are distributed. Elementary transitions along the axes can be characterized as actualization (multiplication, discretization) of virtual unities and virtualization (continualization, unification) of actual sets, respectively. Derived transitions can be designated as deactualization, reactualization, demultiplication, remultiplication, dediscretization, rediscretization — as well as devirtualization, revirtualization, decontinualization, recontinualization, deunification, reunification, etc.

The vertical axis of finite real — infinite possible is built as a difference between elements (flows and territories as the sublated atoms and voids of Democritus) and systems of interaction (phylums and universes as the sublated basis and superstructure of Marx). At the same time, elementary transitions of ascension are interpreted as deterritorialization, possibilization and consolidation of finite flows and territories in the direction of infinite diversity and intensive durations; while the elementary transitions of descent are interpreted as the reterritorialization, realization and liquidation of infinite manifolds back to their initial components. Derivative transitions are designated according to the same system through the prefixes de- and re-, if we are talking about the opposite or return motion, respectively (if necessary, modified according to the rules of the Latin language): impossibilization, repossibilization, deconsolidation, reconsolidation, derealization, rerealization, deliquidation, reliquidation.

Accordingly, at the intersection of these axes there are four types of elements of reality, the existence of which follows from the development of the concept of motion:

The structure of fields, or in Guattari’s own terminology, domains, represents specific ontological groups of assemblage elements. Moreover, what is essential in constructing the scheme is precisely the difference between the actual and the virtual, that is, the multiplicity of desiring machines and the unity of the body without organs, splitting into flows and phyla, and into territories and worlds, respectively. In this case, we can say that the left and right parts of the diagram are arranged as rows of mediation, in which the machines themselves and the BwO are located in the plane of the horizontal line separating the upper and lower parts of the diagram. Accordingly, the logic of ascension takes the following form for the left and right parts, respectively: flows, desiring machines as cuts of flows, machine phylum as flows of cuts; territories, a body without organs as a mode of distinguishing territories, universes as territories of distinctions.

F (f) — Flows. In the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari, a machine is defined as a cut or cross-section of two or more flows — whereas the flow itself can be more strictly defined as a reproducing sequence of segments (or modes of material substance); segment — as an internal structural element of a flow; cut — as mutual external determination of two or more flows.

Φ (φ) — machine phylum. If a machine is defined as a cut of flows, then a phylum can be defined as a more abstract category — a flow of cuts capable of acting as its segments in the process of posibilization.

T (t) — existential territories. Unlike flows, territory as an entity involved in a body without organs as a virtual unity of the immanent limit of the aleatory combinatorics of the system is not determined through production — but rather through anti-production, a way of braking, accelerating and restarting the actual parts of the system.

U (u) — worlds or universes. If a body without organs is defined as a mode of distinguishing territories, then universes should be defined rather as territories of distinctions, possibilizing positions in systems of increasingly complex logico-spatial distinction.

Such are assemblages in static terms, from the point of view of their division and composition. Assemblages in dynamics suggest, as a first approximation, three groups of transformations, each of which includes at least three concepts.

The first three of them are related to the fact that assemblages are something that specifically exist. In other words, any specific mode of substance is an assemblage, and vice versa, any assemblage is a mode or way of existence of a substance. Thus, the existence of assemblages is universal and at the same time concrete, because they are empirically observable. At the same time, the question of the emergence, distribution and destruction of the assemblages themselves, their component parts and the relations between them, is problematic, since it is clear that nature as a whole does not change, and all possible assemblages always take place in it.

In this sense, from the point of view of substance, all possible emergences, changes and destructions are already always distributed throughout eternity, due to which the substance itself is defined as isonomy — the reality of all possible. Therefore, the description of assemblages as arising, changing and dying is only a relatively true description from the point of view of the produced nature of which we ourselves are a part. As for the categories themselves, they can be given the following definitions:

1.1 Emergence — the beginning of the existence of new assemblages due to the connection of parts and wholes destroyed in a certain way.

1.2 Distribution — the duration of connecting and separating parts and wholes of an assemblage in a certain way.

1.3 Destruction — the end of the existence of assemblages due to the separation of their parts and wholes by other assemblages, ending a certain method of connection.

2.1 Logical — expressed in terms of the attribute of infinite thinking. Relation is the logical mutual negation of two or more entities in the process of assemblage.

2.2 Actual — expressed in terms of the attribute of endless motion. Connection is the actual mutual negation of two or more entities in the process of assemblage.

2.3 Functional — expressed from the point of relation between both attributes. Function — mutual mediation of connections and relations.

3.1 Connection — the emergence of a connection, relation or function.

3.2 Interaction — the distribution of a connection, relation or function.

3.3 Disconnection — destruction of a connection, relation or function.

A certain mode of connecting and disconnecting parts and wholes, allowing one assemblage to be distinguished from others, is a function — a set of feedforward and feedback loops that determine the assemblage into existence. The multiplicity of functions that determine the assemblage is its actual subject — the rhizome, which normally combines genetic, hierarchical and network groups of connections, functions, and relations.

In other words, rhizomes are algorithms of assemblages.

2. Meaning of the concept of assemblage

Since the concept of assemblage is also assembled, like all other modes of substance, then, like them, it is characterized in three ways: genetic, hierarchical and network ways. Let’s look at them in order.

2.1 Genesis of the concept of assemblage

The condition for the assemblage of the concept of assemblage as a social phenomenon is obviously is the assemblage of society. Which, as a special form of the motion of matter, is based on two previous ones — physico-chemical and biological, at the junction between which instrumental-linguistic activity developed as the essence of the social form of the motion of matter. An extensive anthropological and linguistic analysis of ancient cultures could reveal proto-philosophical concepts of tribalism, of which the concept in question is a distant descendant. From the available material, attention should be paid to the structures of kinship and the logic of bricolage discovered by Lévi-Strauss, the concept of multinaturalism by V. de Castro, as well as studies of animism and beliefs close to it. However, the methodological principle of compactness encourages us to leave the study of pre-social forms of motion of matter and proto-philosophical views of ancient societies for a separate consideration.

With some certainty it is possible to trace the history of the concepts that preceded the concept of assemblage for literate societies, starting from Ancient Greece to the present day.

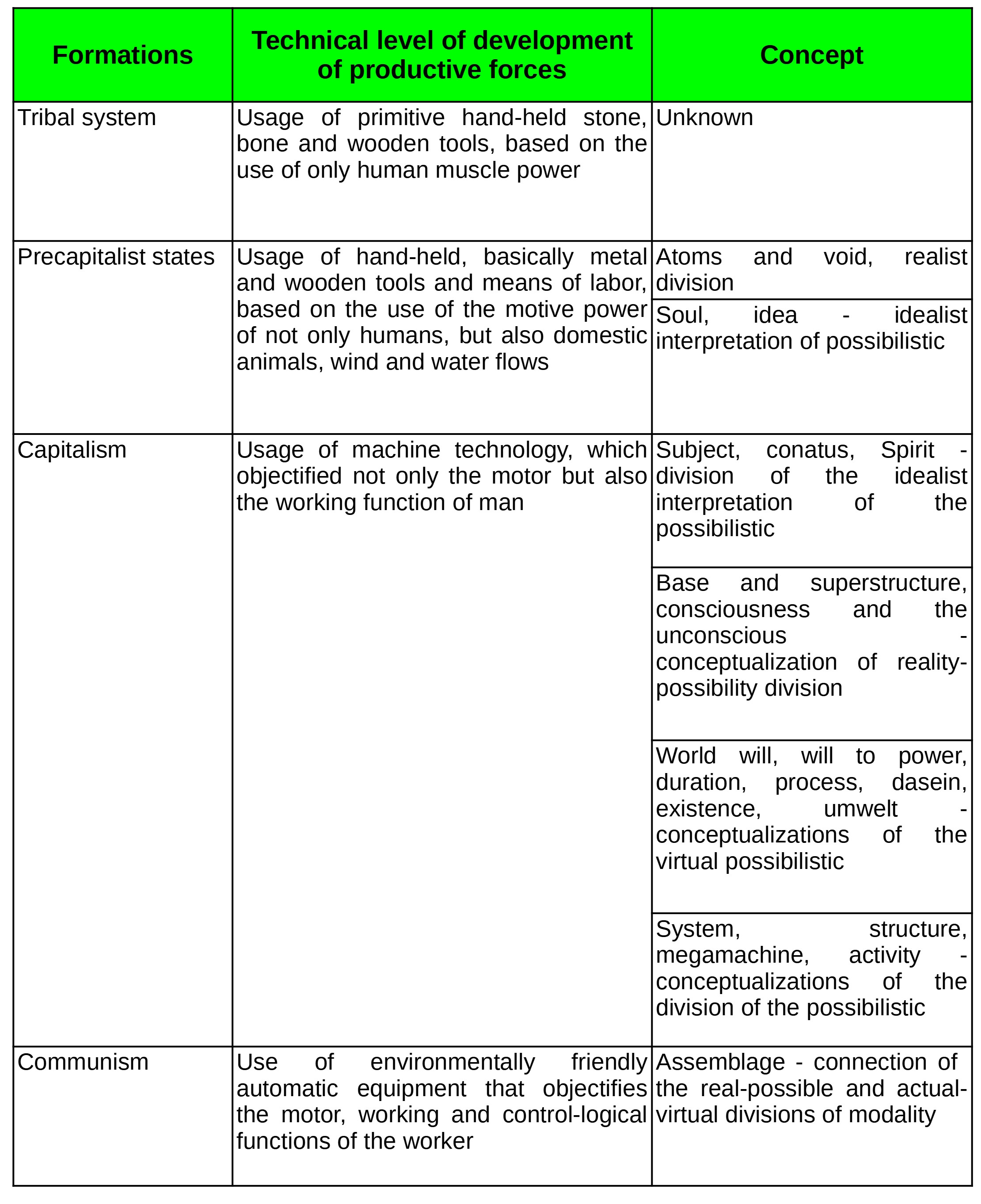

In the history of philosophy, the initial distinction characteristic of the ontology of assemblages can be dated back to the time of ancient atomism. It is the atoms and emptiness of Democritus, written in the lower half of the diagram, that are the starting point of this ontology. Their social cause is ancient protoscience and natural philosophy associated with the initial forms of subordination of the productive forces.

However, ancient protoscience could not provide comprehensive material for a materialist explanation of mental and social life, while at the same time allowing us to observe its difference from real processes, which was expressed in the concept of the soul as an idealistic attempt to conceptualize the possibilistic dimension of the assemblage.

The next stage in the formation of the concept of assemblage is the categories of new European dialectics, such as the subject of Descartes, Spinoza’s conatus or the Spirit of Hegel, expressing the assimilation of real assemblages on the basis of capitalist technoscience and the corresponding division of labor as differentiation of the possibilistic field. Accordingly, the idea of the soul as an indivisible substance is questioned — already the Cartesian subject contains two selves, the thinking and the conceivable, united by a meaning gap. Hegel’s system reaches in this direction the historical limit of possible differentiation, giving rise, on the one hand, to attempts to break through humanism in the form of Marx’s historical materialism, but also to a whole range of reactions of a continualist nature.

It is also worth highlighting the distinction between base and superstructure in the works of Marx and the distinction between consciousness and the unconscious in the works of Freud as a conceptualization of the division of the possible with macrofixation and microfixation. In fact, Marx’s already completely assemblative conceptualization remains this way only for the macro level of socio-historical relations, while at the meso level he retains a residual humanism, oscillating between defining activity as human — or as instrumental-linguistic. In Freud, on the contrary, the individual unconscious is thoroughly dissected, while in the field of social relations a humanistic obscurantism remains, in the light of which the machinery of desiring production, discovered by him in his early years, is reinterpreted in a familialist key.

In this sense, a number of concepts in the philosophy of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are not immediately prior to the concept of assemblage. These include Schopenhauer’s world will, Nietzsche’s will to power, Uexküll’s umwelt, Bergson’s duration, Whitehead’s process, Heidegger’s dasein or Sartre’s existence. All of them express the continualist dimension of the same new European subjectivity, which distinguished itself from the objective world through the differentiation of instrumental activity in the conceptualization of the virtual possibility.

More immediate predecessors of the concept of assemblage can rather be called the cybernetic-sociological concept of a system, especially in the interpretations of Wiener, Parsons and Luhmann; linguistic, sociological and anthropological concept of structure; concept of megamachine by L. Mumford; as well as the concept of activity in Shchedrovitsky’s system-thought-activity methodology. All of them represent quite clear conceptualizations of the division of the possibilistic, so that, taking into account already existing achievements, it becomes possible to combine the reality-possibility and actuality-virtuality divisions in the concept of assemblage, which was done for the first time in the philosophy of F. Guattari and G. Deleuze.

All this can be expressed in the form of the following table:

In each of these conceptions specifically reflected the plasticity of social matter as a possibilistic dimension of assemblages, expressing the sufficient development of social sciences and technologies to posit sociality itself as a subject of reassembling. At the same time, we are faced with Marx’s idea: philosophy and philosophical concepts do not have their own history — or rather, it is completely determined by the logic of the development of material production and social superstructures. In part, this is reminiscent of Platonism, with the important difference that the essenses, the reflection of which is the reality around us, would not be located in the other world, but, on the contrary, in the productive depths of reality itself, to the surface of which waves of deep motions of social assemblages diverge, too huge to observe them directly, but at the same time perceptible by means of scientific analysis of historical processes.

2.2 Place in the hierarchy of concepts

Today, many philosophers actively oppose any hierarchical systems, and often the very concept of hierarchy as an authoritarian and/or outdated concept, trying to oppose it with network and horizontal structures, flat ontologies and other attributes of democratic materialism, designed to show how modern and democratic its apologists are. Often, attempts are made to interpret the concept of assemblage in this context. For example, in “The New Philosophy of Society”, Manuel Delanda contrasts it with essences and totalities as a non-essentialist concept that excludes the possibility of totalization, the fallacy of which interpretation has already been partially stated in the article “Social Constructivism of Ilyenkov and Delanda” (RU version of the article).

Without going into detailed theoretical criticism of such interpretations, it should be noted that they are obviously methodologically flawed. In fact, of the four rules of the method set out by Descartes in his Discourse on Method, when hierarchization is abandoned, the third and fourth principles are clearly violated — the ascent from simple to complex and from basic to derivative, as well as the completeness of the list, since the principle of its construction is based on In the absence of distinction between simple and complex, main and secondary, it becomes unclear. In addition, the first and second rules of the method are implicitly violated, since the problem of dividing difficulties into parts and the task of achieving reliability become unattainable if the order of reasoning and the completeness of the conditions are discarded as unnecessary.

Therefore, one can, with a clear conscience, leave philosophical egalitarists to enjoy equality with themselves, with flatworms, with burrs on nails — with whatever they want — and get busy observing things that are more essential, namely, infinite substance, its attributes and modes that form the obvious and natural hierarchy of existence. In this case, the entire set of philosophical concepts can be divided into three groups: substantial, attributive and modal

1. Substantial categories in themselves. These include the categories of substance as its own cause; attributes as ways of observing it and modes as observable states of a substance. This also includes the concepts of matter and nature that characterize the reality and possibility dimension of substance. Here dialectics is defined as a way of being of a substance through negation, expressed in the splitting of opposites.

2.1 Attributive categories themselves. These include two well-known attributes — endless motion and endless thinking, as well as the categories of their elementary changes — displacement, distinction, combination, identification, distribution, deduction, compression, induction and their derivatives.

2.2 Their consequences for substance. These include the distinction between the producing nature and the produced nature, as well as the already familiar marking of the axes of the assemblage.

3.1 Modal categories themselves. These include the concepts of essence and existence, as well as assemblage as their concrete unity, the universal determination of mode.

3.2 Their consequences for attributes. These include the concepts of meaning, kinetic and functional isonomy as a consequence of the universalism of assemblages, as well as the classification of contradictions.

3.3 Their consequences for substance. These include the concept of nature as a consequence of material isonomy, as well as specific characteristics of parts, wholes and algorithms for their coexistence.

From here we see that assemblage is a key modal concept that is well integrated into the hierarchy of concepts of materialist dialectics and is, in a sense, its foundation. Further clarification of this position is possible by determining a complete list of adequate categories and their hierarchization.

2.3 Place in the network of concepts

We already know that genetically it is associated with the concepts of atoms and emptiness, soul, subject, conatus, spirit, basis and superstructure, consciousness and unconsciousness, world will, will to power, duration, process, dasein, existence, umwelt, system, structure, megamachine and activity; and hierarchically — with the concepts of substance, attribute, mode, isonomy, matter and nature, as well as indirectly with the concepts subordinate to them. Finally, we turn to the position of the concept of assemblage in the conceptual network of contemporary materialism.

The network interpretation differs from the hierarchical and genetic interpretation in that the network has neither a beginning nor an end, but only a selected starting point and paths — lines connecting the points of the graph. Therefore, the presentation of connections between the concept of assemblage and other groups of concepts in this case will be partly arbitrary.

1. Relative categories. Relative categories or categories of relation are understood as the already mentioned categories of bearing-connection-function, as well as their extensions: direct and inverse connection, positive and negative, loop, node, network, actor, rhizome, essence as a set of relations, etc. The assemblage acts in relation to relative categories and phenomena as their actual material substrate.

2. Causal categories. Causal categories are understood as extensions of the concept of cause: the cause itself as a producing factor of its effects; condition as background causality; accident as the generation of consequences by unrelated causes and conditions; regularity as the generation of consequences by a system of interconnected causes and conditions. It is clear that the main axes of the assemblage directly correspond to these categories: the actual-virtual corresponds to cause-conditions, and the real-possible corresponds to contingency-regularity.

Probability is a measure of the possibility of a given set of causes and conditions generating certain consequences in the process of assembling certain consequences — and vice versa, a measure of the likelihood that these consequences were generated by one and not another set of causes and conditions. The probability varies from necessity (100%) to impossibility (0%) of the occurrence of an event.

Selection is an algorithm of cutting the probability spectrum of possible consequences in the assemblage process.

The classification of causes according to Aristotle correlates with the concepts of assemblage as follows: a productive cause characterizes the generating ability of the original set of causes and conditions; the aim-cause characterizes the formation of the effect as an autopoietic cause of itself; the material cause characterizes the real material that accidentally entered into a given assemblage; the formal reason characterizes the possibilistic system of relations that necessarily formalized this assemblage.

3. Dialectical categories. By dialectical categories we mean the categories of dialectics in the narrow sense — as the universal logic of the motion of matter. These include the following groups of categories: identity, unity, difference, opposition, contradiction, conflict, antagonism; universal, special, singular; negation and negation of negation; quality-quantity-measure, etc. All of them characterize the method of assemblage “from top to bottom”, from the possibilistic to the real on the basis of the possibilistic as necessary.

4. Aleatory categories. Aleatory categories refer to the categories of aleatory materialism or encounter materialism, developed by Louis Althusser based on his own interpretation of ancient atomism, which partly influenced the materialism of Deleuze and Guattari. Aleatory categories include the following concepts: meeting, case, collision, situation, event, structure, determination, overdetermination, filtration, sense-nonsense, difference and repetition, etc. All of them characterize the method of assemblage “bottom up”, from the real to the possible based on reality as accidental.

5. Nomological categories. Nomological categories mean extensions of the concept of regularity as a stable connection of causes and consequences, form and content — regularity, anomie, nomo-object, anomo-object; necessity, expediency, purpose, freedom. These categories characterize the combination of the possibilistic and realistic aspects of the assemblage, their dialectical and aleatory construction.

6. Essential categories. Essential categories mean extensions of the concept of essence as a set of relations that produce certain objects as their consequences and/or components: object-essence-modus-attribute-substance; simulacrum, spectrum, assemblages, contrary to popular interpretations, are the actual essences of objects, since they are generated by the processes of self-organization of matter.

7. System categories. System categories mean extensions of the concept of a system as an ordered set of elements, positions and relations between them: observation, reflection, communication, information, message, understanding, etc. System categories characterize universes as a domain of virtual capabilities of assemblages in terms of information processes.

8. Stratification categories. Stratification categories mean details of the concept of a strata as an assembled one — a product of the functioning of assemblages with a finite set of components and algorithms for their interaction, limited by other strata. Strata can be considered as assemblages closed in their own reproduction. Stratification categories include the following concepts: material, form, content, expression, division, functive, function, paradigm, syntagma, constant, variable, interdependence, determination, constellation, correlation, relation, system, process, division, division, complementarity, solidarity, specification, selection, autonomy, combination, etc. assemblages in the proper sense refer to strata as their products and to the materials from which they draw materials for their construction. Obviously, Hjelmslev’s Glossematics is especially important to understandeing of this ontological group of concepts as an example of amazing stratification of language science.

9. Becoming categories. Becoming categories mean the concept of becoming and its possibilistic extensions. In Deleuze and Guattari’s ontology, becoming is defined as an interassemblage, that is, a process and space of interaction between two or more assemblages. In this prospect there is bbright comparison of two concepts: becoming as interassemblage and plane of consistency as interstrata.

10. Plication categories. The plication categories mean the concept of fold and its possible extensions. The relation between the concepts of assemblage and folding is not fully thought out in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari, and requires additional research. To a first approximation, the concept of folding expresses a virtual interpretation of the posibilization process. It is also possible to connect the concept of a fold with the topological categories of rupture, gluing, surface, striation and smoothing, etc.

11. Genetic categories. Genetic categories mean categories that describe the process of inheritance of elements and assemblage algorithms. These include concepts such as heredity, variability, selection, etc.

12. Nomadological categories. Nomadological categories mean concepts that express the mobility of assemblages in space, in contrast to stratified modes. Nomadological categories include such concepts as: place, body, motion, energy, engine, cohesion, aiming, etc.

2.4 Interpretations of the concept of assemblage and their criticique

Among the available ways of understand the concept of assemblage, the following interpretations can be distinguished:

1. Eclectic understanding. The most common way of understanding the assemblage, as well as most of the other terms of Deleuze and Guattari, is that it can and should be understood as anything — any list of partial objects, in the spirit of Jane Bennett, who begins her treatise "Vibrant Matter" with a list material objects that, in her opinion, are worthy of our attention: a black glove, oak pollen, a dead rat, a bottle cap and a wooden stick. In the same spirit, the concept of assemblage is understood in vulgar Deleuzianism as a random enumeration of any objects, while being spaceless and representational. It is clear that such an interpretation is not able to explain motion, development and their specific forms that interest us.

2. A more advanced interpretation of the concept of assemblage is offered by the Mexican-American philosopher Manuel DeLanda. It relies on the Deleuzo-Guattarian division of assemblage along four axes: actual-virtual and territory-deterritorialization. However, in his understanding, the actual-virtual axis is interpreted as material-expressive, thereby his entire scheme turns out to be a spaceless crowd of objects, crowded on top of each other and not having free space to move. Thus, the motion is unthinkable in its interpretation, which is why it should be rejected by us as clearly erroneous.

3. Ian Buchanan, Australian philosopher, criticizes the concept of assemblages as presented by Delanda, insisting that the original meaning of the actual and virtual in the texts of Deleuze and Guattari is exactly the opposite: in his opinion, the actual are the continuous and intelligible productive mechanisms, and their fragmentary representations are virtual, that is gived empirically. However, in essence, this scheme is no better than Delanda’s, since it is still spaceless, and without understanding the virtual as space, motion turns out to be unconceivable, and after it, all its specific forms, which are the subject of research in specific sciences.

4. Finally, the concept of assemblage outlined in this text, which takes into account the errors of previous interpretations, primarily non-reflexivity and spacelessness, and also establishes the exact meaning and scope of categorical relations, opens up the wide application of this concept in philosophy and other fields of activity.

3. Usage of the concept of assemblage

3.1 Usage of the concept of assemblage in philosophy

As for the use of the concept of assemblage in philosophy, we have already clarified its genesis and role in the construction of an integral conceptual system of philosophical materialism, and its development. Let us point out some other ways of its application in philosophical disciplines:

1. Proof of the substantiality of matter and establishing the boundaries of the cognition of matter — in other words, the solution to the general question of philosophy in its ontological and gnoseological aspects.

2. Solving the problem of the universal element of reality, because the universalism of assemblages is associated with the inclusion and mutual limitation in this concept of four possible deviations: particularism, holism, reductionism and emergentism, each of which in itself serves as the basis for the corresponding metaphysics, while in mutual limitation they allow the formulation of a dialectical and at the same time materialist worldview.

3. Criticique of humanist ideologies, conceptually based on corresponding metaphysical deviations from the dialectical unity of aspects of the assemblage, and associated with the assertion that society consists of humans as finite and universal elements, while the humanist markup is the effect of impossibilization of assemblages in the human condition.

4. Solution to the problem of the subject of the transhumanist transition — which directly follows from the previous position: if it is not humans who are real, but assemblages that are in the human condition, then the essence of the matter is to free ourselves from it through further technical and social posibilizations. If humans are the final members of society, as humanism claims, then it is not clear who or what should overcome humanity in the process of singularity — which in turn leads to empty talk about the extermination of humanity by artificial intelligence and other reactionary fables.

5. Also, the concept of assemblage plays an important role in materialist ethics, since the subject of ethical attitude is not individual subjects outside the conditions of their existence, but material processes and spaces for their implementation, jointly included in the process of posibilization — the collective growth of the capacity to exist.

6. In addition, the concept of assemblage answers the question about the essence of the beautiful, ugly, comic, tragic, sublime and other aesthetic categories, which can be clearly and distinctly understood in terms of the balance and imbalance of the opposites assembled in the process.

7. Finally, the concept of assemblage is applicable in metaphilosophy, as was demonstrated when considering the philosophical methods of Descartes, Deleuze and Althusser in the order of possibilization, from the real to the possible.

3.2 Usage of the concept of assemblage in the sciences

As for the use of the concept of assemblage in the sciences, this area seems too vast for this study, so we will limit ourselves to pointing out those areas of the exact, natural and social sciences where a productive dialogue between philosophers and scientists is possible, the exchange of problems and the search for joint ways to solve them.

1. In mathematics — the question of the nature and origin of quantitative relations in reality and in mathematical theories.

2. In physics, the question of the natural origin of the universe, fundamental interactions and the difference between stuff and field as actual and virtual aspects of physical assemblages.

3. In chemistry — the question of the structure of matter, the operation of the periodic law, the nature of the chemical process and its supramolecular extensions.

4. In biology — the question of a non-reductionist understanding of the subject of natural selection in connection with criticique of the reductionist theory of the selfish gene by R. Dawkins.

5. In economics and sociology — the question of what society consists of and how it relates to biological and physico-chemical forms of the motion of matter; the question of the nature and historicity of social laws; the question of changing historical formations, the end of capitalism and the onset of communism.

6. In psychology — the question of the subject and the boundaries of the psyche, the relation between the biological and the social, the principles and patterns of development.

7. In linguistics — the question of the origin and social nature of language assemblages.

3.3 Usage of the concept of assemblage in politics

In political struggle, the concept of assemblage is applicable in several significant areas, namely:

1. Criticique of reactionary ideologies that affirm eternity or, on the contrary, the arbitrariness of social norms and inhibit scientific, technical and social progress.

2. Better understanding and correction of the propaganda of the theory of scientific socialism by party agitators.

3. Adequate construction of the organization in accordance with the norms laid down at the founding of the RSDLP, in particular the division of leadership into the Central Committee as an organizational body — and the Central Organization as a theoretical body, expressing the actual and virtual dimensions of the party assemblage, respectively. (See also: Lenin abstract machine, and the Bolshevik collective assemblage).

4. Reasoned criticique and avoidance of opportunisms as deviations that impossibilize the political assemblage in one aspect or another.

3.4 Usage of the concept of assemblage in art

In art, the materialist concept of assemblage points to the equivalence of the figurative and background aspects of a work of art, which will allow the spatial aspect to be adequately depicted in works of art, contrary to the tendency to depict incoherent and motionless piles of objects and images in all genres of contemporary art.

In summary, in concept of assemblage we are reached a point of absolute knowing or absolute truth that can not be refused by any subsequent researchs or discoveries.