Forgotten Voices

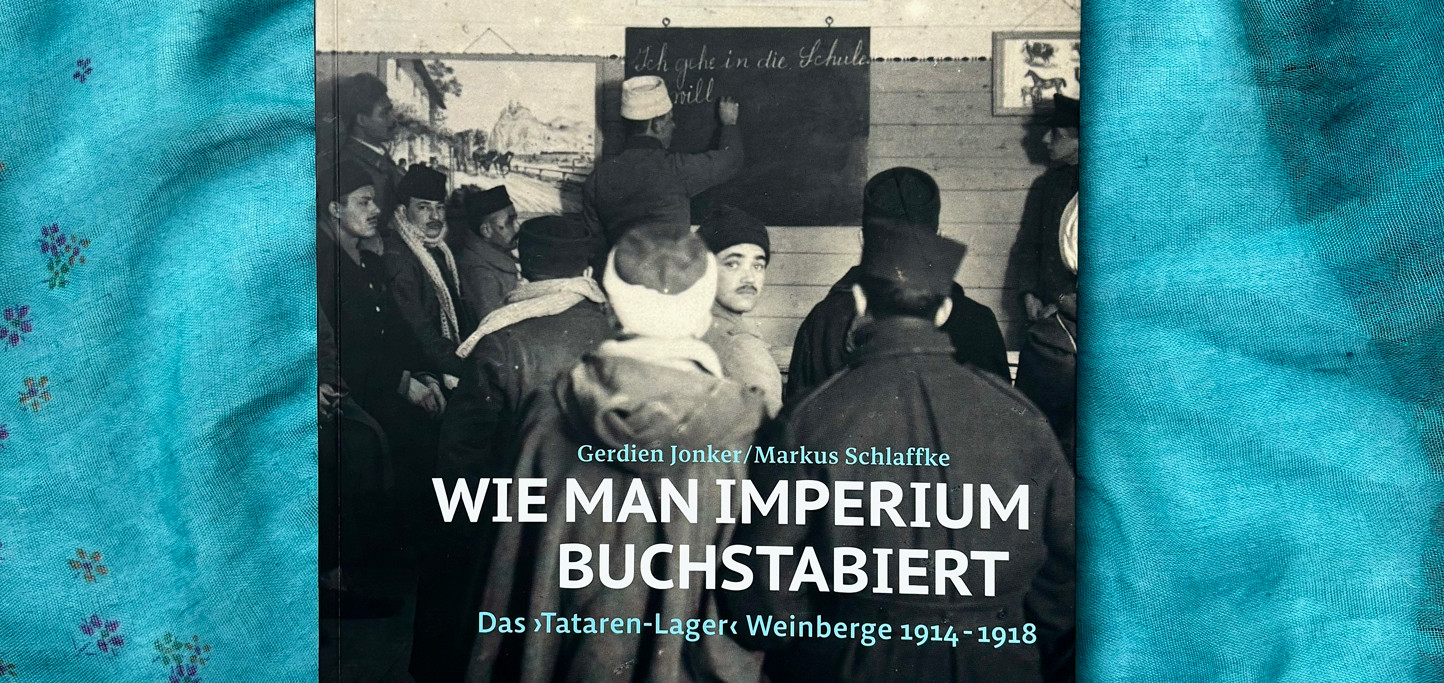

Tatar prisoners of war voices in the imperial strategies

and colonial tactics of German and Russian Empires

- History Unfolding Now*

- Prelude. The coincidence of intention

- Act 1. The curiosity of seekers

- Act 2. Halbmondlager for night "volunteers"

- Act 3. The biomachines failed

- Act 4. Meat for German soldiers

- [no title but memories]

History Unfolding Now*

Denis Esakov

Prelude. The coincidence of intention

The decision to organize a space with allapopp as Voices Otherwise residency at the Open Air Museum of Decoloniality for listening to the voices of Tatar prisoners of German POW camps was something very obvious.

allapopp is a Berlin-based interdisciplinary digital media- and performance artist, originally from Tatarstan in russia. allapopp’s work fuses mixed Tatar, post soviet, queer & migrant exploration with tech-inclusive envisioning, and formally operates within the domains of digital art, performance and sound, interactive live formats and experiences in XR and web.

Curiosity and focused attention to these records from the archive had been in talks for the last couple of years and somehow just jumped into action when we decided to do a collaboration at Alexanderplatz. The archive of shellac recordings is housed in the Lautarchiv [Sound Archive] at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin and can be accessed and researched. It is one of the largest sound archives in the world. German ethnographers and sound recording enthusiasts made many such recordings in the 20th century. The archive describes itself in such words:

The Lautarchiv of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin is an acoustic collection of around 10,000 shellac records, wax cylinders and tapes. It holds mainly voice recordings of: 1. POW-soldiers, recorded during the First World War in prison camps on German soil, 2. public figures in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic and 3. a large number of languages and (mostly German) dialects. The Lautarchiv is one of the earliest of its kind in Europe and is characterised by a focus on phonetic and linguistic interests.

—lautarchiv.hu-berlin.de

A Carpet Pavilion with Tatars’Voices was constructed in the Open Air Museum of Decoloniality square using two carpets—one from allapopp and the other gifted to us by our neighbor Dorothea. Inside the pavilion, the voices of Tatar prisoners can be heard. Outside, there is brief information about this unfolding story. Some people lined up to listen to the voices, some were afraid to go inside, and some entertained their little brothers by smoking a joint made inside of carpets. Leila Almazova played the kurai. allapopp fed everyone Qabartma (traditional Tatar pastry), made a couple of hours earlier. The guy warmly thanked us for the public story about the forgotten voices.

Act 1. The curiosity of seekers

At the same month, we (de_colonialanguage) traveled to Wünsdorf (small town nerby Berlin) to an abandoned Soviet military base to collect artifacts from this space and see what the language of these objects says to visitors to the TAKE aSEAT. MAKE aSHIFT exhibition. Can it function as an alphabet and be assembled into messages? What kind of messages? The first to respond to the information about the field research at this Soviet military base was shared by Anton Ikhsanov, who told the story of this place in a deeper way. This is the story of camps for Muslim prisoners of war (POW), including Tatars, after World War I, in this very place.

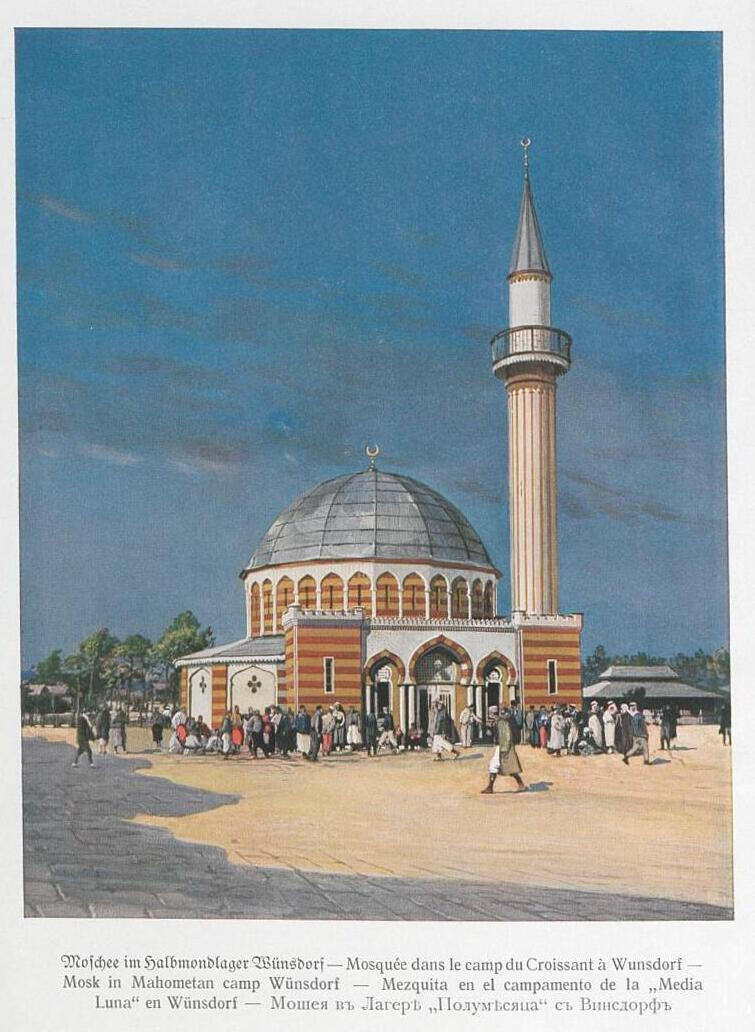

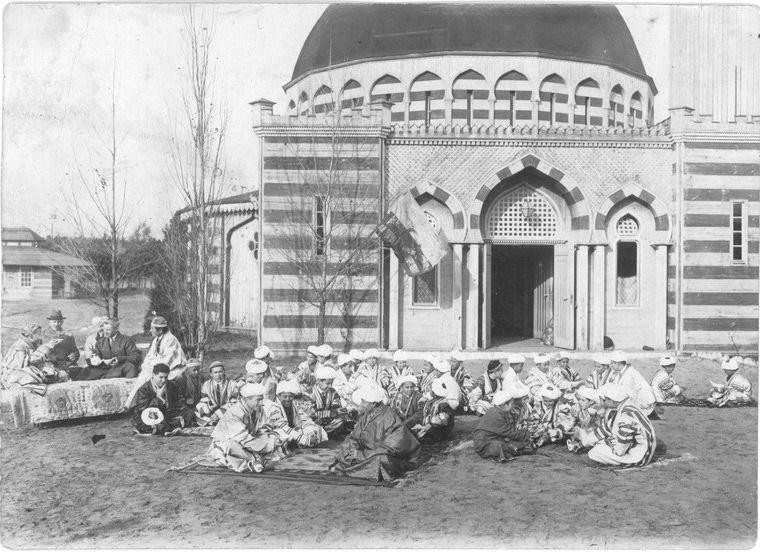

During World War I, German political technology gave rise to the idea that the inhabitants of the colonies of France, Britain, and Russia could be used to stir up religious riots in their homes. Therefore, the Germans built camps for prisoners of war with mosque, where they began to contain people from the colonies. One of them was Halbmondlager in Wünsdorf. There were many Tatars in the neighboring camp — Kriegsgefangenenlager Weinberg. Later, the Soviet military base was built on the site of this camp.

Act 2. Halbmondlager for night "volunteers"

Halbmondlager was a prisoner-of-war camp in Wünsdorf during World War I. The name translates as “Crescent Camp or Half-Moon,” referring to symbols of Islam. The camp held about 30,000 Arab, Indian, and African prisoners of war from the British and French allied armies. The main purpose of the camp was to persuade the prisoners to wage jihad against Great Britain and France in accordance with the 1914 Ottoman jihad proclamation, serving as a demonstration of German military propaganda. The first mosque in Germany was built in this POW camp, a wooden structure that was completed in July 1915. The mosque, built at the request of the Grand Mufti of Constantinople (Ottoman Empire), was financed by the Prussian army and modeled after the Dome of the Rock (Arabic: قبة الصخرة [Qubbat aṣ-Ṣaḵra]), Al-Quds. In 1925–1926, it was demolished due to dilapidation. A subcamp known as Inderlager (Indian Camp) was created to house prisoners from India who were not openly pro-British; those who were pro-British were sent to other camps.

Tunisian researcher Mohamed-Ali Ltaief who was visiting exhibition recounted this story, adding details from his research. For example, he has documents about a poetry reading for rewcording purpose by a Tunisian poet Sadok Ben Rachid, which, according to the documents, took place at 2 a.m. deep at the night. Could such a nighttime recording have been voluntary in a POW camp, or was this practice part of the trials to which prisoners were subjected?

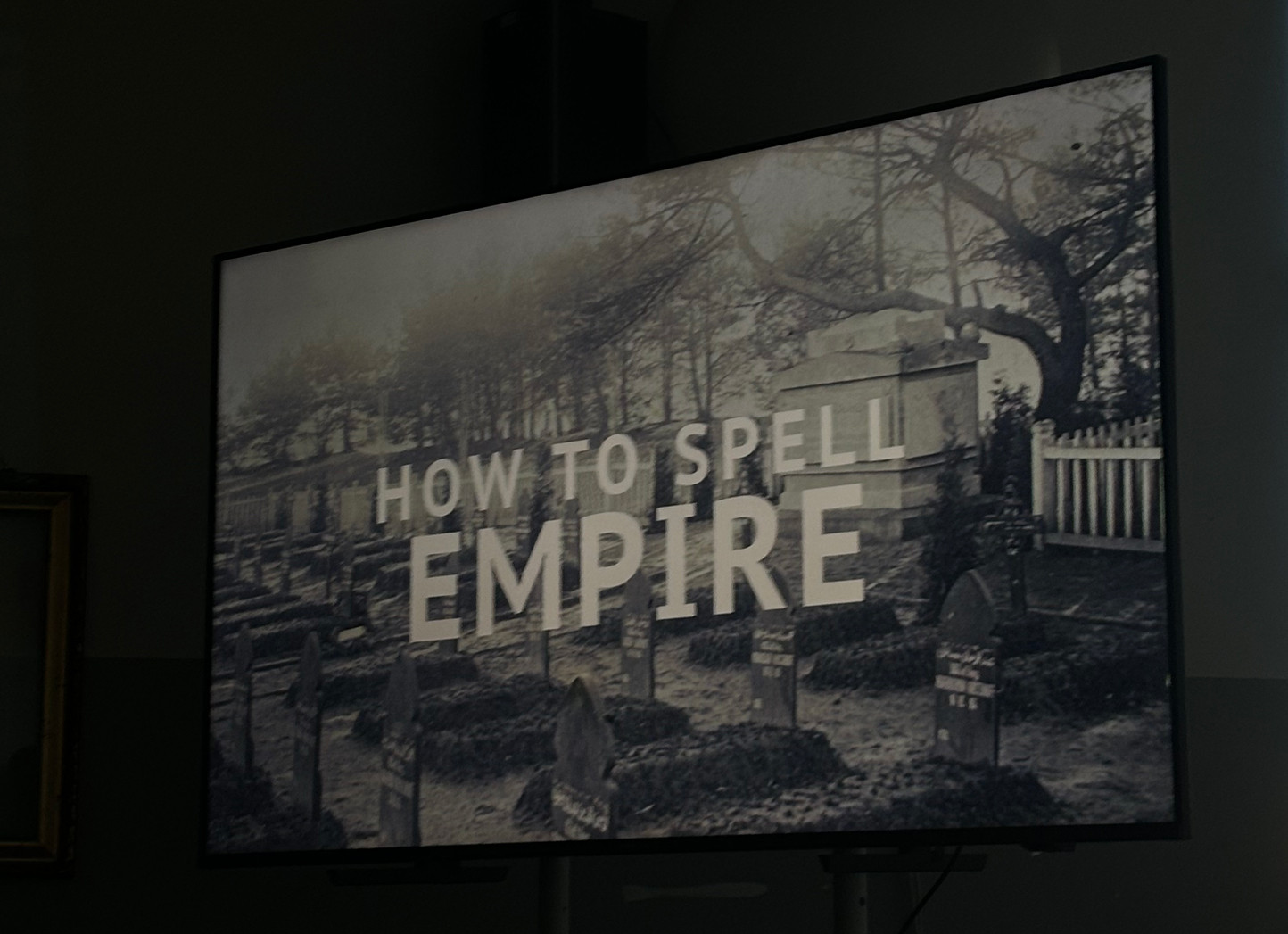

Act 3. The biomachines failed

Next, researchers Leila Almazоva and Markus Schlaffke, who worked on the documentary film HOW TO SPELL EMPIRE, were involved. The film tells the story of the German biopolitical imperial machine, which came up with the idea of indoctrinating prisoners of war with ideologies important to the German Empire. The desired result was to send “correctly ideologized” people back to their countries and have them act in the interests of German politics at that time. These were supposed to be biopolitical machines carrying out German political tasks in other lands.

Yes, the voices of the Tatar prisoners from the Lautarchiv are the very voices of people who underwent the indoctrination program against their will in this prisoners camp. As far as I know, this plan did not work. People did not become biomachines carrying out the tasks of sophisticated biopoliticians. Many of them died and were buried near this camp. Prisoners from other countries, such as India, were also buried there.

The British kept a military archive. They managed to record their part of the cemetery before it was transferred to the USSR. The Soviet military set up a training ground on this site. The military archive with the names of prisoners in Berlin was burned. The Tatar part of the cemetery remained unrecorded. The British part of the cemetery has been restored, and it is possible to find out the names of the prisoners. The Tatar section of the cemetery is abandoned, with no traces of graves and grass growing everywhere. There are no political forces that could take care of this part of history. But there are activists and researchers who are currently restoring the cemetery and writing down the names of Tatar prisoners.

Act 4. Meat for German soldiers

Objects brought from Wünsdorf—artifacts of Soviet and GDR origin—were brought to the Kulturfabrik Moabit gallery (Berlin) to participate in the exhibition TAKE aSEAT. MAKE aSHIFT. Visitors were invited to get the objects out of the shadows of the “museum” and bring them into the light of a public spectacle, thus sparking a conversation about languages and memory. A series of coincidences and unfolding stories led to a screening of Markus Schlaffke’s film and a discussion of this research with Leila Almazova. To a meeting with a researcher of this cemetery and history from Tunisia. And a session of listening to Tatar voices through the work of allapoopp, which was attended by one of Kulturfabrik Moabit residents, who shared the history of this place. Located near the Berlin Wall next to the Main Train Station, it was squatted in 1991 and has been a space for culture ever since. But before that, it was a complex of buildings used as a slaughterhouse and meat storage facility for German soldiers during World War I. The slaughterhouse itself was bombed during World War II and did not remain intact. The meat storage building has been the main building of this cultural space for the last 34 years.

In an impressive way, the whole thing has come a full circle. The voices of Tatar prisoners of World War I, who didn’t carry out the biopolitical plans of the German military machine, sounded a few weeks at September and October 2025, during Germany’s involvement in at least two wars (Palestine and Ukraine), in the space that stored food for German soldiers of the same time of WWI, connecting fragmented stories into a rhizome of unfolding history.

the history is unfolding now

[no title but memories]

Anton Ikhsanov,

PhD fellow at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

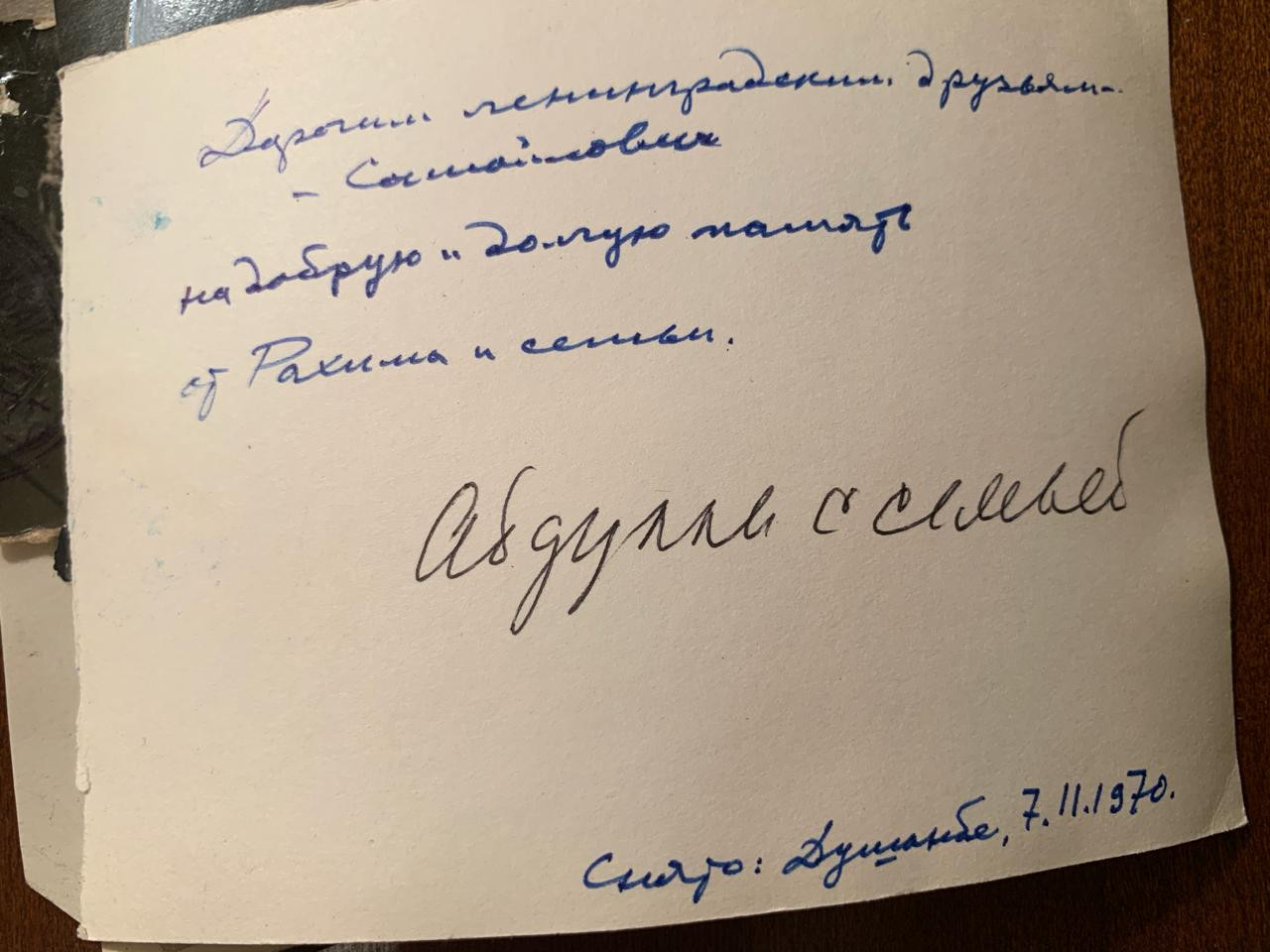

It always begins with an accident. In 2020, during the pandemic, I was sitting in the apartment of Marina P. Samoilovich, the granddaughter of the renowned Orientalist Alexander N. Samoilovich. Marina Platonovna was always very kind and supportive of my research. Because of the lockdown, she created a safe, isolated space for me to work — a room where Samoilovich’s piano stood. I sat by an old-fashioned desk covered with photographs, documents, and medals — everything she had managed to find in her cabinet. I spent hours reading, examining, thinking, and googling various details. At some point, two photographs caught my attention.

The first showed a man wearing a do’ppi, a traditional Central Asian skullcap, with his family beside him. The second depicted the same man sitting alone, with an inscription that read: «To my dear friend and brother Platon Alexandrovich, in memory of how we found each other again after forty-two years apart since our youth together. From Burkhanov Rahim Munzimovich. City of Dushanbe, April 27, 1968. The photo was taken on April 21, 1968».

Curious, I called Marina Platonovna and asked who the man was. «Would you like a cup of tea?» she replied kindly, as she always did. We went to the back rooms of her apartment to sit by the TV, which was tuned to the Culture channel. «Do you see this teapot?» she asked, pointing to an old porcelain teapot made in Bukhara. «You know, in Bukhara, they never throw broken things away. They always try to repair them using a very distinctive method — a metal brace». She showed me a part of the teapot mended with such a brace. «And look at this thread», she continued, pointing to the string that connected the lid to the handle. «He made it — Burkhanov».

Rahim Burkhanov was the son of Abdulvahid Munzim, the first so-called Jadid teacher of Bukhara. In the mid-1920s, the Bukhara Republic signed an agreement with the German government to send its students to Germany for education. Burkhanov was among those selected. Later, when the Soviet government recalled these students to the USSR, Munzim asked the Samoilovich family to host his son. Much later, while browsing Facebook, I came across a photograph titled «Bukhara youth near a mosque in Berlin, 1920s». The mosque became another point of reference in my research. I soon found numerous photographs, documentaries, and texts about a place called Wünsdorf.

This mosque had originally been part of a prisoner-of-war camp. During the First World War (1914—1918), thousands of Tatar soldiers were captured and sent there. The German government, which styled itself as a protector of Muslim communities, built the mosque in an effort to gain the prisoners’ sympathy. I had known this story from history courses — as a kind of meta-narrative about the clash of empires and ideologies — but I had never known the concrete names and personal stories connected with this place.

In 2022, the Full-Scale Invasion began. I moved to Tashkent, seeking asylum in the very region I had spent my entire life studying. There, I visited the Museum of Political Repressions. One of its exhibitions was dedicated to a group of Bukhara students who had been sent to Germany. After their return to the USSR, almost all of them were arrested and persecuted. Their fate has since become a subject of great interest for many historians and journalists in Uzbekistan.

Three years have passed. During this time, I have often returned to an idea from Henning Trüper’s book Orientalism, Philology, and the Illegibility of the Modern World: Is violence the true starting point of history — the ultimate moment from which new meanings emerge? Or is it rather the appropriation of violence by philological practices that turns it into text, retroactively presenting it as the beginning of history?

At that moment, I was arriving in Berlin, invited by Leila Almazova to watch a documentary by Markus Schlaffke about the Wünsdorf camp and its inhabitants. Schlaffke did not focus on the mosque or other material details. Instead, he turned his attention to the voices. The Tatar prisoners of the camp were forced to tell their stories — filtered through ethnographic and anthropological frameworks. German scholars recorded their words, songs, and reflections in an effort to systematise knowledge about the prisoners and their communities. In the documentary, these voices were presented, exposing the violence of the camp’s order, the despair of lost return, and the ache of homesickness. All these motifs intertwined with depictions of mutual bewilderment — experienced on both sides of this encounter, by the Tatar prisoners and the German officers who sought to study them.

At the same time, one of my students in Moscow, Salavat, presented a study devoted to those very songs, which had been printed in Kazan. Salavat was interested in how the traditional genres of bayt and munajat, used by the camp’s prisoners, revealed their emotions and subjectivities — their perceptions of life within the confines of the camp. His topic was closely connected to the recently published work by Allen Frank, Kazakh Muslims in the Red Army, 1939–1945, which examines the songs composed by Kazakh soldiers on the frontlines of the Second World War and in German prisoner-of-war camps.

Once again, violence and poetics, silence and voice intersected before my eyes. My encounter with the Wünsdorf camp had begun with material objects — a teapot and a photograph — but gradually led me toward audio recordings and written texts. Before me lay another group of writings by Samoilovich, produced during the Civil War. Of course, they had little in common with the genres studied by Salavat or Allen Frank. Yet they, too, were born out of political upheaval — moments when history manifested itself through violence and the illegibility of the future. Engaging with these texts and photographs, and experiencing a similar sense of exile, has become central to my reflection on history and the ways it is transformed into text.