Someone 2017: “Anything but Revolution!”

100 years of 1917: no memories?

Silence, emptiness, absence: these are the words that commentators have used to describe the Russian authorities’ response to the 100th anniversary of 1917. It is an exaggeration: the website of the Russian Historical Society, the association that Russian president Vladimir Putin tasked with organising anniversary events, boasts 118 activities (exhibitions, conferences, research projects, public lectures, documentaries, etc.) planned to mark the occasion. Yet the immense and undeniable influence that the revolutionary events of 1917 had on Russia’s past and continue to have on its present (not to mention their impact globally) make the number and scale of the anniversary events strikingly disproportionate.

Commentators have also pointed to Russian citizens’ lack of interest in the events of one hundred years ago. This observation might be simultaneously a reason for and a consequence of the fact that intellectuals remain the principal consumers, as well as the producers, of most projects commemorating 1917. This is characteristic of projects initiated, at the behest of the president, by the Russian Historical Society and more or less independent ones — for instance, the website 1917: Free History. Consequently, while relatively few Russian citizens are interested in reflecting on the role of 1917 in their country’s history, their chances for an accidental encounter with the topic are also quite limited.

Given that the key channels of mass communication in Russia (like federal television channels and national newspapers) have largely disregarded the anniversary, cultural exhibitions take on special significance. The exhibition is inherently a format that allows a relatively large audience to engage with material, but in this particular anniversary context it assumes even more importance — becoming perhaps the most accessible form of public history. By providing opportunities for “accidental encounters” with the past, exhibitions are able to push the limits of reflection on 1917 and create space for new interpretations of the revolutionary events.

The revolution in exhibitions

Whereas exhibitions dedicated to 1917 are not as common in Russia as they could and probably should be, there are still quite a few examples that in one way or another address the anniversary. Here, I take a look at three large thematic exhibitions and attempt to identify similarities and differences in their approaches to thinking about 1917. All three are mounted at state museums in Moscow: “Someone 1917” at the State Tretyakov Gallery, “1917. The Code of Revolution” at the State Central Museum of Contemporary History of Russia, and “Cai Guo-Qiang. October” at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, with the former two included in the Russian Historical Society’s anniversary programme. Two of them — “Cai Guo-Qiang. October” and “Someone 1917” — reflect on the revolutionary events through the prism of art, while the third one pursues a historical approach.

None of the three exhibitions attempt to offer a comprehensive account of all spheres of life in Russia during the revolutionary years, including the events of 1905-1907, the February and the October revolutions of 1917, and the Civil War that followed. This is understandable in case of the two art shows (their strategies are different by default), but from the State Central Museum of Contemporary History of Russia, formerly the Museum of the Revolution, one could expect more.

There are so many questions that this museum’s visitors should be engaged with: Were there several revolutions in the early 20th century in Russia or was it all one revolutionary process, as some scholars believe, and why is this important? What meanings did the February and the October revolutions have then and what do they mean today? Why and how did the new authorities start political repressions? And, crucially, when? (This is not as insignificant a question as it might seem: some still believe that it was Joseph Stalin who first turned to terror, in order to eliminate the enemies of the people in preparation for the war with Hitler). Why were the Russian Empire’s Jews so active in the revolutionary movement and how has this fact been fuelling Russian anti-semitism for decades? What were the multitudinous ways in which the events of 1917 change the country, the continent and, indeed, the whole world? How did they transform our lives, the lives of my friends and my own? What narrative about 1917 could unite, rather than divide Russians? And so on, and so forth.

Some of these questions have been answered by historians, others are discussed by intellectuals and taken up by smaller (and often private) institutions: for instance, “First to Suffer”, an exhibition at the International Memorial in Moscow, tells stories of the Soviet regime’s first victims; another small but important exhibition, at Moscow’s Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, attempts to make sense of the history of “one people in the years of revolution”. Yet, some questions still have no answer. They probably cannot be answered easily, but they certainly need to be asked — first and foremost, at the State Central Museum of Contemporary History of Russia, for, had it not been for 1917, our contemporary history would have been completely different.

“1917. The Code of Revolution”

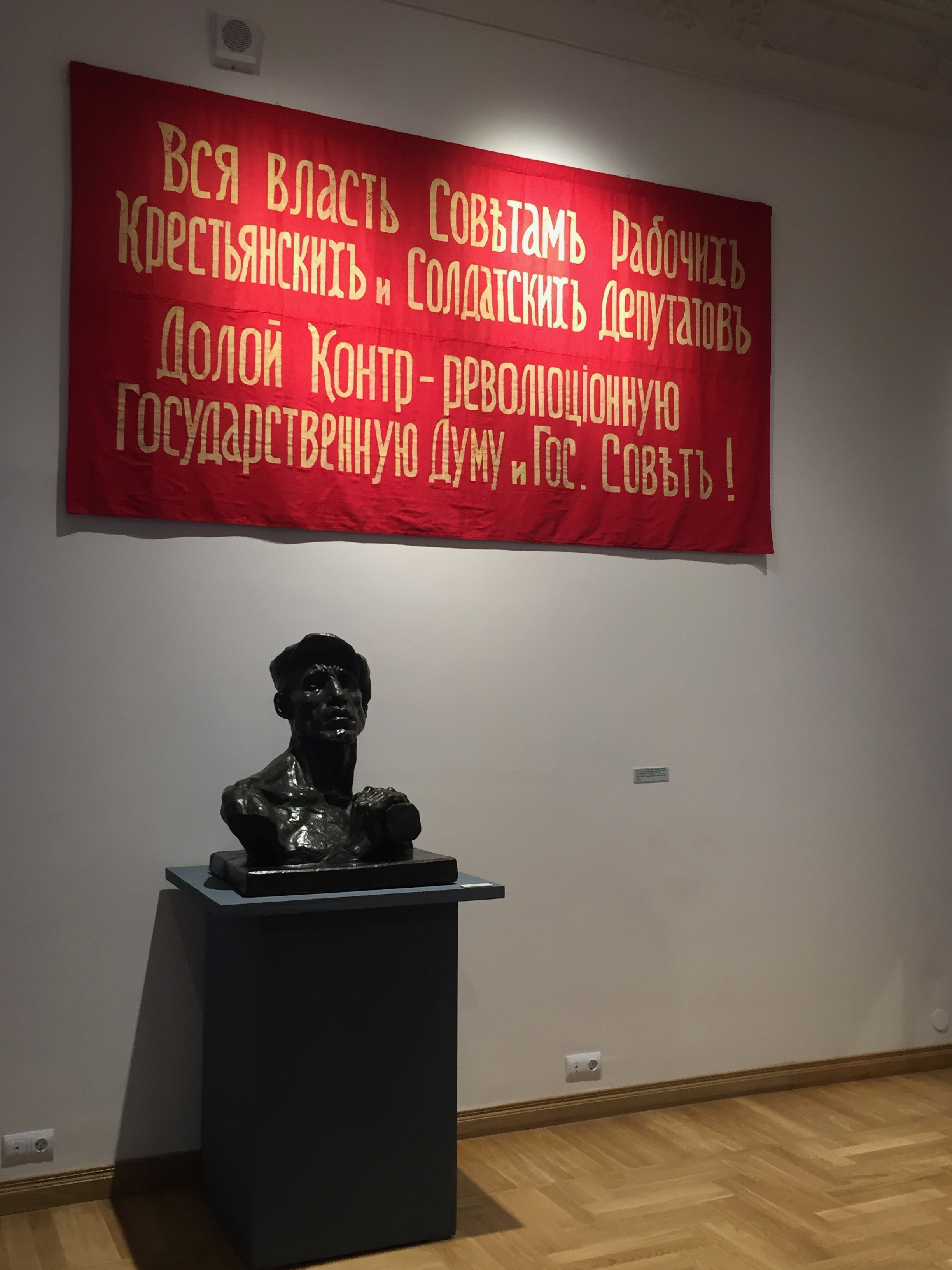

This museum’s “1917. The Code of Revolution” exhibition, created in cooperation with Russia’s Ministry of Culture, the Federal Archival Agency, and the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, presents little more than an overview of the political events of the period in question.

Other sides of life are hardly covered, except for charts showing the occupational structure of the country’s population at the beginning of the 20th century, as well as its gender, ethnic, social and confessional composition. There is also a brief section dedicated to the early Soviet regime’s relationship to the Orthodox Church, which, considering that the latter for a long time was a constituent part of the state, should also be viewed as a political matter.

Notably, while including in the ‘code’ of 1917 the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, the revolutionary events of 1905-1907, the First World War, and the February and October revolutions themselves (which is significant, for many projects reduce the events of 1917 to the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks), the exhibition completely disregards the Civil War that followed the October events. There is only one hint at it, made in the form of a 1920 Bolshevik caricature poster showing Alexander Kolchak, a head of the White movement, as an alcoholic hungry for power, blood and money and entitled “Every tenth worker and peasant should be shot down”.

This reductionism can hardly be accounted for by Russians’ lack of interest in the events of 1917. Rather, it signifies one important point: the current Russian regime cannot decide how to position itself in relation to 1917. It seeks to be a successor at once to the Soviet state and to the Russian empire; a victor of World War Two, which is used as the foundation for today’s memory politics, and yet a “spiritual counterbalance” to the West; a modernized secular state and a continuator of the Orthodox tradition unbroken by the revolutions. Due to this succession chaos, the authorities would rather not discuss the events of 1917 at all, but in a situation when it is impossible to ignore the topic completely, they choose to talk about it selectively.

“Cai Guo-Qiang. October”

Perhaps, this is why non-Russians do a better job at thinking about and interpreting 1917, be it outside of the country (no exhibition in Russia could compete in scale and depth with “1917. Revolution. Russia and Europe” at the German Historical Museum in Berlin) or within it (“Cai Guo-Qiang. October” at the Pushkin Museum). Although limited to the October revolution, the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s installations nevertheless present an exemplary reflection on 1917.

Towering in the museum’s front yard, his Autumn is a majestic construction made of old cradles and cribs, from which birch trees are growing; as time passes, their leaves are turning yellow and will unavoidably fall off. The installation is thus a powerful reflection on the inevitable autumn — or fall — of any utopia. Inside the museum, the work of memory continues in several other artworks. Land is a field of straw covering the floor of the museum’s White Room, with strange crop circles in the middle. Reflected in the large mirror above, the crop circles become the hammer, sickle and five-pointed stars. Prompting the viewer to think about the destruction of Russian farming in the course of collectivisation, as well as about consequences of the revolution more generally, Land is flanked by two other artworks, the giant 20-meter-long “gunpowder paintings” River and Garden. These paintings are in fact only the end result of performances during which photographs from the last one hundred years of Russian history, as well as images of revolutionary and Soviet posters, were covered with gunpowder and blown up by the artist in the presence of Muscovites.

As the cultural historian Alexander Etkind writes in the exhibition’s catalogue: “Commemorating the past and parting with it in a heavenly funeral feast, the explosive art of Cai Guo-Qiang opens up the way to our unknown century”. In other words, the exhibition at the Pushkin Museum is one artist’s attempt to bring the Russian revolution to an end. The Chinese emigrant Cai Guo-Qiang, whose life in China was largely defined by the revolutionary events of 1917 and who, upon leaving his home country, was unable to abandon his past there, through this memory work strives to take himself — and all of us — into the future.

“Someone 1917”

Why cannot we see examples of such memory work in other Russian museums? One of the reasons is that the exhibition at the Pushkin Museum uses the language of contemporary art, which brings a more fluid, complex understanding and is therefore less prone to authoritarian state control.

In “Someone 1917”, the Tretyakov Gallery also uses the language of fine art to discuss the revolutions, but, not being complexly “contemporary”, this language is easier to understand — and therefore requires more discursive framing. Although its goal is ‘to abandon the stale stereotypes [about 1917], and approach the understanding of the complex picture of the most important period in Russia’s spiritual life’ by looking at how differently Russian artists related to the revolutionary events, the exhibition — perhaps inadvertently — keeps reminding the viewer of the horrors that any revolution brings. Even its title, “Someone 1917”, derives from the writer Velimir Khlebnikov’s speculations on the ascent and decline of various states published in the 1912 anthology A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, where Khlebnikov prophetically implied that something dreadful would happen to Russia in 1917.

Presenting works of art mostly from 1916-1918, the show is divided into seven sections, and at least five of them to a greater or lesser degree condemn the revolution. The opening section, The Myths about the People, features Mikhail Nesterov’s 1916 painting Rus (The Soul of the People), in which Russia is presented in an archaically idyllic way. This painting is juxtaposed with works from Boris Grigoriev’s 1917-1918 Russia series and his 1921 painting Faces of Russia, predominantly critical of the Russian people, showing them acerbated, angry. The explication quotes the artist Alexandre Benois: “The nation will either show its glorified wisdom… or it will fall victim of its destructive power.” One of this section’s messages is clear: the Russians had been thought of as a holy people, but this was a myth: the people turned out to be a subversive force that, to use Benois’ phrase once again, became “the arbiter, not only of the Russian affairs, but of the fate of the entire world”.

Other sections of the exhibition follow suit: artists’ escapism from the “destructive tendencies of the time” is emphasised in the sections Away from This Reality!, the title of which speaks for itself; Artist’s Workshop, which describes how artists secluded themselves in their studios and worked there undisturbed by the revolution; and The Faces of the Epoch, in which the crisis of the portrait genre is noted and which shows Nesterov’s famous Philosophers (featuring Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov) with a caption explaining that “In the grip of their ideas, concepts, and projects people do not notice the real life, shut themselves off from it, and this, in essence, becomes the main mental contradiction of the epoch”. Curiously, even the section The New World Utopia, which by all odds should be discussing the great utopian ideas, instead underlines the fact that before 1917 non-figurative art ‘had no more than twenty supporters’ and yet this “absolute minority” “heralded revolutionary ideas and aspirations”.

This is not untrue, of course. But such an emphasis rhymes with emphases made in the exhibition “1917. The Code of Revolution”: accentuating every now and then that Marxist groups in the turn-of-the-century Russia were mostly comprised of intelligentsia, that Bolsheviks were initially a small group of radicals without any popular support, that the oppositional movement ignored the concessions made by the tsar in 1905 and consequently led the country to the bloody events of 1917 — all of this flattens the image of the revolutions, simplifies it. An example of selective remembrance, this treatment of 1917 serves to be little more than an illustration of “a national disaster” brought on by revolutionary events, to use an expression of Andrey Sorokin, director of the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, who introduces the exhibition catalogue. As Sorokin symptomatically asks in his address: “Why did Russian citizens and all the political and public organizations, who meant to promote people’s interests, fail to find a less traumatizing solution for the burning issues” that Russian society was then facing?

While Cai Guo-Qiang’s exhibition at the Pushkin Museum, uniting the personal with the universal, the Russian with the Chinese and the international, aims to be in its memory work as multidimensional and as comprehensive as possible, the other two exhibitions limit the events of 1917 to a catastrophic collapse and a failure of the state provoked by a group of intellectual extremists.

Has the revolution ended?

The 100th anniversary of 1917 has clearly shown that Russians still cannot make sense of the revolutions. Why? Perhaps because the Russian revolution is not over yet. If it does not belong to the realm of the past, it is understandable why neither a distanced look nor profound reflection on it from within the country are possible. This could also partly explain why the Russian regime, immersed in its succession chaos, is so reluctant to discuss 1917: though rooting itself in the victory in WWII, it wants nothing to do with the Bolsheviks and their initial idea of a “permanent revolution”. Hence, the authorities might not have fear of a revolution, as some commentators have pointed out, but they certainly do not want to actualise in collective memory the revolution as a phenomenon.

Memory is always connected to the present. In fact, it often says as much about today as about yesterday. The exhibitions at the Tretyakov Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary History of Russia, however, talk primarily about the present using the context of the past. Consider one last example: “The main reason for the defeat in the [Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905] was the revolution that broke out in Russia. The Russian opposition community assumed an expressly defeatist attitude”. Condemning the phenomenon of revolution itself, this phrase from one of the explications of “1917. The Code of Revolution” without hesitation uses the vocabulary of contemporary Russian politics.

A saying popular in the post-1945 Russia goes: “Anything but war!”. The anniversary exhibitions at the Tretyakov Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary History of Russia, it seems, transform it into “Anything but revolution!”. In effect, these exhibitions are less about giving a glimpse of “someone 1917” and more about frightening visitors with an imaginary “someone 2017”. Someone who, given too much intellectual freedom and too little vigilance of the authorities, will make Russia revolutionary again.

Read the essay in German on Russland-Analysen.