On the Flattening of the Earth and Other Realised Dreams

A Review of the Exhibition

On New Thinking and Other Forgotten Dreams

Secession, Vienna, 1 December 2023 — 25 February 2024

On the Flattening of the Earth and Other Realised Dreams

“Is this why this country existed—to invent crazy ideas and try to embody them?” Anna Titova asks in an interview with Maria Lind, reflecting on the Soviet Union. This question can also be applied to Titova’s and Stas Shuripa’s joint exhibition “On New Thinking and Other Forgotten Dreams”, currently on view at the Secession. In this review, I examine the tension—and ultimately the imbalance—between the artists’ ideas and their material embodiment.

The investigation of “crazy ideas” lies at the core of the Agency of Singular Investigations (ASI), founded by Titova and Shuripa shortly after the occupation of Crimea in 2014. ASI defines its mission as the “elucidation of the specific features of the current historical moment, and the possibilities and impacts of constructing reality through images and narratives.” Their practice relies on found documents, fictive archives, and speculative storytelling. After february 2022 the artists relocated to France and were subsequently invited to Vienna for an MQ residency and an exhibition at the Secession. The present show constitutes the first chapter of a larger project, “The Park of Mind Revolutions”, which asks how society has moved, over the past thirty-five years, from the hopeful ideals of perestroika and “new thinking” to today’s grim political and psychological condition.

Agency of Singular Investigations, On New Thinking And Other Forgotten Dreams, Exhibition view, Secession 2023, Foto: Lisa Rastl

A Mysterious Laboratory

To encounter the exhibition, visitors must climb the winding staircase of the Secession to the small graphic cabinet, transformed into a quasi-scientific laboratory. Inside, a yellowish aquarium bubbles quietly; a gas cylinder stands nearby; a large schematic diagram covers the wall. Together, these elements produce an atmosphere of suspended expectation. Objects appear to hover and invite engagement: a flat Dibond figure hangs from the ceiling by a string; a gas tube rises from the cylinder, traces the ceiling, and descends into the aquarium; unstable wooden pedestals with thin, asymmetrical legs support heavy plates assembled from mismatched parts, like insoluble puzzles. This pervasive sense of floating is interrupted only by the gas tank, which stands heavily on the floor, grounding the otherwise airborne constellation.

ASI presents six objects in the installation, yet a seventh element—less obvious but equally present—is the exhibition text. It explains the context and conceptual framework of the works, but its connection to the objects remains opaque. Reading it feels akin to watching a nature documentary that introduces numerous fascinating species without dwelling on any of them long enough to establish specificity. We are told, for instance, that a blue carpet represents Grigoriy Zamzin, the narrative’s main character. While intriguing, this claim remains abstract: Zamzin exists only in the text, while the carpet exists only on the floor, and their relationship is never materially articulated.

This gap raises both theoretical and ethical questions. How much explanation should art provide? How should text and image relate? And, given the artists’ position as representatives of contemporary Russian art within a European institution during an ongoing war, is a deliberate lack of clarity defensible? In an interview with Alexandra Markl, ASI state that the audience is invited to form its own interpretations. Yet such openness presupposes a shared context. Without it, this invitation risks becoming either a utopian fantasy of the “ideal viewer” or an act of negligence that leaves the audience without orientation or care. While the initial impression of the exhibition is enigmatic and intriguing, what follows is closer to confusion.

Works and Their Disjunctions

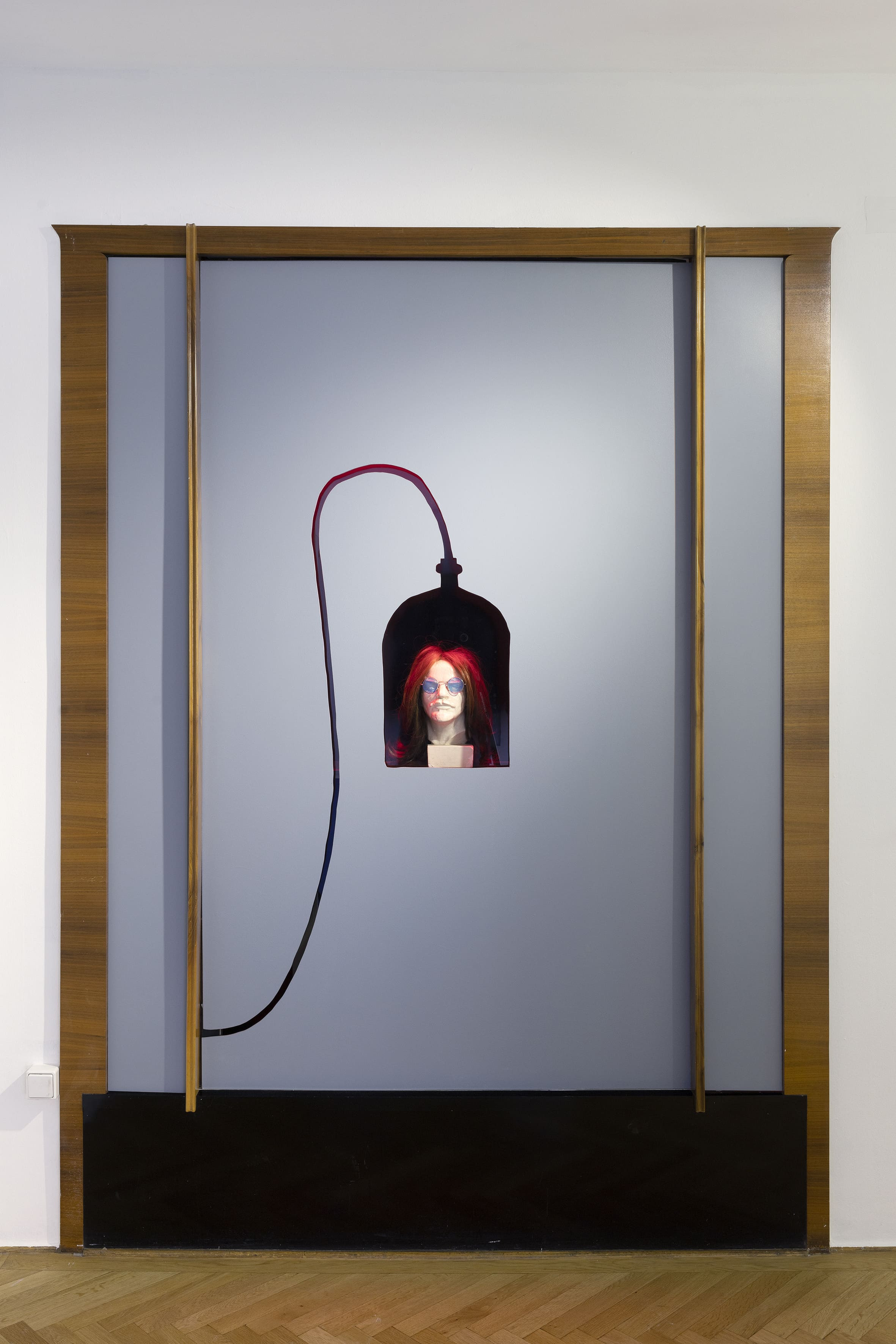

Lennon–Lenin (2023)

Located on the staircase in a glazed niche, this work consists of a bust of Lenin wearing John Lennon’s glasses and wig, illuminated by red light and encased like a specimen in a flask. The merging of two iconic figures of “ideas” functions as an overt gesture of retrospection. It illustrates—perhaps too literally—the exhibition’s central question: what remains of past hopes, and how did the trajectory from Gorbachev’s “new thinking” lead to Putin’s “we can repeat”?

Agency of Singular Investigations, On New Thinking And Other Forgotten Dreams, Secession 2023, Foto: Lisa Rastl

Lavender Mist of History (2023)

Facing the bust is a large wallpaper print featuring a diagram that connects names, events, and concepts from recent Russian history. The title references Jackson Pollock’s "Lavender Mist", despite the absence of lavender hues. As Shuripa explains, the intention is to represent time not as a linear progression but as an abstract mass moving toward us. While the diagram undoubtedly gestures toward collective memory, it lacks any discernible personal stance. Printed on wallpaper, the scheme emphasizes reproducibility rather than investigation. The viewer either recognizes isolated terms without grasping their relations or traces connections without understanding the references. This experience recalls Venichka from Venedikt Erofeev’s “Moscow-Petushki”, whose intoxicated clarity dissolves into confusion. The work simultaneously opens and forecloses possibilities of comprehension.

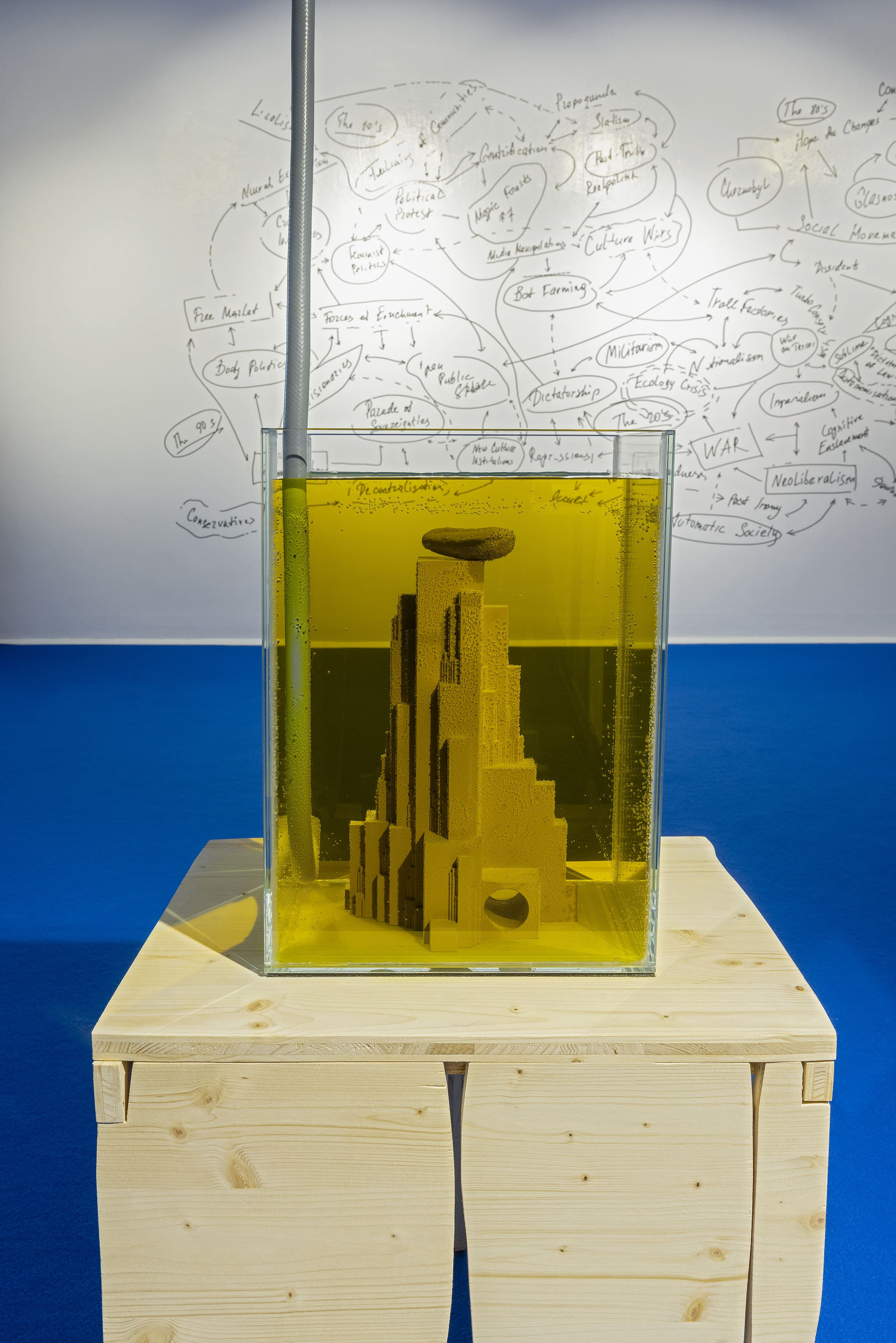

Descend (In Conversation with Grigoriy) (2023)

Adjacent to the diagram stands an aquarium filled with yellow liquid, containing a model of Kazimir Malevich’s "Arkhitekton" topped by a pickle, connected via tubing to a CO₂ tank. According to the text, the work transcribes a dialogue between the pickle—a “conserved witness”—and Grigoriy Zamzin, a worker involved in a Soviet project to reverse Siberian rivers, who also fantasizes about flattening the Earth and producing black holes. Yet Grigoriy is absent from the aquarium. The dialogue’s impossibility is thus literalized; perhaps it has already collapsed into a black hole.

Agency of Singular Investigations, On New Thinking And Other Forgotten Dreams, Secession 2023, Foto: Lisa Rastl

Grigoriy Zamzin (2023)

Zamzin himself is said to be represented by a blue carpet spread across the floor. The figure recalls the “little man” of Russian literature—socially and existentially constrained. The carpet is everywhere and nowhere, supporting bodies while remaining anonymous. Associations range from laboratory flooring to political symbolism. Zamzin’s dissolution into the ground suggests the flattening force of history upon individual lives—an interpretation that, however, remains fragile without textual guidance.

Dance (2023)

A blurred dibond silhouette of a woman arrested during anti-war protests hangs above the carpet. Her pose evokes both a victim and a frenzied dancer from the 1990s. The lighting casts double shadows: on the floor, a bird with outstretched wings; on the wall, a figure with raised hands. These shifting images suggest flight, surrender, and execution simultaneously. Yet the material execution—smooth, flat, and commercial—undermines this ambiguity, lending the figure the quality of a supermarket display.

Agency of Singular Investigations, On New Thinking And Other Forgotten Dreams, Secession 2023, Foto: Lisa Rastl

Towards the New Flat Earth (2023)

The final work combines a model of El Lissitzky’s "Lenin Tribune" with illustrations by Vladimir Konashevich, which ASI propose as inspirations for underground Soviet installations. The piece is meant to reflect the failure of revolutionary visions and the succession of unrealized projects. While the overlay of drawings disrupts the Tribune’s diagonal dynamism, the object’s polished, toy-like finish reinforces a sense of simulation rather than critical tension.

Dystopia versus Utopia

Throughout the exhibition, gaps between narrative explanation and material form remain unresolved. Fiction functions more effectively in the textual register than in the spatial one. This narrative strategy recalls the Soviet underground tradition, most notably Ilya Kabakov’s "The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment". Kabakov’s installation constructs a self-contained utopia, complete with evidence of an impossible event. ASI, by contrast, presents a dystopia: projects are unrealized, actions reduced to speculation. History becomes abstraction; models resemble toys; witnesses turn into pickled vegetables; protagonists dissolve into carpets and mannequins. Nothing is what it claims to be.

The audience’s hope to understand the Russian condition mirrors the artists’ hope to be understood—both remain utopian. The exhibition itself responds with a dystopian gesture: an installation that resists sense-making without its accompanying text. Like Zamzin’s dream of a flat Earth, it simulates rather than realizes its ambitions. If Kabakov fulfilled his character’s desire, ASI stand beside their “little men,” imagining grand ideas without embodying them.

Perhaps this is the exhibition’s paradoxical strength: it stages the impossibility of realization itself. Objects hover, bubble, and drift; viewers pass through. Meaning remains elusive. The work invites us to dwell in the illusion of perception and the failure to construct—or change—real worlds.

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, 1985