The Exquisite Corpse of Modernism

Andrey Shental is an artist and a critic. He lives in Moscow. You can find more of his work on andreyshental.com.

As part of the project “Political Dimensions of Cultural Praxis and Knowledge Production”, we are publishing Andrey’s essay, where he describes the history of conflicting ideological interpretations of modernist artistic techniques, mainly collage and montage. And explains why in the multipolar world of total post-irony and in absence of innately “left” and “right” aesthetics we need the nuanced and politically engaged art critique.

Read more about the series — https://syg.ma/@sygma/political-dimensions-of-cultural-praxis-and-knowledge-production

Текст на русском можно прочитать по ссылке — https://syg.ma/@sygma/izyskannyi-trup-modiernizma

Montage gluing and Manichean criticism

Traditionally, progressive modernist criticism praised artistic techniques of montage that disrupted the integrity of a work of art. Ironic subversion, critical negation, and dialectical vivisection of the image were used by artists to challenge the prevailing canon, to liberate the public from the shrouded gaze, and hence to shake the existing capitalist world order. They were opposed by conservative notions of an organic work of art that inherits the authority of the artistic tradition, an unbroken natural and often archaic order, and evolutionarily determined constants of perception. The key dichotomy for Western modernity—between freedom and subordination, emancipation and subjugation—is revealed in the dispute between these two aesthetics.

In the 2010s, in the wake of the global neo-conservative turn, progressive criticism was dealt an unexpected blow in the back: all those tropes and mechanisms that it had long defended and credited to itself were seized by right-wing sensibilities [1]. For example, the critic Marc Goertzen argues that “the new Right has appropriated these tools from earlier generations of Leftist cultural warriors — and configured them for a new battlefield by embracing anonymous social media technologies” [2]. Similarly, publicist Angela Nagle laments that familiar avant-garde tactics, such as transgression and subversion, have come to be used in art and popular culture by the right against the left, rather than vice versa, as they were in the 1970s [3].

To this one could argue that there is nothing new in such appropriation. Even the historical avant-garde of the early twentieth century—the Russian and Italian futurisms, for example—could serve as one ideological disposition as the opposite. Nevertheless, the problem of the consistency of artistic tradition and the possession of one’s own arsenal of means has always preoccupied critics and continues to do so. In this text, I will try to explain how this or that aesthetics could be a weapon in the hands of a particular political side and what are the prospects for its resetting in a “post-critical” situation.

From left to right

The philosophers of the Frankfurt School—whose ideas permeated post-war Western universities and academies—believed that in contemporary capitalism political resistance should shift from the base (economic relations) to the superstructure (i.e. culture and art). A follower of their ideas, Peter Bürger, a few decades after the publication of his classic Theory of the Avant-garde (1974), confessed that in the light of the defeat of the 1968 revolution he “transferred, without being conscious of it, utopian aspirations from a society in which they could clearly not be realized to theory” [4]. In post-war Western Europe and North America, it is precisely visual culture—instead of factories and tribunes—that has become the new arena of revolutionary struggle, and art criticism has taken on the role of party leader, who in the variety of aesthetic phenomena must recognize signs of regression among progressive elements in order to revolutionize the public. Within the leftist consensus of contemporary art—and contemporary art is leftist by definition—this system has functioned quite successfully. After all, the enemy, clothed in historical paintings, was easily recognizable and hopelessly archaic.

The new right-wing turn was unexpected because against the intellectual establishment of the left, which the former called “cultural Marxism,” it turned the latter’s own weapons. The right turn shifted the emphasis from the productive forces (Marx’s means of production) to the sphere of visual production, ironically playing with the term “memes of production.” This war of memes against montage certainly had other reasons itself, stemming from the expansion of digital technology. Since in contemporary politically correct culture the expression of extreme right-wing views is only possible anonymously, i.e. via the Internet, the mediation of information by screens contributed to its visualization [5]. In addition, a rudimentary PC function such as copy paste, and later various smartphone apps that allow you to create complex collages with the swipe of a finger, have democratized visual culture as a whole. The murderous irony of the photomontages of anti-fascist John Heartfield or Alexander Zhitomirsky, an artist bypassed by Western art critics, has been replaced by anonymous memes and 4chan or nihilistic demotivators of [popular Russian social network] VKontakte group sections.

Thus, according to this narrative, montage techniques, the invention of which was attributed to anti-bourgeois artists, filmmakers and theatrical directors at the beginning of the 20th century, followed a looping path. First, they emigrated from the realm of art to the realm of memes and stickerpacks circulating in social networks and messengers, etc. Then, from the mass and anonymous online culture, they moved back into so-called post-internet art, occupying the traditional means of expression — painting, sculpture, installation and video art. And finally, through various aggregators of images from gallery art, they have returned to smartphone screens, once again becoming a mass and dispersed phenomenon. Much has been written about the genealogy of this right-wing aesthetic as well as its connection to reactionary ideology (alt-right, white supremacism, right-wing accelerationism, neoreaction, etc.) by magazines like Texte zur Kunst, Springerin and above all Art Monthly [6]. I will only mention, schematically, its distinctive qualities: visual omnivorousness, ideological ambivalence and emasculated experimentalism.

Although many opponents of this sensibility have repeatedly stressed that appropriated methods and techniques cannot be bad per se, one can easily detect a resentment behind them due to the loss of a monopoly on means of expression. In her most consistent and devastating critique of the nascent fascist sensibility of post-internet art, as well as music and fashion, Larne Abse Gogarty attempts to outline its clear aesthetic coordinates. In particular she identifies a mixture of the ancient and the futuristic, an appeal to the authority of tradition, behind which she sees a tendency towards subordination and an acceptance of the status quo as inevitable [7]. However, within this holistic and easily recognizable aesthetic, Gogarty distinguishes two opposing trends. The first is a “flat unmediated aspirational nihilistic strain,” which rests on a totalizing view of the world where meaning, time and history are bankrupt and the social dimension is absent. The second, an “excessive particularising metamorphic strain,” [8] by contrast, follows the principles of mediation, relationality and self-reflexivity.

If to the first group—which, in her opinion, is vulnerable to a fascist interpretation—she includes the artist Katja Novitskova, Simon Denny, Timur Si-Qin, the musician Holly Herndon and the clothing brand Vetements, then to the second critical trend she lists Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, Sondra Perry, NON WORLDWIDE and the collective Women’s History Museum. The public, which is familiar with the work of these authors, might be surprised to see such arbitrary polarization as subjective and based purely on personal taste. For example, the blockchain praiser Denny may well be interpreted as a left-wing artist critical of financial capitalism, etc. As I see it, this inconsistency and ambiguity is possible because such ideological demarcations come from idealistic attitudes inherited from the American critical school. In particular, while being faithful to montage values—the techniques of Soviet Constructivism and German anti-bourgeois Dadaism—Gogarty believes that memes should be expropriated from the right. The idealization of montage glues that undermine the holism of the flat patriarchal tradition has a long philosophical genealogy.

Collage with a capital letter C [9]

Indeed, collage, which collides conflicting surfaces without hiding their seams in any way, can be considered a paradigmatic technique of critical art. It is a “metatrope”—through which we can look at similar techniques in other expressive media: for example, montage in film, assemblage in sculpture, the effect of defamiliarization [estrangement] in theatre, construction in objects, fidelity to material in architecture. Just as the intellectual differs from the ordinary person in their capacity for introspection, so progressive art differs from bad art in its immanent self-criticism.

This apologetics is based on a fundamental understanding of modernism as a critical procedure, which genealogically goes back to the Enlightenment. As we know, according to Immanuel Kant, the task of philosophy is first and foremost to methodically examine its own foundations, possibilities and limitations. And precisely because of this, it differs from religion, which only blindly reproduces the postulates of scripture. The American critic Clement Greenberg, whose name today is associated exclusively with doctrinaire formalism, was in fact a consistent adherent of this noble idea to the end of his days. In his classic text “Modernist Painting” (1961) he wrote: “the essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence” [10].

For Greenberg, “the areas of competence” were limited to the boundaries between means of expression or mediums. He defined painting negatively by the rejection of the subject matter of literature or the depth of sculpture. Significantly, the critic himself exalted the collage technique, invented by either Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso, and dedicated to it an essay of the same title in 1959. His interpretation of this technique is very specific and dictated by his master idea—the historical justification of painting as a medium, that follows a successive “flattening,” that is, is getting rid of illusory volume. While other critics saw the use of newspaper clippings or textures as introducing an element of “reality” into the abstraction of analytical cubism, for the formalist critic they served not as referents of external reality, deceiving the viewer, but rather as “tokens” (like the author’s signature at the bottom of the canvas), revealing the conventionality of both pictorial and non-pictorial elements. The clash of these elements is described as a tense battle scene of conflicting origins, where one or the other imaginary warrior defeats its opponent. As a result of the overlaps, superimpositions and crossroads, flatness wins out over the illusiveness of depth.

Certainly, such “purism” was unacceptable for the analysis of the new art that had replaced high modernism. The critics of the magazine October (founded in 1976), who are generally considered to have dissociated themselves from Greenberg, did not take his division of art into mediums seriously, for it did not correlate with the new artistic practices: object, installation, performance, etc. However, their notions of the value of this or that work of art largely grew out of Greenberg’s ideas, inheriting the ideals of Enlightenment.

In his seminal text “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression” (1981), Benjamin Buchloh, one of the most influential contemporary critics, attempted to dissociate critical art from the neo-expressionism and transavant-garde of the 1980s. In fact, his text, to which Gogarty not coincidentally alludes in her exposure of the post-internet aesthetics, presents a panegyric to the modernist collage and a merciless injection of historicist imagery, comparing the contemporary to the author situation with a return to the order of the 1930s. Thus while “the modernist collage, in which various fragments and materials of experience are laid bare, revealed as fissures, voids, unresolvable contradictions, irreconcilable particularizations,” […] “the historicist image pursues the opposite aim: that of synthesis, of the illusory creation of a unity and totality which conceals its historical determination and conditioned particularly” []. Thus “this appearance of a unified pictorial representation, homogeneous in mode, material, and style, is treacherous, supplying as it does aesthetic pleasure as false consciousness,” while the modernist collage “provides the viewer with perceptual clues to all its material, procedural, formal, and ideological qualities […] which therefore gives the viewer an experience of increased presence and autonomy of the self” [11].

Three years later, in another of his famous essays, “From Faktura to Factography,” also referring to the termidor of the 1930s, Buchloh complicates this polarization by examining how the photomontage techniques of El Lissitzky, Gustav Klucis and others were mirrored by Italian fascism (particularly Giuseppe Terragni) and the techniques of Sergei Eisenstein by Leni Riefenstahl. From techniques that broadened the political consciousness of the masses, they became a tool of their totalitarian repression. At the same time, the critic stresses that such appropriation is “by no means simply the case of an available formal strategy being refurbished with a new political and ideological meaning” [12]. In essence, Buchloh is staging a battle scene similar to Greenberg’s, trying to draw distinctions within montage — a dialectical (leftist) one characterized by discontinuity, and a unifying and continual (right-wing) one that leads to monumentalization.

The distinction between the two approaches follows a binary logic: the right-wing position defines “ontologically” immutable and indisputable criteria for the existence of a painting or other medium. It creates works that are seamlessly fused, where different relationships are hierarchical and visual conventions gain historical authenticity and even biological legitimacy. The contemporary neo-Darwinist aesthetic to which some post-internet artists refer is here linked to the very term “meme,” borrowed from evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. The leftist position, on the other hand, proceeds from a historical conventionality where all characteristics are relative and socially conditioned. Buchloh, like many other October authors, tries to ground his aesthetic preferences in real history, highlighting its recurring patterns of revolutionary upheaval and conservative backlash. Collage thinking is common to the historical avant-garde of the 1920s and the neo-vanguard of the 1960s, while wholeness is common to the return to order / retour a l’ordre of the 1930s or Reagan’s 1980s. With some reservations, contemporary critics also reproduce this “return of the displaced,” linking post-internet art with the neo-reaction of the 2010s.

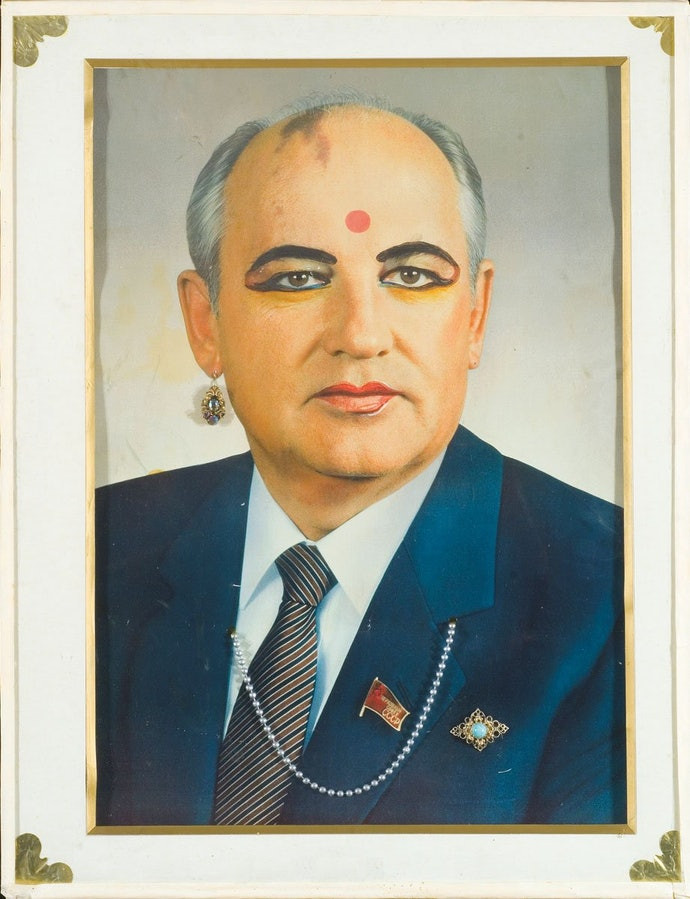

But this fetishization of montage glues, of the heterogeneous and non-self-identical work of art, also has deeper roots—in the projection of the object onto the person herself. As Theodor Adorno wrote, the work of art is a quasi-subject, that is, a semi-equivalent to the individual in capitalist society. Indeed, the leftist American intellectual tradition—which inherits ideas from Lacanian psychoanalysis and Foucauldian theories of the subject—has emigrated from France across the Atlantic. According to social constructivism, based on these theories, the subject is not a given biological entity once and for all, but is constructed at the intersection of gender, class, ethnicity, race, etc. This view certainly appeals to progressive critics because it promises emancipation and freedom of self-determination. The revolutionary struggle, transferred from the base to the superstructure, accordingly became a struggle for the recipient to overcome the so-called “false consciousness.” The subjects of the October school are always incomplete, fragmented, split and constructed, just like the collage itself. A successful example here could be the work of Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, where the gaps and seams of his techniques—both performance and collage— correspond to the performativity of gender itself. Thus the Kantian question of the subject’s freedom of self-determination—which includes gender identification—is finally presented to the viewer.

One way or another, in this confrontation between right-wing and left-wing interpretations of modernist and contemporary art, American art critics have defended a certain sensibility by retrospectively adjusting the entire history of Western art to their ideals. And no matter how convincing the arguments of Buchloh, Hal Foster and others may be, if we rise from the level of partisan confrontation between the American and Western European context, to the geopolitical level, their victory proves to be only relative.

Like the authors of October, the Soviet Marxist critic Mikhail Lifshitz, who wrote his major critical texts in the 1960s, similarly tried to ground his personal aesthetic orientation in a political program. By changing the plus sign to minus, he no less convincingly divorced socialism from modernism. In his book “The Crisis of Ugliness” (1968) the deformation and destruction of the object by Cubists, which was to reveal an objectified reality to the gaze, in his interpretation, on the contrary, dehumanizes the spectator and reduces human to a thing. Contradictions and particularities, which in Buchloh’s opinion constitute the value of collage technique, are seen by Lifshitz as monstrous debris of the visible world.

This contradiction appears particularly rendered in the key question of the freedom of the subject, where both positions appear to be sides of the same coin. The subject of realistic pictorial art, which Buchloh opposed, and the subject of modernism, which opposed Lifshitz, are equally enslaved, and the denunciatory rhetoric of both critics strikingly coincides. If, in the first case, the “self-denial of morbid subjectivity takes place in favor of the most flat system of patriarchal, ancient ideas of stick discipline and everything that Germans call Zucht” [13]. Then, in the second case, a return to the language of representation appeals to “eternal” or ancient systems of order (the law of the tribe, the authority of history, the paternal origin of the master, etc.) and affirms them, which is characteristic of the syndrome of authoritarianism.

The return of the Eastern European sensibility to this never actually happened dispute shows that the correlation between the structure of human subjectivity and the artistic medium, between historical and political conjuncture and the set of aesthetic characteristics, turns out to be more accidental than necessary. Not only may particular tendencies be taken as reactionary or progressive, but whole aesthetic programs may also become bargaining chips in the cold war of critical writing. In this case, both sides are heirs to the Modernity, only that American criticism elevated the reflective and rational to the status of aesthetics, while Soviet criticism saw such self-reflection as a “counter-Enlightenment,” where rationality itself became irrational. From this we can draw a quite simple conclusion: modernism itself—like the now infamous Pepe the Frog—is politically neutral. The views of its critics can be called to be hypostatic, i.e. transforming of abstract entities into actually existing things.

The voice of criticism

Attempts to articulate a political programme through aesthetics are based on an almost psychoanalytic transference — the projection of one’s own speech onto an inanimate image. The resulting tautology — the vesting of a mute object with a voice — is often signified through the metaphor of ventriloquism. Art historian James Heffernan, for example, describes analysis as a “the painting soliloquy or confession, so that the painting’s ‘truth’ is a story constructed by the critic and ventriloquistically voiced by the silent work of art” [14]. In this way, the political position—from the critic’s subjective point of view—is objectified, i.e. postulated as an objective fact of reality. Sometimes it is confirmed by the very logic of the historical process, so that any arbitrary artistic gesture solidifies into an objective necessity (remember the Greenbergian narrative of the “flattening” of art). And if we accept Alain Badiou’s view of art as a procedure of truth, then art is the final judge, confirming the position of the art historian as the source of ultimate truth.

Returning to contemporary right-wing aesthetics, we find that the question of ventriloquism here is more acute than ever. Discussing the 9th Berlin Biennial Present in Drag (2016), the Athens Biennial ANTI (2018) and other projects representing “art of the cynical reason,” many authors have noted the serious limitations of the mimicry tactics practiced by post-internet artists. Identifying with neoliberal capitalism — for example, imitating corporations in order to criticize them — can prove indistinguishable from glorifying it. Dorian Batycka has identified three popular tactics of right-wing aesthetics: “parafiction” (presenting fiction as fact), taking a position of the third (a viewpoint that denies both communism and capitalism) and “over-identification” (over-identifying with ideas antithetical to one’s own ideology) [15]. They all speak not of a rejection of straightforward statement in favor of allegory and plurality of meanings, but of a complete avoidance of responsibility for what is said.

Of course, there is nothing new in this renegation, since the denial of differences in political positions as obsolete is a well-known tactic of the right. Moreover, the second half of the last century gave rise to an overpowering phenomenon that until recently was commonly referred to as “postmodernism.” Its main characteristic was relativism of ideology and value, that seemed to have accustomed us to the constant mockery and quotation of others’ words to help us evade voicing and expressing our political position. Nevertheless, even within it, the critics of October magazine have managed to identify two “rival” aesthetic schemes: neoconservative and poststructuralist (critical) postmodernisms [16].

Contemporary right-wing sensibility exists in a different value and political paradigm, in a situation of not one but many “post:” post-truth, post-internet, post-irony, etc. The distinction between postirony and postmodern irony is best described by Wikipedia as the combination of cynical mockery and a new sincerity, “when something absurd is taken seriously, or when the seriousness or non-seriousness of the situation is not obvious” [17]. In other words, even when producing a radical statement or a transgressive gesture, the message of the speaker can be considered neither critical nor affirmative. It is precisely in this that the new art is akin to Internet memes: returning from gallery space back to online aggregators and instagram-feeds, its voice dissolves into a polyphony of visual noise.

This is all consistent with the state of art criticism. In recent decades, we have witnessed not only a shrinking public sphere and the dying out of the figure of the “public intellectual,” but also a parallel process of profanation of independent criticism—its transformation into a recommendation to visit, or at worst, a consultation for market investments. Criticism long ago abandoned its philosophical self-reflexive expressions in favour of what Hal Foster described as the “post-critical state” [18].

However, the arbitrary connections I have described between criticism and artistic practice should not at all invalidate the politicization of aesthetics. My position is precisely in the contrary. The changing of sides, revanchism, and promiscuity of certain artistic practices, the easiness with which artistic matter falls victim to the discourse, do not discredit criticism; it only endows it with more significance. Existing in a more complex context than a century or even a decade ago, it should not rely on the usual Manicheism of “right” and “left” aesthetics. Yet a nuanced critical orientation does not equal depoliticization, and politicization does not equal indoctrination. More than ever, art requires ventriloquism and the critical voice requires amplification.

As an example of an articulated position, the exhibition “The Alt-Right Complex — On Right-Wing Populism Online” (HMKV, 2019) [19] shows that appropriation is always a twofold process when properly conceptualized. In this ambiguous research project, curator Inke Arns presented an entire encyclopedia of right-wing slang, memes and personas, as well as works by contemporary artists who have critically conceptualized visual populism to a greater or lesser extent in order to increase media literacy. To illustrate my point, I will cite only the work of Jonas Staal, who analyses the films of Donald Trump’s ideologue Steve Bannon. Curiously, the far-right Bannon was inspired by the avant-garde director Sergei Eisenstein, the founder of radical montage techniques. In a sense, “The Alt-right Complex” is a degenerate art exhibition turned inside out, presenting right-wing visual culture as “bad” and its deconstruction by left-wing artists as good. This kind of double reflection — nuanced but not relativized — can be seen as a response to the nihilist principle of anything goes. The appropriators are appropriated.

Art of the 20th century has come a long way from doctrinaire formalism to agitation, propaganda, or actionism and art activism. As we know very well in the former East block countries, personal aesthetic preferences even physically repressed people. In the new coexistence of a multipolar world, when realism is not at all at odds with modernism, and even historical social realism is at peace with contemporary art, new distinctions and demarcations beyond simple binary oppositions are required. The proto-Indo-European root “krei,” which is at the root of the word “critique,” means to distinguish, and it is distinction that will restore critique to its enlightened role of liberating the subject.

References

[1] Opponents call this new aesthetic “nihilist,” “neoconservative,” “alt-right,” “rebellious,” “libertarian,” “accelerationist,” “populist.”

[2] Matt Goerzen, “Notes toward the memes of production.” Texte zur Kunst, no. 106, (June 2017), pp. 86-107.

[3] See: Angela Nagle. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan And Tumblr To Trump And The Alt-Right. London: Zero Books, 2017.

[4] Peter Bürger. “Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt to Answer Certain Critics of Theory of the Avant-Garde.” New Literary History, vol. 41, no. 4, (Autumn 2010), p. 699.

[5] Mike Wendling. Alt-Right: From 4Chan to the White House. Pluto Press, 2018, p. 10.

[6] Morgan Quaintance. “Right Shift.” Art Monthly, (2015).

Ana Teixeira Pinto. “Artwashing — On NRx and the Alt Right.” Texte zur Kunst, (2017).

Larne Abse Gogarty. “The Art Right.” Art Monthly, (2017).

[7] Larne Abse Gogarty. “Coherence and Complicity: On the Wholeness of Post-Internet Aest,” 2018.

[8] Ibid.

[9] When critics discuss modernist sensibility, for convenience they single out painting as a paradigmatic medium. Painting with a capital letter P is used as a convenient theoretical construct, which brackets the differences between other media of expression.

[10] Clement Greenberg. “Modernist Painting,” 1961.

[11] Benjamin Buchloh, “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting,” October, 16, (1981), pp. 39-68: 56.

[12] Benjamin Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October, 30, (1984), pp. 81-119: 110.

[13] Mikhail Lifshitz. The Crisis of Ugliness: From Cubism to Pop-Art, Ed. By David Riff. Boston, Leiden: Brill, 2019.

[14] Heffernan J.A.W. Cultivating Picturacy: Visual Art and Verbal Interventions. Waco: Baylor UP, 2006. p. 66.

[15] Dorian Batycka. “Is Accelerationism a Gateway Aesthetic to Fascism? On the Rise of Taboo in Contemporary Art.” Paletten, no. 319 (2020).

[16] Ibid, p. 640.

[17] According to Wikipedia page on post-irony.

[18] Hal Foster. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency. London: Verso, 2015.

[19] Dorian Batycka. “Entering the Echo Chamber of the Alt-Right.” Hypeallergic, (2019).