Staging Gaia. Theatre, Climate and a Shift in Awareness

The talk of Bruno Latour and Frédérique Aït-Touati with Thomas Oberender took place during preparations for the exhibition “Down to Earth” in 2020. It was published in the book “CHANGES. Berliner Festspiele 2012 — 2021” and can be purchased at Theater der Zeit.

Bruno Latour is a sociologist and philosopher, Frédérique Aït-Touati is a literary scholar and director, Thomas Oberender is a curator and author.

More about the work of Thomas Oberender. More about the work of Frédérique Aït-Touati.

Thomas Oberender: For us, Down to Earth is a “little organum” in the Brechtian sense — a practical tool, a guide for behavioural change. This comes very close to our intentions regarding the exhibition of the same name in Gropius Bau. Considering our collaboration, I am very interested in your and Frédérique’s fascination with theatre. In your book, you keep speaking in theatre metaphors. You write: “Today, the decor, the wings, the background, the whole building have come on stage and are competing with the actors for the principal role.” [1] I like this idea very much: today, conflicts are no longer bound to the human sphere but can also take place within the realm of all the things that inhabit a stage — thereby enabling those things to take on agency of their own. This idea reminds me of James Lovelock’s “systemic” perspective on the earth. His so-called Gaia Theory poses a change of world- view that is as fundamental as the one Galileo brought about approximately 400 years ago.

Bruno Latour: When Galileo Galilei turned his telescope towards the sky in 1609, he discovered mountains on the surface of the moon. Thus, the moon became another earth and earth a star among many others. With this act, he not only revolutionised the cosmic, but also the political and social order of his time. Four centuries later, the role and position of our planet have once again been turned upside down by new scientific discoveries which reveal our planet’s unexpected reactions to man- kind’s actions. Galileo taught us that the earth is in motion. The scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis discovered an earth which is “in motion” in a different sense: they describe a planet on which space and time are the products of living beings’ actions. They make us invent a new image of earth and a new understanding of the cosmos. And once again, the whole organisation of our society seems to be at stake. While in 1609 we had to accept the shocking revelation that “earth is in motion”, we must now come to terms with the even more shocking realisation that the earth is shaking und reacting to human activity — to a degree that calls all of our current projects to a halt and demands that we recalibrate our thinking.

TO: Over the past few years, you have created various productions and exhibitions on Lovelock and the theme of Gaia. I would like to talk with you about Brecht and his theatre, as his Life of Galileo poses an important point of reference for you. In your production “Moving Earths”, you use an American movie adaptation of the play from the year 1975 — a traditional costume film, practically the complete opposite of your idea of theatre.

BL: (laughs)

Frédérique Aït-Touati: You’re right! Bruno is very fond of this film. At first, I didn’t want to use it, precisely because it is so different from the kind of theatre I make. Of course, using this film creates tension: in our scenic demonstration, we use fiction like this movie as paradoxical “evidence”.

I would say that our experiment, although it’s formally different, is even more Brechtian than Brecht himself

TO: The staging of evidence has been part of Bruno’s work from early on, for instance in his book about Pasteur. In your essay When Non-Humans Enter the Stage, you express your interest in Bruno’s work as a director as well as in the ways scientists stage evidence. In Pandora’s Hope Bruno describes, among other things, Pasteur’s genius in creating a theatrical situation which helped make the evidence of his discovery of lactic acid fermentation visible to everyone. Brecht, too, strove to develop a “theatre of the scientific age”: in Brecht’s play, Galileo is 46 years old, his work is stagnating, and suddenly a young man brings him news of the invention of the telescope in the Netherlands. With this instrument, he can now make his new worldview visible to everyone. Brecht shows us Galileo as a great man, a loner and a genius. This differs from your work.

BL: This problem came up when I was castigated by Frédérique for wanting to draw a parallel between Galileo and Lovelock. She said: “This is ridiculous. In the 21st century, we cannot have this male-centred parallel between this great man Galileo and another great man from the 20th century.” So, my first draft attempting a parallel between the two had to be changed — also because the idea of Galileo as a loner in the 16th or 17th century was wrong. Rather, he was embedded in a particular scientific and social context which made it possible for him to emerge in the first place. We had to redistribute each character’s amount of text and connect the storyline to the scientist Lynn Margulis, who unfortunately died in 2011, in order to be able to re-associate it with Lovelock. He is now 101 years old…

FA: Brecht was a good starting point because he establishes a link between Galileo and the scientific age. In his Little Organum for the Theatre, he explains that he wants to make theatre for the scientific age. But it is precisely this type of cosmology and physics that is called into question by Lovelock and Margulis’s Gaia hypothesis. So, we needed to draw a parallel and a reversal at the same time. Bruno at some point said: “Ok, we need a new Brecht in order to tell the story of Lovelock. In telling the story of Galileo, Brecht links the cosmological revolution with the social upheaval of the 17th century. Now, we need a playwright to tell the story of Lovelock, the discovery of Gaia and its political consequences, to draw a link between the change in the cosmological order and the change in the political order.” The Galileo/Lovelock parallel is an intuition, which is already a theatrical situation, in a way: Galileo looks up at the sky with his telescope and discovers that earth is a planet among others. Lovelock imagines a Martian pointing his hypersensitive instruments towards earth and discovering that the earth is unique. The problem is that Brecht — following a long tradition in the history of science — has made Galileo into the heroic figure of a scientist opening the gates for modernity. But we can’t tell this kind of story with a sole male scientist as the hero anymore. Bruno’s book on Pasteur is a perfect critique of this narrative. Especially because the history of the discovery of Gaia is much more complex, interesting and collective! That was one reason why we couldn’t simply turn Life of Galileo into “Life of Lovelock”.

BL: We don’t have heroes anymore, but we have Gaia.

TO: Is Gaia a female character?

BL: She is female, but mainly she is a mythical character and a fairly big one. The idea was not to reuse the great-man- story but the means of theatre in order to create a feeling for the novelty of Gaia. It was Frédérique’s idea to actually have the presence of Gaia visible on stage. I came to this through the dramatisation of the concept, which I was always interested in. I have been teaching first-year students for 40 years. If you teach first-years you cannot get too complicated, you have to dramatise your concept. When I was working on Pasteur, it struck me to realise that this was also the drive of a great scientist eager to introduce a great discovery to the public. When I used the expression “theatre of proof ” it triggered something in Frédérique as she, coming from theatre, was interested in a similar question.

TO: There is a very interesting critique of Brecht’s history plays by Botho Strauß. He says they stem from the pre-cybernetic era and reflect a mechanical understanding of the world: they are about cause and effect and linear processes. Strauß said in the early 90s that our contemporary worldview is shaped by phenomena and concepts like feedback, emergence and chaos theory. Today, this is reflected in our embeddedness in various networks and systems which connect us to figures who are not necessarily human — like other species, landscapes, things and technologies. Strauß also turns away from the Brecht school of dialectic aestheticism for ideological reasons: they are too violent and scientifically too linear for him.

BL: We were interested in the question: what’s linear about linearity? Because it was precisely this which contrasted with the circular feedback thinking of Lovelock: it was more dramatic. We were never sure how to reinterpret the last scene, in which Galileo doesn’t know whether he should or should not apologise for the crimes committed by his “linear view”. Hey says: “If the scientists, brought to heel by self-interested rulers, limit themselves to piling up knowledge for knowledge’s sake, then science can be crippled and your new machines will lead to nothing but new impositions. You may in due course discover all that there is to discover, and your progress will nonetheless be nothing but a progress away from mankind. […] Had I stood firm the scientists could have developed something like the doctors’ Hippocratic oath, a vow to use their knowledge exclusively for mankind’s benefit!”[2] Although Lovelock worked for the British government, that doesn’t mean you can automatically establish a parallel between him and Galileo. Initially, it was my very naive approach to take every Brecht scene and alter them by only using the sentences that could also apply to Lovelock. So, I ended up with a long description of the play (laughs) in which a carnival takes place — which can be easily reinterpreted, just like the episode with the Little Monk. In Brecht’s play, the Little Monk apologises for having abandoned science because he didn’t want to make his parents despair. And, of course, there’s the scene in which the demonstration with the telescope is negated by the royal astronomers and philosophers in light of a series of fake arguments…

We no longer know what kind of planet we live on or how to describe it. It is no longer the singular, stable earth we thought we knew

TO: They cleverly refuse to look through the telescope.

BL: We have exactly the same scene with Lovelock, when several disciplines deny the proof of regeneration by which the planet is capable of regulating itself and by which it keeps life on earth alive. This one-to-one adaptation, however, ended up in a play that was as traditional as Brecht, and we didn’t want to do that.

FA: It was a rehearsal: we used it as a template to highlight the differences between Galileo and Lovelock. It’s important that Brecht makes the link between the cosmological and the political argument. That was one of the main reasons for this parallel, and it is what we ultimately kept in our production “Moving Earths”.

BL: Interestingly, there is Brecht’s play and there is Losey’s version, the film from 1975. You said it’s traditional — I love it! I’ve seen it ten times. It’s very beautiful. Then there is this imitation of Brecht in the first version that we made, trying to follow the same pattern. But in this imitation, there is something completely new: a scientific lecture. As Frédérique just said, in our final version we kept one of Brecht’s central elements: his extraordinary ability to link the social order and scientific cosmology: “And this new art of doubt has enchanted the public. […] They snatched the telescopes out of our hands and had them trained on their tormentors: prince, official, public moralist.” And that’s exactly where I am now. I would say that our experiment, although it’s formally different, is even more Brechtian than Brecht himself. We took the feverish attempt of Brecht’s play to establish a connection between social or political order and scientific cosmology and made it much more intense. When we presented this work to historians of Galileo, they were amazed by the quality of the play. We are both historians of science, so it was very important to us that the historic link was correct. And now, of course, we are trying to do the same with Margulis and Lovelock. So, it’s a different form, because new ways of thinking about the world require new ways of depicting that very world — but we kept one aspect of the Brecht “doctrine”.

TO: Life of Galileo is not a very Brechtian play in terms of Brecht’s own theory. The formal design is rather naturalistic and could almost be Gerhart Hauptmann’s work.

BL: It’s a very un-Brechtian play, we spoke a lot about that.

TO: There is one moment when Sagredo and Galileo work all night. Brecht writes in the set description: They sit down to work eagerly. The stage goes dark but Jupiter and its accompanying moons can still be seen on the cyclorama. When the light returns, they are still sitting there, wearing winter coats. These two lines are stage directions that suddenly reveal the machinery of theatre itself — the “naturalness” of the scene is shown as something artificial by the demonstrative fast forward. Brecht briefly plays with time, only to return to the familiar mode afterwards, which is only possible by this convention of theatre as its basis. This little moment is epic — here, something is done with the scene rather than within the scene. The epic style of Brecht’s theatre is much more pronounced in his earlier plays than in this monumental work. Those plays have a narrator who describes and directs the scene on behalf of the hidden author. But this is not what Brecht does in Galileo. He wrote it like a Hollywood movie: well-made.

BL: Do you know why he used this type of theatre, which is so different from the rest, for this topic?

TO: I think it’s because he wanted to convince as many people as possible. He wrote the play in 1939 while exiled in Denmark. With plays like Life of Galileo or Mother Courage and Her Children he wanted to change the practice of theatre less formally than argumentatively and intentionally. Why do you write a play about a scientist in 1939? The play says: “I believe that people are reasonable. If they have proof then they will change their behaviour. Adverse circumstances do not last forever. Even if they do screw us up.” Which is why Brecht presents this lonely scholar as sensual, devious, an egomaniac — a scientist and practical engineer, capable of malcircumstances and one’s own strength of character. Brecht’s Galileo has political opponents, but in scientific matters he is simply right — and that is a bit boring because we all know that today.

BL: That’s a great difficulty that we face when drawing a parallel with Lovelock. Because no one knows who he is, and nobody believes that he is right. When you draw a parallel, you use a very interesting kind of tension. We spoke to younger people and many don’t know about the scientific revolution that is happening today. They don’t know about the “critical zone” in which water, soil, sub-soil and the habitat of living beings interact and which is so important, because this thin surface layer combines life, human actions and their resources. We made the Brecht play more Brechtian several times, for example in the scene with the Old Cardinal who calls Galileo an enemy of the people: “I am informed that Mr. Galilei transfers mankind from the center of the universe to somewhere on the outskirts. Mr. Galilei is therefore an enemy of mankind and must be dealt with as such.” When you parallel this moment with Lovelock, people tend to associate with the logic of the Cardinal — not with the scientist. Because who is this man who has come to destroy the cosmic and social order? It’s really extraordinary to see what happens when you don’t take a scientist who is well-known and everyone agrees with, but a scientist who, like Lovelock, is controversial. The play shifts in very interesting ways. At the Pompidou Centre, people would say: “Ah, wow, the Cardinal is actually right.” Why is that? Because the Cardinal points out most convincingly what the scientist is destroying, namely the social and cosmic order. It is easy to identify with the Old Cardinal when Brecht has him say: “I tread the earth, and the earth is firm beneath my feet, and there is no motion to the earth, and the earth is the center of all things, and I am the center of the earth, and the eye of the creator is upon me.” Our current situation poses the exact opposite. Though we may be experiencing another cosmological change, the same kind of shift between science and social order, this time we don’t know where we stand. Do we support the lobbyists? Do we support the climate sceptics? Do we support science? We no longer know what kind of planet we live on or how to describe it. It is no longer the singular, stable earth we thought we knew. Instead, a multitude of planets lie in wait for us to explore in order to discover which one we should land on. In light of this confusion, Brecht’s play suddenly appears to be an extraordinarily profound and contradictory mix.

Landing on earth, being “down to earth” requires rethinking what Gaia is. She is not an object in the old tradition of Galileo, but an interconnected and overlapping network of actors

TO: How would you describe Gaia as a character?

BL: Scientifically speaking, we now have a much better idea of what Gaia is — a non-character, so to speak, something that is vastly different from nature. The distinction between nature and Gaia is very clearly defined, because when people talk about nature, they include everything from the Big Bang to COVID-19. COVID-19 is in Gaia, the Big Bang isn’t. There is a scientific definition of Gaia. Then there are many myths about Gaia in the writings of the ancient Greeks and the multiplicity of names for Gaia in Greek tradition. She keeps changing names. She is not a character who is easy to situate. Then there are other interesting works on what Gaia legally is, what sort of legal status she represents. This question weighs on us. Gaia has some sort of authority, but she is not the state. Then there are a lot of concepts of understanding Gaia in terms of origin. That is the eco-feminist tradition, represented by Donna Haraway and Isabelle Stengers. There is a vast number of people who are trying to rethink what Gaia is, because that’s where we are right now — but we don’t know where we are. Landing on earth, being “down to earth” requires rethinking what Gaia is. She is not an object in the old tradition of Galileo, but an interconnected and overlapping network of actors. We are all trying to feel our way there, because all the attitudes, feelings, and the resistance of the material are different, depending on whether you land on the Galilean earth or on the Lovelockian-Margulisian earth.

There is a very interesting reinterpretation of one of the last scenes of Brecht’s Life of Galileo — the one with Andrea, which is very weird and was rewritten by Brecht after the Hiroshima bombing. It’s a very complex reinterpretation of science’s mission: the purpose of science should solely be to ease humankind’s burdens. In that sense we are concerned with the same situation, where we reinterpret things, not only because of the atomic bomb — which is still there, by the way — but because of the ecological change which we all need to re-evaluate. If you are “down to earth”, you explore a general ontology, which is as different from Galileo’s as Galileo’s was from the scholastic version he was attacking — and profiting from, actually. We should not hurry to determine what Gaia is. And we now need what Frédérique is pointing out to us, which is to capture a whole set of different dispositives, including your and Tino Sehgal’s project “Down to Earth”. The “Critical Zones” exhibition in Karlsruhe is also very important to me as it presents all the different versions of Gaia.

FA: Gaia is not a kind character. I think the detour via the mythical Gaia is very important because in mythology Gaia is terrible. Someone — I think it was Margulis or Stengers — said: “Gaia is a bitch.”

BL: That was Margulis and she said: “Gaia is a tough bitch.”

FA: I was very struck when Bruno wrote this little article about theatre and science more than ten years ago. The last line of this article, which is written as a dialogue between fictional characters, is: “Gaia enters the stage”. At that time, I didn’t understand what Bruno meant, because Gaia was not a name that appeared in that text. But of course, Gaia was entering the scientific stage, the political stage and the theatrical stage, all at the same time. One aspect we intensively worked on during the “Gaia Global Circus” project ten years ago was the stage design. For us, Gaia, who we portrayed as a flying canopy, became one of the players on stage, the fifth actor. It was a very naive model, and that’s what we loved about it. It was a naive model of feedback loops. One of the questions for many climate scientists at that time was how to design climate change models that are not only more and more accurate but also increasingly convincing. My own theatrical answer was this floating stage device, a theatrical model, which was of course a very simplified representation of Gaia. But some aspects of Gaia were kept: the feedback loops and the self-animation.

TO: In my understanding, Gaia tries to keep everything alive. A mother can also be a “tough bitch”.

BL: She is a good female mother. She is not a bad mother.

TO: That makes me think of Lyotard’s idea that male and female are not biological categories, but different relations to death. Masculinity, in the metaphysical sense, puts the idea above life. It sacrifices itself and others for an abstract principle. Femininity, in the metaphysical sense, is that which does not sacrifice life for an idea. I can’t imagine Gaia as a character destroying life.

BL: But she did many times. It was often a close call.

TO: The volcanoes and the comets.

BL: Or the ice. It was a really close call. There is nothing balanced in the Lovelockian and Margulisian Gaia. She is not balanced; she is just the accumulation of a succession of careful, lucky moments, so to speak. I don’t think we should draw any conclusion from that. This is why I’m worried about labelling her a female character. It’s a mythical character, it goes deeper than the difference between male and female. It’s an original character. It’s about origin, yes, but not about her being a female character. In the history of the mythological as well as the scientific Gaia, there is a “tough” way of explaining how life continues. There is nothing balanced about it. That’s a very important aspect. It’s not nature in the sense of a positivist or neo-Darwinian struggle for life. It has nothing to do with balance and union. Margulis even more than Lovelock was quite insistent on the non-motherly character of Gaia. That is something that has to be worked out with great precision. It’s a vastly more interesting character if it’s not restoring balance, particularly not on a global scale. It has a very strange way of being global, as we saw with COVID-19 spreading everywhere from one person to another. For me, the virus is a very beautiful example of the sort of thing that allowed Gaia to grow. It has nothing to do with being big: it’s very small. A small entity, accumulated over four million years, producing big effects. It has none of the characteristics associated with Mother Earth. So, why do you call your project “Down to Earth”?

TO: In these times of transition, it is about examining the question: what can we hold on to that will help us find stability? That’s why we like the double meaning of your English book title: being “down to earth” is something pleasant, you know where you stand and you are relaxed. But it also draws our attention to something very concrete, namely the realm of this earth in which we interact and which you call the “critical zone”. This thin cloak of physical life, spanning from the depths of groundwater wells to the peaks of vegetation. You also talk about helpful, underestimated practices such as tinkering, the work of negotiation, efforts to create overlaps between different national and local interests and structures. In our eyes, this has a lot to do with certain artistic practices of our time.

We are immersed in Gaia, but we have to find a Brechtian, non-immersive way to show people that they are immersed

Many of them are activist. And many of those activities do not look like art at all. Experimental sustainability measures are often a lot more advanced than what is happening in the field of art. So, we have everything from experimental modes of agriculture and nutrition to new kinds of housing all the way to artists who bring living earth into our exhibition space. Or a sawn-up Porsche. Or shamans. The whole concept of the exhibition is also closely connected with the work of Tino Sehgal. We will forgo air travel and the use of electricity while attempting to bring various target audiences together in this exhibition. This allows us to interrupt our typical business operations and routines in the art sector — a disruption which, at the same time, offers us concrete possibilities. You will feel that something is different once you are there. For example, that it gets dark when the sun goes down. That’s why your book Down to Earth is so helpful to us, your idea of the third attractor: it’s not the local, it’s not the global, it’s the whole of life’s “critical zone” — a very concrete territory which connects us to everything else.

BL: I’m interested in the German title, which translates to “The Terrestrial Manifesto”, because “terrestrial” doesn’t really work in German. You would not use the term terrestrisch for a festival.

TO: No, it’s not really a popular term. Just as how we no longer refer to it as “terrestrial radio”. But the title The Terrestrial Manifesto appealed to me anyway. Because who is speaking? Earth? Just before collapsing? For us, the climate is the most prominent example of an immersive phenomenon, of something that we are not only confronted with, but embedded in — and through which we are connected with all other human and non-human actors. For us, it’s the climax of a long development of our programme series that pushes the limits of the term “immersion”. From art to social transformations — like German reunification — to the climate: they all represent processes which can no longer be described in dualistic terms. The last exhibition Tino Sehgal and I did together was called “Welt ohne Außen” [“World without an Exterior”].

BL: With our lecture “Inside” we want to demonstrate that there is no outside, no exterior, but only the thin and fragile skin of the “critical zone”. We want to demonstrate that we don’t walk on the earth anymore, but with it. And in “Moving Earths”, we describe a reciprocal parallel with Galileo, who is looking at the moon and imagining that he can watch the whole cosmos with this “view from nowhere”, whereas Lovelock is giving proof of sulphurous compounds in our environment with his electron detector. Thus, Galileo is interested in the vast outer realm while Lovelock is focused on the “critical zone”.

TO: The subject of language is also very important in Brecht’s Life of Galileo. Galileo always asks the scholars and people of status to speak colloquially in front of his companions, rather than in Latin. This is what we associate today with the term “plain language” in museum publications or in offices. I have noticed that a term like “immersion” has produced a great deal of rejection in the German-speaking world. It was very quickly associated with fear, maybe because the Germans had a painful experience with the affective and intuitive in the Third Reich. When we use this word, it is usually on a different level of meaning — for us, it marks the end of a worldview based on the isolation of discrete phenomena, on a dialectical back and forth. For us, “immersion” means living in systems that are characterised by hybrids and quasi-objects, by actors who can also be machines or other species with whom we are connected in many different ways — all the entities you both described earlier in connection with Gaia.

BL: We are immersed in Gaia, but we have to find a Brechtian, non-immersive way to show people that they are immersed. This is what we had in mind with “Inside”. Although our theatrical means were very artificial, there was not a single moment when you could believe the situation — that is the Brechtian part. But it’s also about being inside.

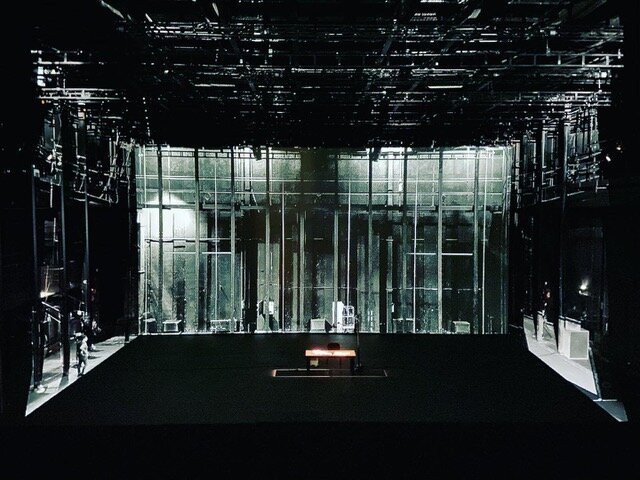

TO: Exactly, that’s what it’s about. Immersion makes the proscenium arch invisible. Brecht, on the other hand, made it visible. Not in Life of Galileo, but in other plays. “Don’t stare so romantically!” — it’s just theatre, treat it like theatre. But you can also use immersive processes that make the proscenium — as a sign of the artificial— vanish in order to illustrate that “the normal” is a state always signified by quotation marks. Because this enables us to realise that we have somehow “slid” into something or that our sense of reality is dissolving. For the fish, there is no water — not until you briefly take it out of the water, that is. VR-based works can show this quite impressively. When I move as an avatar in a VR world, I can feel a real sense of fear standing in front of a virtual abyss. My head knows I’m in a game, but I’m experiencing the fear for real. In the theatre, nobody ever really loses awareness of the artificiality of the situation. At the same time, it is an experience that enables us to feel something that goes deeper than mere reflection. Through certain gestures, Brecht’s theatre is able to make the mode of representation itself visible — and nevertheless enchant us. Usually, I see the bird outside the window, but not the window itself, as Thomas Metzinger says. Theatre can create an awareness of this. When we talk about art, the use of the term “immersion” gets a little more complicated, because we have to distinguish between the psychological experience of the eradication of borders between ourselves and others, which is usually called “empathy”, and the more technical experience associated with a specific genre or type of performance in theatre, digital media and concerts. The latter is characterised by the fact that I actually physically sit in the middle of the stage — the scene surrounds me and does not face me as an “object”.

BL: Frédérique thinks I have a very naive way of creating stage characters, and says: “This is finished, we are riding a post-romantic wave.” Because you risk immersing the audience in a thing; the thing about the fourth wall, which has to be destroyed…

FA: That’s not exactly what I said! And it’s not an absolute doctrine. I just think that we all have to acknowledge the limits of a specific linear dramatic narrative. I believe that theatre people and writers need other ways of telling stories, because the actors on stage are not exclusively human anymore. Bruno leads us writers and directors towards a new path, but at the same time, Bruno, you always say: “I like the old theatre, with characters and a story”. What do you have to say to Bruno about this, Thomas?

We want to demonstrate that we don’t walk on the earth anymore, but with it

TO: In the movies, I like old-fashioned too, I’m afraid. But in theatre, I like the oscillation I mentioned earlier. And in theatre, to my mind, we need a more modern form. One which shows the window, so to speak, and not just the bird. Frédérique, you have just described that you want to show different kinds of protagonists — not only people, but also things, the apparatus of theatre itself. This is one of the most interesting developments in recent theatre. When we consider “immersion” as a genre of its own, we encounter the phenomenon of “world-building”, like in science fiction or game design. The works of SIGNA or Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller create spaces that are “world capsules” — cosmoses which you can enter. And everything there is scripted. Just like in the real world “out there”, which consists of very controlled environments. With this kind of “world-building”, clever artists can lead us very, very far into other areas of understanding the world and ourselves. When we talk about immersion on stage, we are talking about real time and real feedback, which is ethically very challenging.

BL: In your argumentation, how would you characterise a lecture? Frédérique’s idea is to use a lecture to remove the fourth wall by addressing the audience — in real time, of course, and improvised. How would you view a lecture if it were fiction, as Frédérique proposes? Or what about one that is not so fictional? Because I give real lectures!

FA: In a theatrical setting, people are used to lectures being fictional and the fact that we mock or play with this academic format. At the same time, our performance-lectures are actually real lectures which share a thought in the making. Tino Sehgal has another way of doing immersion, which was very important to me when I discovered it in Kassel at documenta 13. And I have never forgotten this moment of discovering Tino’s way of creating situations. Even when I stage lectures, which are a very front-on kind of format, I try to create this moment of encounter.

BL: Is this a new genre of theatre, Thomas?

TO: If you extend the concept of theatre very far, which I think is good, then: yes. Maybe a lecturer should be considered more of a performer in the contemporary dance sense than an actor. Because you are not performing a role, you yourself are the material of that role. The format of the staged lecture brings philosophical wonder to the theatre, and in order to do this you need to use all the techniques of showing and telling that the complex apparatus of the stage requires. Compared to the works of Tino Sehgal, I would say that he doesn’t need a proscenium anymore. He uses exhibition halls because he is creating new forms of ritual. A ritual is always a kind of immersive encounter; it’s not something you look at from the outside, but a “social room” which you enter. Tino creates absorbing spaces with his choreographic work. Tino’s work is no longer about the unfolding of conflicts and narratives: it’s about meandering experiences within a specific situation. The reality of the situation is more important than the concept of development, which was essential for Brecht’s plays. But coming back to your question — yes, I think this is a new genre of theatre, exactly like the new form of exhibition that we have established here. Perhaps that is why our work fits together so well.

References

[1] Bruno Latour: Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Trans. Catherine Porter, Polity Press, 2018.

[2] Quotes throughout this interview were taken from two translations of Brecht’s Leben des Galilei. Bertolt Brecht: Galileo, Trans. Charles Laughton, 1952 and Bertolt Brecht: Life of Galileo, Trans. John Willet, Bloomsbury, 1980.