Lethe Runs over the Screen. Sid Iandovka and Anya Tsyrlina at Rialto6, Lisbon

In a chapter of his final book Cruor, Jean-Luc Nancy comments on a note—also the last we have on record—by Freud: “Mysticism: the dim self-perception of the realm outside the ego, the id.” This dim perception conveys a peculiar knowledge whose enigmatic character emerges precisely because, due to an apprehension of itself, it remains equally dim. “Mysticism”—the dim perception—emerges not through a symbolic expression or the allegorical unfolding of a hidden meaning, but through what Schelling called “tautegory”: the self-expression and immanence of a medial milieu whose art obscures itself to its own perceptibility.

Over the past decades, Sid Iandovka and Anya Tsyrlina have developed a body of work that draws on the afterlife of experimental film, anachronic montage from Soviet film archives, and the last vestiges of the nearly forgotten underground scene in Novosibirsk around 1993-94. After the recent screenings of their films at various festivals, the exhibition at Rialto6 consolidates the interwovenness of these works and for the first time reveals their complex spatial coherence.

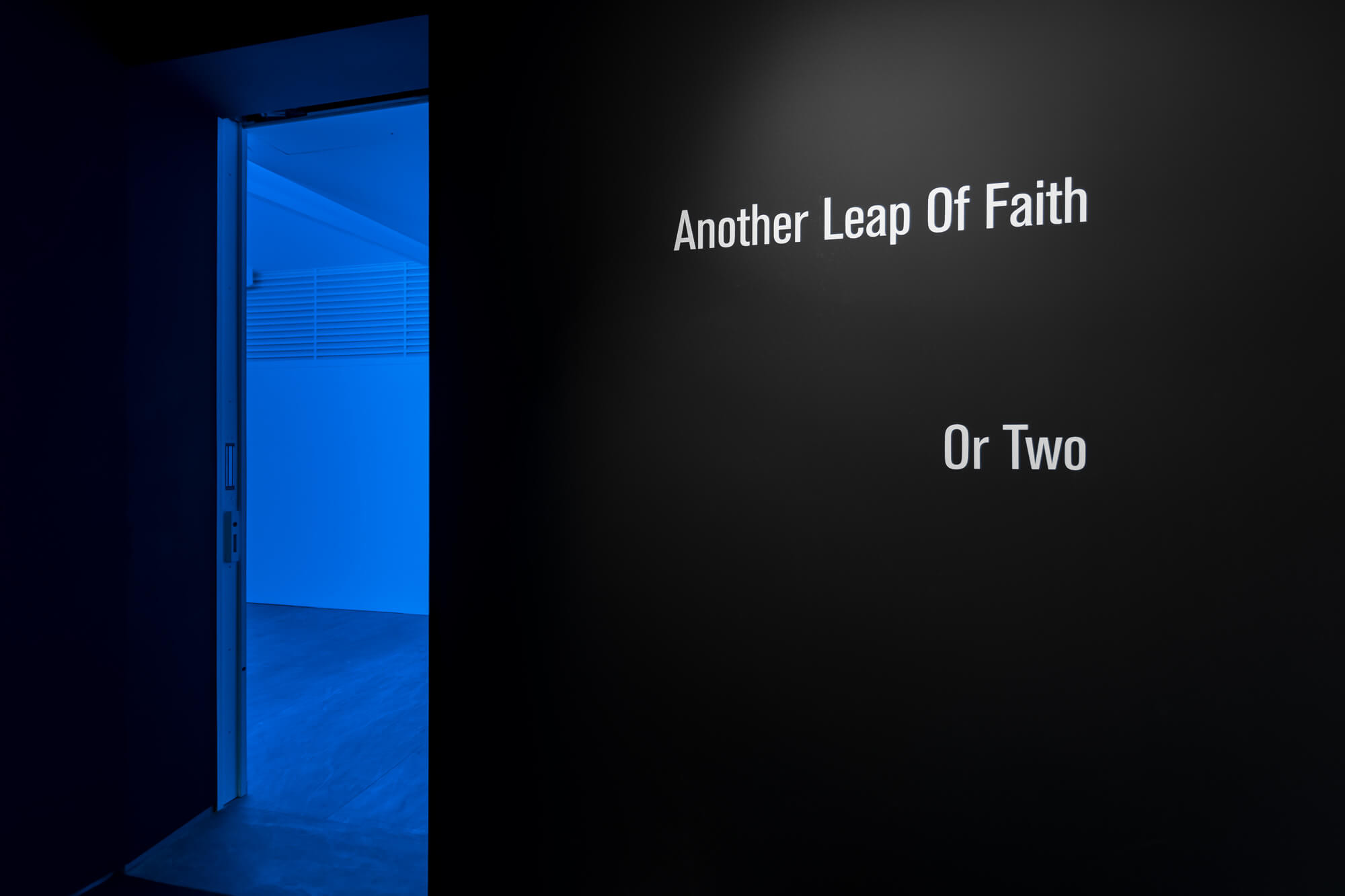

Contrary to institutional conventions, the only text that appears on the wall at the entrance of the exhibition is its title. Further information and two accompanying texts are provided in the folding brochure for the exhibition, which shows a collage of stills from all the films on its front, as well as an arresting drawing of a figure struck by an arrow that belongs latently to the iconography of putti or Cupid figures, but here is itself the target of the very arrow that, according to tradition, it should be in a position to shoot. The arrangement of the works in the space is handled analogously to the collaging of the films together with this drawing on the cover sheet. The films in the exhibition do not remain separate in themselves.

What is immediately felt as a distinct cinematic style is not altered for the exhibition, but rather conceived with logical, pragmatic consequence as a space in which the concentration on the individual elements becomes equally apparent as an overall ambient impression. The formal properties of the films—such as the constant perforations, temporal manipulation within the images or obfuscation of the filmic surfaces through filters, distortion, oversaturation, or light sources, as well as the exploratory departure from landscape motifs—engender a phantasmatic pleasure in the penetration of the images and open the exhibition up as one larger unit of sound-display-montage. The floor and the black-painted walls of the exhibit are used equally as screens. On the other hand, a painted screen remains empty so it can be illuminated. The internal time of the works unites with this generous spatial openness, accompanied by a soundtrack that consists of a compilation of all the film tracks and combines cosmic, spherical sounds with a cyclically repeated counting pattern. Within this montage, various cultural realms, such as music, cinema or video, become an autonomous space the meaning of which is condensed to the point of indecipherability, for example when from a dim interior with a view of a Novosibirsk traffic circle still pulsating in the harsh, cold winter light, the Miami Vice theme composed by Czech jazz keyboardist Jan Hammer resounds as a cipher of a lost kernel of time in the USSR of the early 1990s.

The exhibition superimposes different formats, time sequences, and layers of experience over one another, generates a topology of vertical and horizontal structures, and plays with grave and strident figures and different tempos, as well as stages of abstraction and figuration, which over time create a dynamic but startlingly consistent space of the moving image. Conspicuous throughout nearly all the films are the slow-motion sequences and the backward orientation of the camera toward the rear spaces, flashbacks, veiled gazes, or repoussoir figures turned away from us, which in turn appear anonymously on the horizon or in the depths of a varied but atmospherically recurring hinterland. The latter’s untimely—in the best sense of the word—present of legibility is equally evident and impressive as it resists comparison or classification through categories of contemporary art and experimental film.

In addition to the topological figures and figural abstraction, there is also a transversal force that allows the films to flow and penetrate into one another. Like a wafting veil, the dim perception of a forgetting of the projected moving image and the lived time within it settles over the spatialized display of the films. In its displacement into the space of art, which can be experienced as spatial, sculptural, figural, and sonic, this veil remains perceptible as an image of forgetting. In other words, we enter a dream that is about another dream, which for its part has begun to end for the dreamer, is already lost, or whose meaning escapes us. Like the cinematographic equivalent of a word on the tip of one’s tongue, the sense of this dim perception remains perpetually mute and untranslatable, pre-linguistic and pre-conceptual, remains image and figure in the process of forgetting, like the rising, ancestral and auratized figure of an angel without the angel in Meteor—because the image reminds us of this without actually being able to do so yet for lack of attributes.

In this sense, across the screens of Iandovka and Tsyrlina’s films flows the river of forgetting and obscuring (“oblivion” combines both). Since ancient times, Mnemosyne, the river and the goddess of memory, has been the guardian and unifying force of a cultural memory of images, their flourishing, safeguarding and preservation. The other river from the underworld, Lethe, in contrast, ensured the forgetting of images. In the work of Iandovka and Tsyrlina, the retreat of the cinematographic image leaves behind new modes of the pictorial: where Mnemosyne dies because its flow must dry up in the desert, there can still emerge the pictorial space of hallucinations and phantasms, like the Fata Morgana on the horizon of the most abstract desert landscape. The loss of the image thus itself has a genuine pictoriality. It produces the image of its absenting. Forgetting itself congeals into the image of forgetting. The disappearance and exhaustion of the source of memory leave behind the dim perception, the trace of a withdrawal of meaning.

At one point in Godard’s Histoire (s) du cinéma, Serge Daney says—in Paris in the mid-1980s, so while Iandovka and Tsyrlina were still living in Novosibirsk—that cinema at one time, but then only ‘once long ago,’ had had a chance that it did not know how to use and now has to learn to understand its own past from this lost utopia, from a history that could have gone differently. Iandovka and Tsyrlina produce their work to a certain extent in the posthistoire of this labor of mourning and remembering, because remembering as a deconstructive montage is no longer entrusted with the construction of a past as a present, but rather the forgetting of images, the loss of images, replaces this visualization, because Lethe flows continuously and with increasing surge across the screen and through the archive, and these are now the images we have to read. They convince and interest us more, perhaps since long ago.

In a reverse shot of the projection light, the light in the dust, we dimly still perceive the old cinema audience and the cinematographic dispositif. Alone, the images disappear, the shooting of the light images takes place without meaning, emptied and mechanically reduced to the mere shooting of the film, a bit like the idea of the ‘flashes of light’ in Markopoulos’ Eniaios, only no longer even on a blank screen.

Toni Hildebrandt and Katharina Hölzl

Photos by Vasco Stocker de Vilhena