Dream Together: a Conversation with Members of the Panta Rhei Collaborative

The research for the third edition of Tbilisi Architecture Biennial TAB 2022 focused on the concept of temporality in urban and social life. Taking as an example the recent history of Georgia, the notion of temporality was considered through three main categories: time, space, and the built environment. The aim was to discuss architecture in the context of each of these categories and to reflect on how architecture coexists with everyday life, not solely in regard to its physical dimensions, but in terms of duration.

Tinatin Gurgenidze, one of the co-founders of TBAT, spoke with three members of Panta Rhei Collaborative, Bene, Eugenio, and Jan, about their founding, their project for the Biennial, and the potential futures of AI in urban planning.

The series of materials on architecture, infrastructure, and the landscapes of Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia was made possible thanks to the support of the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia.

Tinatin: Can you tell us how and when the Panta Rhei Collaborative was founded?

Bene: We founded Panta Rhei Collaborative back in 2020 following a period of studying together. Our objective was to establish a platform where we could continue discussions focused on broader ideas relating to architecture and spatial practice, especially relating to theory, research, and education, in addition to architectural practice.

Eugenio: Our objective was to create something that would grow and develop over time. We wanted to create something other than a traditional office structure but more like a constantly expanding network of shared knowledge and resources that facilitates collaborations between different practitioners.

Tinatin: What is the idea behind your work?

Eugenio:. Our desire is to explore new processes and formats for the interrogation of the city, creating support networks to open up about issues such as ethical practice, inclusivity, and the commons, as well as working together and enjoying it at the same time.

Jan: We’re also interested in exploring the possibilities of using tools that are traditionally frowned upon or stigmatized within the architectural profession, such as Artificial Intelligence and machine learning. We want to interrogate this technology and try to explore how we might put aside our biases and begin to understand how it could be put to good use.

Tinatin: How did you hear about the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial Open Call and why did you decide to participate?

Jan: We heard about the TAB Open Call from a group that had participated a year before. The central question of the open call, “What’s next for Tbilisi? , '' was intriguing because right from the start we knew it was one that we, as outsiders, could not answer ourselves. We were motivated to explore what postcolonial, international collaboration can mean and whether we could articulate, in some way, this new role that we agreed professional urbanists/spatial practitioners have to take.

Bene: We also saw it as an opportunity to bring to light the possibilities of using tools like AI and machine learning, which may be seen to pose a 'threat' to our professionality. We wanted to interrogate this technology and explore how we could use it.

Tinatin: How does the title of your Project “Dream Together” respond to the theme of TAB 2022 and do you propose a dream future that many see as so uncertain in Georgia and in the region?

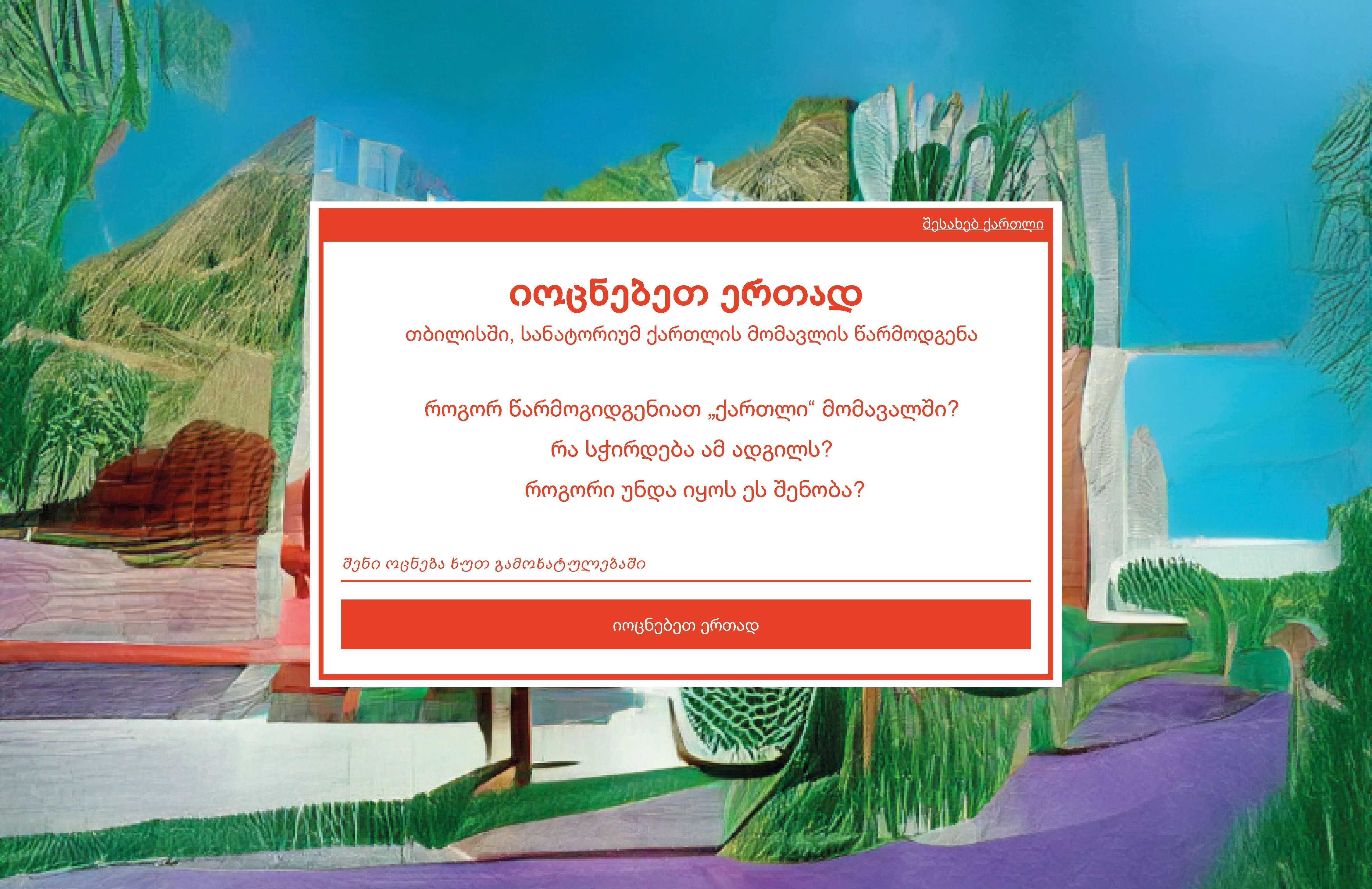

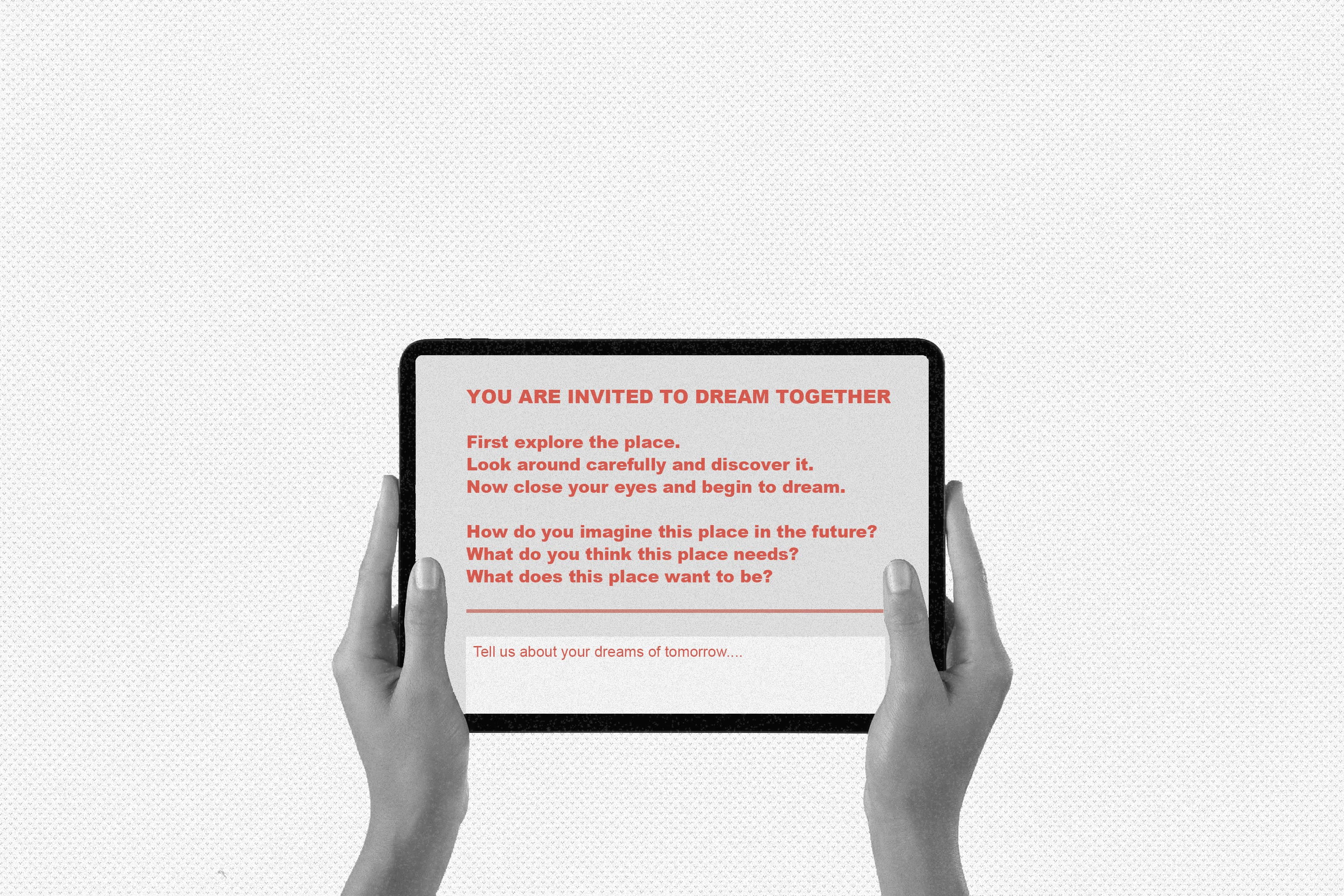

Bene: We wanted to bring two things to the fore with the term “dream.” On the one hand, a dream is a unique form of consciousness while the body is mainly at rest. We wanted the people living in Kartli Sanatorium to experience a moment of consciousness while allowing them to see things from a different perspective than that of their everyday life. On the other hand, the term dream expresses “wishes for the future.” We wanted the local people to be able to express their wishes together so that they are heard and included during the biennial.

To really answer the question “What’s Next?” in the future, everyone should be allowed to dream first.

The biennial theme is linked to the dream worlds in which we have tried to facilitate a participatory process to understand, from the residents themselves, what could come next.

Tinatin: What is the project “Dream Together” about and how is it connected to the residents who had to leave their homes in Abkhazia in the 1990s and have been living in these conditions for 30 years?

Jan: The basis for the “Dream Together” project was another work I had done with Julian Volken and Linus Arnold, where we extensively researched how Generative Networks (NN, GAN), basically text to image AI, can be used as a tool to visualize and express the sentiment of a large number of people.

Central to this idea lies the assumption that the language of future visions and projections in fields such as urbanism, Spatial-planning, etc., is very visual; it requires skill and access to the means of creating images to support ideas, dreams, and wishes.

Eugenio: As Jan mentioned, we found ourselves as privileged Western Europeans in a new context. We found it almost impossible to propose and/or dictate a future for a community and context we are quite removed from.

Learning about the abysmal conditions that the internally displaced people had to endure living in the Kartli Sanatorium made us question the current engagement processes used by urbanists, planners, and politicians to provide housing that offers minimum living standards for less fortunate communities.

For this, we wanted to explore a more relatable visual medium almost totally removed from reality in order to question common planning and regeneration practices. We knew that the images that would be generated would not offer tangible and credible buildings. Still, our intention was more to break from these traditional methods and to provide local people with an opportunity to have a say, however left field and non architectural their ideas might be.

Tinatin: How did you imagine visitors and residents participating in the “Dream Together” project?

Jan: The ideal scenario, of course, would have been to meet with the residents to introduce the idea and gather answers with the help of local mediators and translators. The actual location and localities of “Dream Together” required such a sensitive approach that was impossible remotely, so we had to accept that the project would stay in a specific prototypical state.

Tinatin: In your opinion, what is the output of the “Dream Together” project?

Jan: In terms of their output, there are two dimensions. On the one hand, we now have a list of wishes / or dreams from the residents that would not have been collected without the project “Dream Together,” especially without the biennial last year. With these inputs, we can work on possible outputs.

On the other hand, we were also interested in the tool itself.

We wanted to test new possibilities of participatory processes. Here, the goal was to have a conversation about the idea of this tool rather than the actual output itself.

Tinatin: How will the video installation at the Kartli Sanatorium change over time?

Bene: Initially, we imagined it to change in real-time as inputs were being added; however, this posed several issues from a processing perspective. In an ideal world, this could have been permanently set up as a virtual platform even after the end of the Biennial, but this was impossible.

Realistically, we could imagine that a series of these visual installations might be produced at several points along the road of the Kartli sanatorium, maybe even adopting different visual prompts of the place.

In essence, the end product was imagined as a testing vessel for the tool to be used in different instances around the city, with similar structures facing an ultimatum on their lifespan.

We would also like to develop and refine the tool to give more specific visual outputs. We found that the technology had begun to reference itself after many iterations of the video. Traces of the Kartli had almost faded completely, but this could also be part of the beauty of the images produced. This disassociation is more of what is needed in order to consider more radical futures for the place.

Tinatin: What are the potential benefits of involving residents and visitors in the urban development process through digital technologies in general?

Eugenio: One benefit of this digital technology is its open-source nature and the fact that it is available to anybody with an internet connection, which, these days, is the case even before basic needs like labour or accommodation.

Before, people might have struggled to access formalized processes of participation and engagement in social life; the internet has facilitated and democratized these processes — I am thinking of live translation engines, online voting and petitions, and AI helping people with disabilities or communication impairment.

Essentially improving accessibility for all, especially in an increasingly globalized world where you have a diverse mix of cultures and communities inhabiting places and spaces, can be challenging, especially when adapting to new governance and planning systems.

In the UK, for example, it is still quite difficult to have a say in the planning system as a citizen; although you can speak out about planning applications, finding the proper channels to do so is often tricky. We should be working towards inserting residents and everyday people into that cycle of engagement.

Tinatin: How might artificial intelligence continue to impact urban development in the future?

Jan: This is a question I don’t feel qualified to answer, partly due to the uncertainty or absence of dominant movements I believe in observing within urban development. I see one of the most significant shortcomings of the contemporary city is the lack of stories it is telling or at least the diversity thereof. One of the more tangible impacts of ChatGPT and Midjourney we observe today is that they enable expression. Any production of stories that are enjoyable to consume required craft and was therefore inherently time-consuming, a luxury if you will. Now, this does not mean that suddenly everybody will tell incredible stories, but certain obstacles, maybe even inequalities, will start to disappear.

Tinatin: What are your dreams?

Eugenio: That question always catches me off guard, as it makes me question my journey and where it has brought me. I have several individual dreams that involve being able to dedicate more time to my creative side projects, music, performance and artistic practices, and finding the optimal working context to balance them all out while also making enough money to survive and maintain these projects.

But I think one dream that I believe I share with the rest of the group — and it is more of an aspiration than a dream — is that, in whatever projects we realize or put together, we are constantly creating connections between people and places that might never have met otherwise.

In doing so, we want to create situations where there can be conversations about interests, beliefs, morals, positions, politics, society, and culture, but in a totally non-confrontational manner and in an informal and friendly way. These are the situations in which I feel most fulfilled, and I would like to carry this forward both personally and with PRC.

Bene: There are, of course, different dreams that one can have. Regarding the Panta Rhei Collaborative, I would like to continue working on such relevant topics, where we try to involve other people with different interests.

We now have an atelier in Zurich where we can work on such topics online and physically.

The desire to work together is often difficult due to the long distances between us in the team. Fortunately, there are increasingly more opportunities in the digital realm that make it easier to stay in touch and work together than there were a few years ago.

My goal is to create a correlation between the two on the one hand, new tools creating new opportunities, but on the other hand, a direct, physical exchange with the people.

Tbilisi Architecture Biennial

The Tbilisi Architecture Biennial was founded in 2017 as a platform unifying local and international professionals. Every two years it organizes exhibitions, installations, workshops, symposiums, and activities around a critical, timely issue of focus that is meant to gather citizens, stakeholders, and field professionals so that they may analyze the issues of architecture and urban planning of Tbilisi and beyond.

Panta Rhei Collaborative

Panta Rhei Collaborative is a group of architects based between London, Berlin, and Zurich that was founded in 2020 following a period of studying together at the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio. They wanted to create a constantly expanding network of shared knowledge and resources to facilitate the collaborations of practitioners. Their “Dream Together” project was one of the proposals chosen from the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial 2022 Open Call in the category of Digital Projects. It focused on residents who had to leave their homes in Abkhazia in the 1990s and have been living in inhumane conditions for more than 30 years. For this project they used Generative Networks (NN, GAN) to visualize and express the sentiment of a large number of people’s dreams and wishes for the future. The project was presented in the form of a video installation during TAB 2022.