Silent Nature in a Boisterous Culture

“The hammers roar, the machines rattle. (…) Countless bells ring incessantly. A thousand doors slam open and shut. (…) Now the telephone rings. Now the horn announces an automobile. Now an electric car rattles past. A train crosses the iron bridge. Across our aching heads, across our best thoughts. (…) Every intellectual and every theoretical creation is invaded by a noisy mob and the ‘practical’ interest of a noisy mob. (…) Every moment a new unpleasant noise!”

Theodor Lessing in Der Lärm: Eine Kampfschrift gegen die Geräusche unseres Lebens (1908)

More than a century has passed since German philosopher, writer and journalist Theodor Lessing published his manifesto against noise and yet it sustains a timeless quality. Growing up Lessing witnessed the shift from an agrarian to an industrialized society first-hand. This led him to the writing of several works on the topic of noise pollution as a direct effect of industrialization and its negative influence on society. Lessing argues that noise pollution is not only detrimental to people’s health but also that it diminishes people’s quality of life and dehumanizes society as a whole.

In accordance with Lessing’s observations and arguments, our object of choice, the sound of a boat’s engine, recorded on a boardwalk next to the Danube in Linz serves as a symbol for the invasiveness of industrialization on human and non-human lives. Not only does it disrupt creative and contemplative thought processes, as described by Lessing, but it also drowns out any other potentially pleasant and more inconspicuous sounds of nature and that way asserts its power over all organic sounds in the area.

In effect, to investigate the implications of noise pollution around riverscapes on human and non-human lives is really to investigate the way humans relate to the natural environment. What ways of being with nature does industrialization foreclose and why is it important to consider the seemingly askew dynamic between culture and nature?

This paper aims to address the aforementioned questions from a sociological perspective, namely from the perspective of contemporary German sociologist Hartmut Rosa’s resonance theory.

Resonance Theory

Hartmut Rosa’s thesis underlying his extensive work Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2019) is “(…) that in life, it depends on the quality of the relationship with the world, that is, on how we, as subjects, experience the world and how we take a position toward the world; on the quality of world appropriation” (Rosa, 2019, p. 19). This assumption represents a counterproposal to the current sociological canon, which measures the quality of life solely based on a person’s resource endowment (Rosa, 2019, p. 22). Rosa poses the following question: “When is life successful, when does it fail if we don’t want to measure it by resources and options?” (Rosa, 2019, p. 20).

According to him, life succeeds when “[w]e have an almost libidinous attachment to it” (Rosa, 2019, p. 24). Only then does something like a “vibrating wire between us and the world” emerge (Rosa, 2019, p. 24). This is what Rosa calls resonance.

Therefore, a successful world relationship is characterized by a resonant connection to the world, while a silent or alienated world relationship represents an unsuccessful world relationship (Rosa, 2019, p. 71). Rosa postulates that “range expansion” and “world domination” lead to alienation, while the search for “reciprocal and creative interactions and the creation of social and extra social connections” leads to resonance experiences (Rosa, 2019, p. 28).

It is exactly this reciprocity between nature and humans that, according to Rosa gets lost in an industrialized society, amongst other things.

Availability of Nature

“The silencing of nature (within us and outside us), its reduction to what is available and still available to be made is, from a resonance-theoretical perspective, the actual cultural ‘environmental problem’ of late modern societies”

Hartmut Rosa (2019, p. 463)

Nature that has fallen silent, due to noize coming from the outside or due to its commodification, can no longer answer as its own agent, and can no longer provide a framework for resonance experiences.

“Resonance (…) is only possible between a subject and a counterpart that can speak with its own voice and thus proves to be a source of strong values. Therefore, people only have resonance experiences where they are convinced that they are touched by something that (for them) is absolutely important, that is, independent of their specific wishes, needs, and desires. Without the concept of such a (resonant) counterpart, people find it difficult, if not impossible, to define themselves and develop an identity” (Rosa, 2019, p. 456).

According to Rosa, it is our way of relating to nature, the very act of trying to make riverscapes available at all costs to fulfill human desires and the din of this commodification, that prevents nature from being the counterpart we would need it to be in order to establish resonance and therefore a sense of identity. After all, it is not for nothing that proverbial statements like Having to listen more closely to nature to find oneself emerged and continue to be used in cultures across the world (Rosa, 2019, p. 456).

Commodification of Resonance

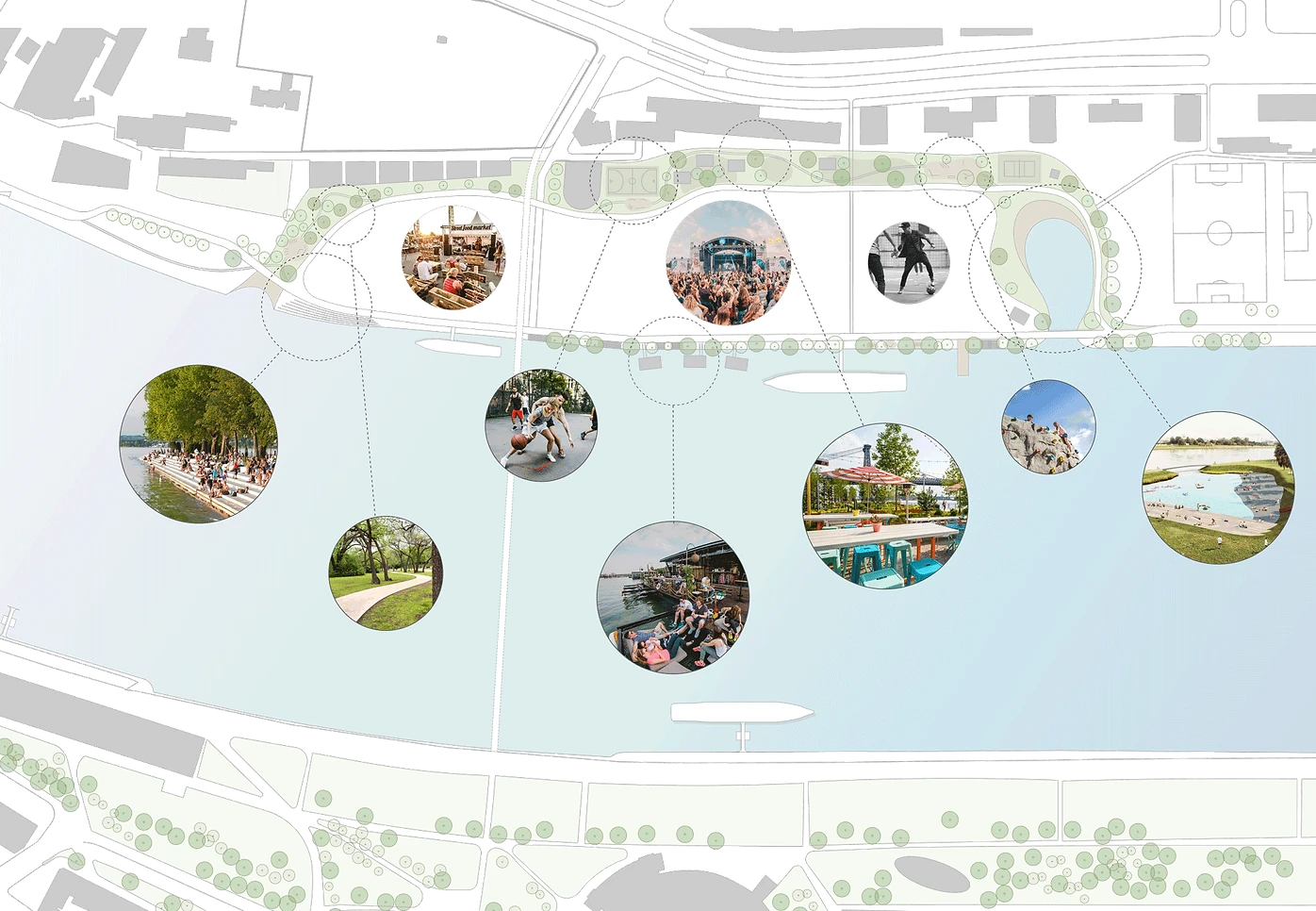

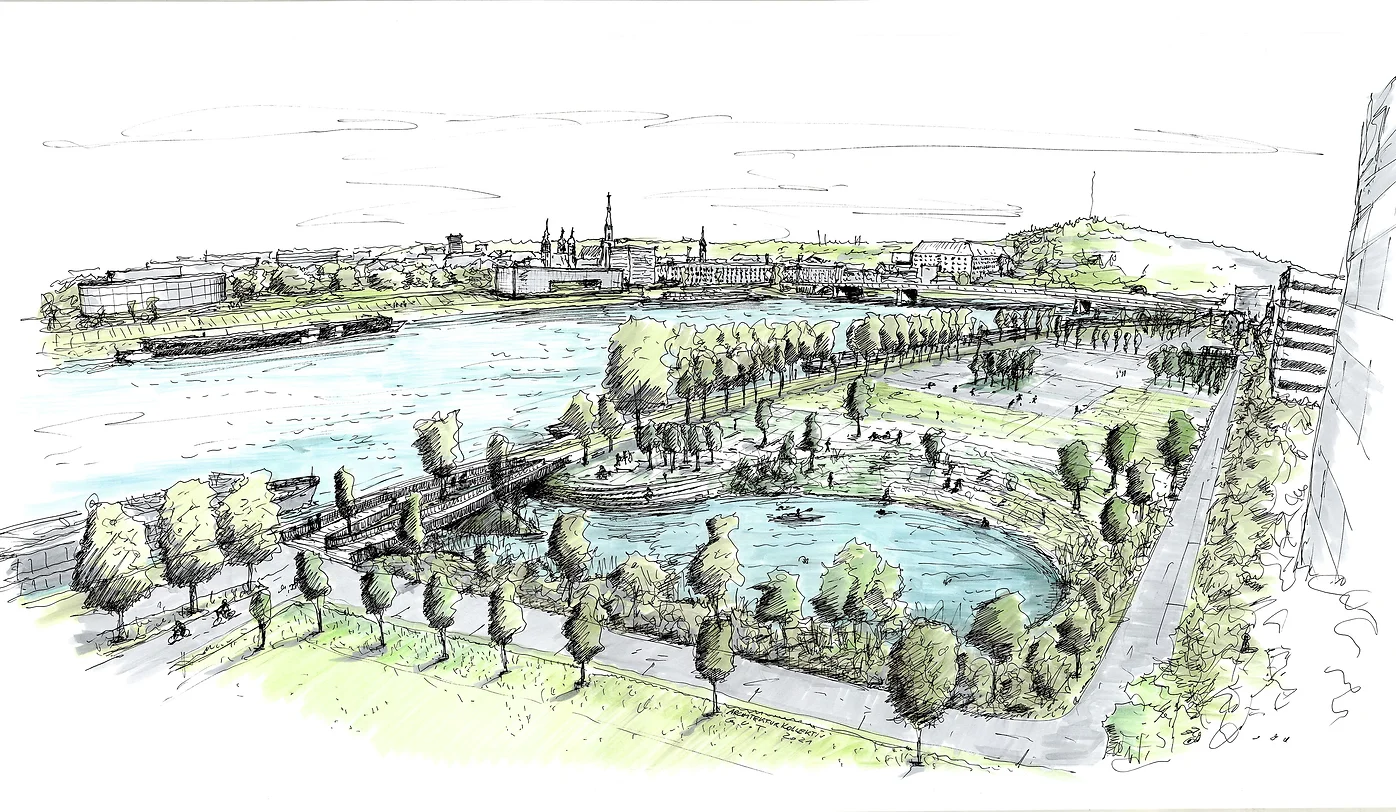

While conducting research on the area where we originally recorded the boat noise, we found that right across the Danube from where we were standing during the recording the construction of Linz Insel is being planned (Architekturkollektiv G.U.T, 2020).

At first, we were very enthused about the project: it was a promise for a greener, more aesthetically pleasing and potentially culturally enriching space instead of remaining a parking lot (Architekturkollektiv G.U.T, 2020). In effect, the project represents itself at first glance as precipitating resonance experiences.

Yet, the more we looked into the project the clearer it became to us that, viewed from a resonance-theoretical perspective, it has much less potential to add to a successful/fulfilling human life than it makes itself out to be. In fact, Linz Insel is supposed to be not an island surrounded by the Danube waters, but the same parking lot covered in grass with an alley around.

Whereas the noise pollution of the boat engine serves as a perfect example of how nature is being made available at the expense of human and non-human wellbeing, Linz Insel is a good example of how resonance is being commodified and made available to humans and how it is therefore diminished (Rosa, 2019, p. 469).

“The expectation of entering into resonance with nature on an organized safari or summit tour within a precisely defined time frame and under completely controlled conditions must necessarily be disappointed because the nature conceived as the counterpart here a priori loses its capacity to respond: The tour participant does not encounter an unavailability speaking with its own voice here, which can only be transformed under the willingness for self-transformation, but rather accumulates impressions” (Rosa, 2019, p. 469).

We argue that the project Linz Insel is mainly characterized by the aforementioned accumulation of impressions, as the idea for the project was conceived with a strong focus on urban development: “If there is one place along the Danube where there is an opportunity to generate intensive urban development, it is here” (Architekturkollektiv G.U.T, 2020).

Furthermore, it is characterized by a “banishment of the encounter with nature into temporally and spatially standardized and commodified resonance axes” (Rosa, 2019, p. 469). When for instance Linz "Island" project twists the meaning of an island, nature is being turned into an object of design (Rosa, 2019, p. 462). All of these factors contribute to the silencing of nature and therefore render nature unable to co-create resonance.

Voice of Nature

Conclusively, the superiority of industrialized sounds over those of nature as well as the act of commodification of nature and resonance itself, lead to a lack of resonance experiences. Adhering further to Hartmut Rosa’s theory, this in turn means that because of this lack of resonance experiences, the quality of one’s life is strongly diminished. At this point, it also becomes evident why it is important to question the way we relate to nature. After all, it has fundamental implications not only for nature itself but for human well-being.

While this paper criticizes the project Linz Insel based on resonance theory, it certainly does not intend to discard the idea of the project as a whole. Much rather it proposes that the current Western conception of nature and thus the lack of resonance experiences within our culture could benefit from a shift away from a capitalist, alienated relationship with the world.

In concrete terms, Rosa suggests, the aim is to strive for an active appropriation of nature, more akin to the relationship to nature of non-European cultures for instance (2019, p. 470).

How would our relationship with nature change if we were to conceive of it more like a living, breathing organism than a commodifiable object? The leader of the Palimiu of the indigenous Yanomami people of the Brazilian Amazon, for example, speaks of illegal gold miners leaving wounds on the earth (Forensic Architecture, 2022). Perhaps the first step towards a society that thrives upon a resonant relationship to the world, would be to acknowledge that one key to creating a cultural transformation may in fact lie in the way we perceive and thus treat nature.

Bibliography

[1] Architekturkollektiv G.U.T (2020). Vom Parkplatz zur Insel. Linz-Insel. https://www.linz-insel.at/vom-parkplatz-zu-insel

[2] Forensic Architecture (2022). Gold Mining and Violence in the Amazon Rainforest. https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/gold-mining-and-violence-in-the-amazon-rainforest

[3] Lessing, T. (1908). Der Lärm: Eine Kampfschrift gegen die Geräusche unseres Lebens. In J. F. Bergmann (Ed.), Grenzfragen des Nerven- und Seelenlebens (Vol. 9 (54), p. 1-94). Wiesbaden.

[4] Rosa, H. (2019). Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Suhrkamp.

Lea Giglmayr, Mira Prohaska, Pasha Dzyubenko-Kogan

Transformation Studies. Art x Science, die Angewandte, 2024