Tashkent(-Tbilisi). Grieving, drifting, healing

On the 1st of August, 2023, you added me as a friend on Facebook. You wanted to share an article, “The space that shapes us”. I was babysitting in a chic Parisian apartment, the child was snoring softly in its bed, I was myself about to fall asleep on the velvet sofa. I opened the link immediately.

In the article, Anastasia Galimova introduces notions of psychogeography, Guy Debord’s pioneer theory, and explores the legacy of the situationist movement. She connects this theoretical background to her own experience of drifting across Tashkent, the city she has inhabited since childhood, inquiring how different architectural structures make a neighborhood depressive, and another one a united, comforting commune. I finished reading, and texted you back that it had somehow consoled me from being about to go roam Tashkent streets, thousands of kilometers away from you.

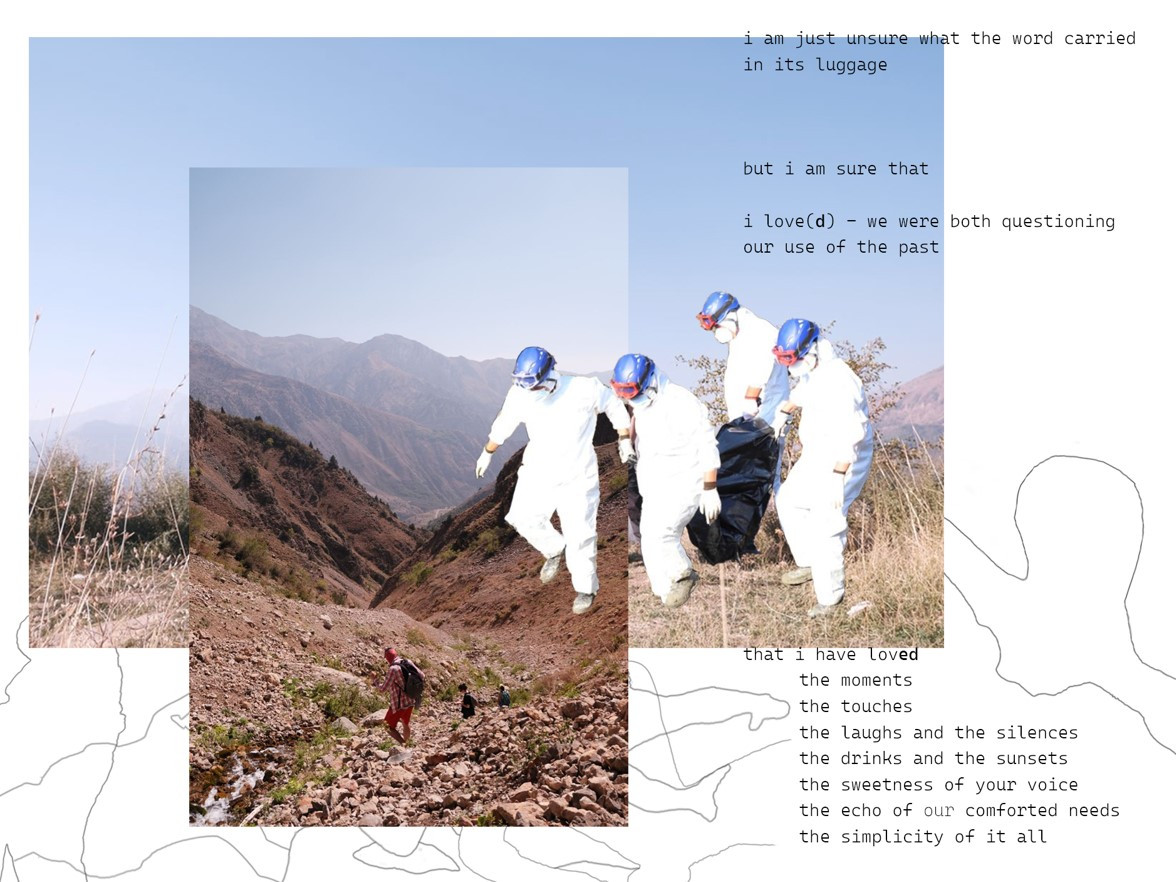

On the 3rd of August, you disappeared. Your body was somewhere, somewhere among the 5 million cubic meters of mud that devastated the picturesque resort of Shovi, in north-west Georgia. “Surrounded by evergreen forests, snowy mountains, it is the ideal place to get away from it all and focus on your own physical and mental health”, tourism websites write about the cottage where you spent your last hours.

Your name appeared in my Facebook notifications again. It was suddenly everywhere, hundreds of people clinging on to hopes that dwindled every hour. Your car was found, and then your best friend, and then you, Giorgi. It took almost another week to dig your sister out. Thirty-two deaths. Shovi was now “a great tragedy for the country”, your president declared. She came to your funeral. I did not.

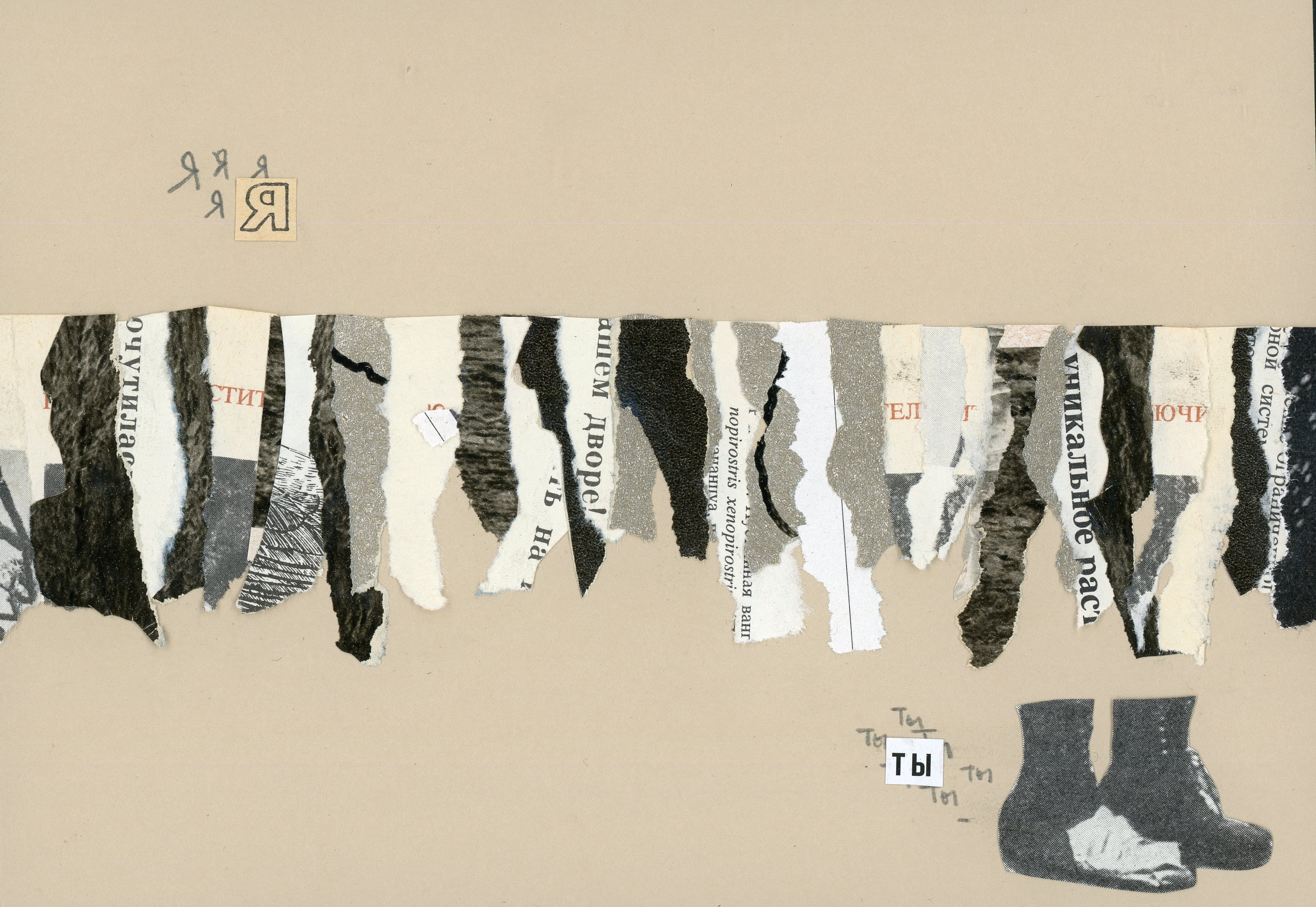

Now August is over and I am here, myself away from it all, eating warm lepyoshka in a cautiously refurbished apartment in the heart of Uzbekistan’s capital. I have moved a lot in my life, but what am I doing here? Now you are dead and perhaps it is not Tashkent’s fault, perhaps anywhere else in the world my presence would have made as little sense.

I wake up hazy. Each step outside reinforces a sense of disconnection I am very unfamiliar with. There are the wide streets and the Chevrolets’ honks, and here I stand. There is the dusty, polluted post-summer air, and here I am breathing. There are the washed-out turquoise mosaics of my building’s facade and here I stare, trying to picture the nuance of blue that covered your entrance door. I see the pepsi-cola ads, I see the countless unfinished hotels and the crooked sidewalks, and I see the ugliness of it all.

And I sit on my post-soviet balcony, a cigarette in my hand, thinking of those we smoked together at your window, half-naked in Saint-Denis. I watch construction workers building what will probably be another residence for overpaid expats, a new parking lot for expensive SUVs. I only read a few articles about the landslide. Probably, I did not feel a need to try to make sense of it. Still, a few words float in the background of what has become my life: climate change, erosion and melting glaciers; artificialization, post-independence unbridled capitalism, corrupt development plans. I stay on my veranda and some days I do not want to go out, I want to lay in bed, close to the few of your belongings I kept, trying to safeguard my physical memory of you.

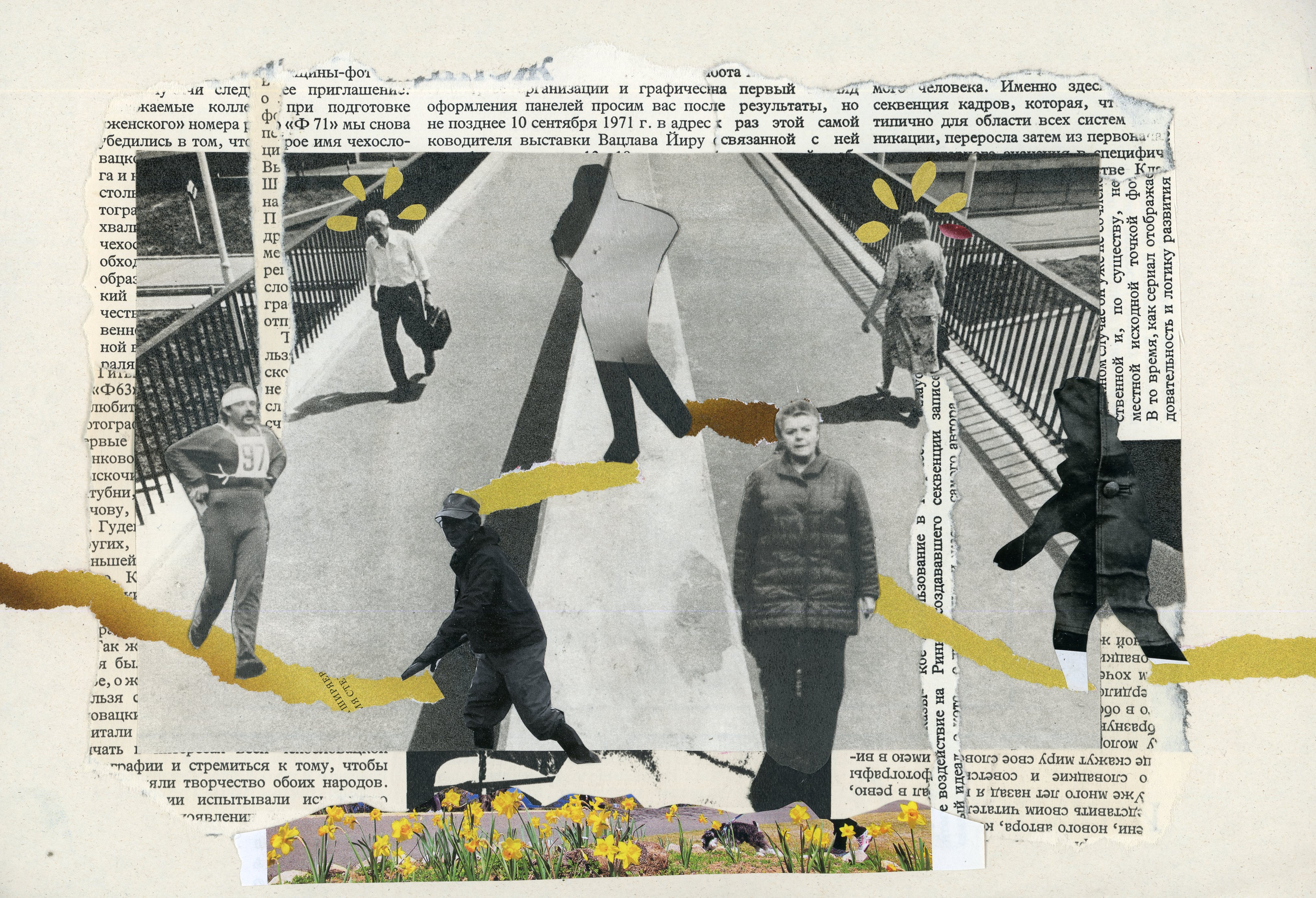

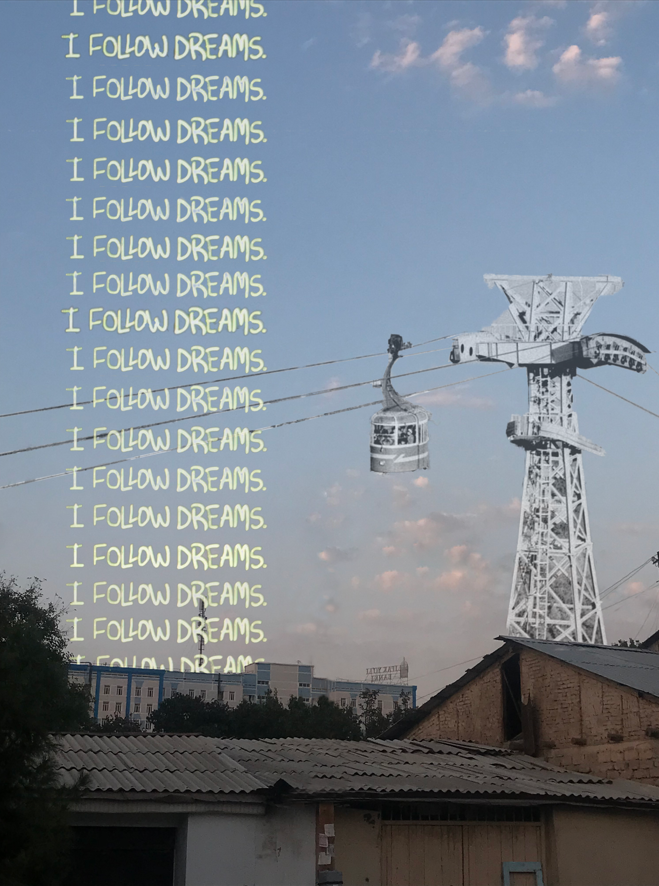

Time flies and summer fades away. I write dumb lists of things to accomplish — eat three meals a day, phone two loved ones, discover a new place this week. I walk to the supermarket and I walk to the swimming pool and I walk to the cafes and there are more and more crossroads I recognize. I can navigate the metro lines. At Kosmonavtlar, Yuri Gagarin waves at me, and I think back to this disconnection. It has been weeks, and haven’t I embraced it? Maybe because the empty streets leave so much space for your absence? Because I can miss your body as much as I want, unencumbered by any attachment to this place? Because I can inhabit my sadness and daydream in our memories, rather than immerse my body in the surroundings? Because I have nothing to demonstrate to this city, because even its buildings do not have a pretension for beauty? So I walk, and I am neither escaping nor exploring anything. My legs are moving, wherever they want to, and that is already something.

Time flies and one night, in an intimate techno club, I dance for hours holding your ID picture in my hand. Stroboscopic lights, muffled sounds and gin tonic — my mind and limbs enter another dimension. In the early morning light, I follow a boy I barely met. I hold this hand I do not know in neighborhoods I do not know. The soothing dusk light makes the brand new skyscrapers seem a bit more human. We walk by a canal, and for a moment I do not long for Paris anymore. I talk about you so much, Giorgi, about how I loved you, softly and too shortly, about how you died, about how sad I am of having forgotten the taste of your skin already. He tells me about his ex-girlfriend, about his car accident. At the foot of an absurd 65-meters high flagpole, I kiss him, and all I can think about is how small my body feels.

The summer is gone and anniversary dates go by — a month since I received your last text, two months since you stopped breathing, three months since your funeral. I often go to church. I light candles for Saints I do not believe in. I cross myself in the wrong direction, I do not dare to kiss the icons and through my drying tears, I laugh a bit at my own clumsiness. One day on my way back home, a child jumps out from behind a small tire workshop. He mistook my footsteps for his father’s. The surprise brings me back down to Mirobod.

I turn around and continue moving. The sunset is slowly settling in. I pass through posh neighborhoods, playmobil-like houses lined with the flags of the embassies they host. I cross another block of khrushchyovka, with its set of worn-out playgrounds that I have seen a thousand times, and that I continue to find moving. I arrive on a street that might have survived the 1966-earthquake, some crumbling family houses are covered with ivy.

Have I been drifting? I remember this afternoon well, because it concluded a week through which I had been so sad. I had been missing you and I was still missing you, every word I wrote was about missing you, I had nothing left to write and maybe nothing left to feel. So I drifted, and little by little, as I was filled by the sounds and lights of the city, my body felt a bit more real, in an environment, a place I had to accept as real, as my reality, far from the eternity where you now rested.

Anniversary dates pile up — three months since you stopped breathing, six months since I hugged you for the last time, a year since I met you, Place de la République. I did not go to your funeral. I did not go, Giorgi, but on that day, I bought myself a big bouquet. I do not know if you would have liked the flowers, but I took it in my arms and carried it across Paris. It was not a drift, no, I followed a precise list of places where I held your hand, places we had loved together, from Notre-Dame to Porte de la Villette.

I still sometimes watch the video I shot of that parade. Now I am here, in Tashkent, but soon I will be in Tbilisi, and I will meet the neighborhoods where you became you, and sooner or later I will be in Paris, back in the neighborhoods where an us was born.

I do not think I will miss these jammed avenues. But, I believe some of my pain might stay here, and probably I will always remember Tashkent with a peculiar form of nostalgia, and a peculiar form of gratitude, of thankfulness for offering me a space to heal.

But for us the road

unfurls itself, we count the

words in our pockets, we wonder

How it will be without them, we don’t

stop walking, we know

there is far to go, sometimes

we think the night wind carries

a smell of the sea

- Denise Levertov