Imperiya Refusenik

I am sitting in a Moscow-Tashkent bus that takes three and a half days to reach my destination. The time is approximate, because no one knows what will happen at the borders. And there are four of them: Russian for departure, Kazakh for entry, Kazakh for departure, Uzbek for entry. One can stand for hours. They say that people stand in traffic jams for days on departure from Russia. Besides, our bus is constantly stopped by the police. Someone wants a bribe, just like always. Others, to make fun of the “traitors” leaving Russia. They have no right to drop off people — there is no martial law. But they say there are some lists. And if they find you on them, they won’t let you out. The problems already begin in Moscow: at the MKAD (Moscow Automobile Ring Road), two young bearded men in plain clothes, apparently from the FSB (Federal Security Service), enter the cabin with the police. They ask the driver for the passenger list and immediately, on the second line, they come across my name. Not knowing that I am sitting right next to them, they start talking amongst themselves:

— Look: Kolya Smirnov. Is he fleeing?

— Fleeing!

Smirnov is statistically the most common Russian surname. Usually in Russia it makes me invisible, but this time it worked like a marker. They ask for my documents. They are surprised that I actually turn out to be a 40-year-old man. And that I have quite a few visas in my passport, including an open Schengen. I myself do not fully understand how it happened that I did not leave the country before or otherwise, because there was every opportunity. Perhaps, for some reason, I needed to drag out to find myself in this bus, which, filled with returning home migrant workers, 20-year-old Russian mobilization dodgers, and the cigarette smoke of incessantly smoking drivers, makes its way to Tashkent for almost four days.

The 14th edition of the experimental sound art festival Prepared Surroundings (PS) is held outside of Russia for the first time this year. Kazakhstan’s Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture brought the festival to Almaty as part of the 1st Korkut Biennale of Sound Art and New Music in Kazakhstan. PS curator and founder Sergey Kasich is in the United States. Another participant, Boris Shershenkov, comes online from Switzerland.

An irreplaceable participant of all PS editions, artist :vtol: (Dmitry Morozov) relocated to Almaty from Moscow six months ago, so there was no need to bring him specially. He is a very experienced and skillful sound artist, so he was called to be the technical director of the whole Korkut. This has clearly benefited the Biennale: the technical implementation is at a good level. Moreover, :vtol: complemented a number of projects with interesting artistic and technical solutions. For example, he helped to make a special instrument for qum.arna’s performance based on a gyroscope and Max/MSP program.

The relocation of :vtol: and the PS festival from Russia seems symbolic. For me it means the relocation of all contemporary art from Russia. At least the one we knew. As a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing conservative revolution in culture in the background of this war, Russian contemporary art, and with it to some extent all post-Soviet art, is undergoing a serious transformation. The Russian creative class is leaving for Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Georgia, Armenia, and Latvia. It is no coincidence that :vtol: at the closing conference thanks not only Tselinny CCC, but also all of Kazakhstan.

In addition to the relocated artists, Tselinny specially brought to Korkut Alek Petuk, Lovozero + Monekeer, vitalinair (Vitalina Strekalova). PS participants wrapped up the Biennale by showing a specially prepared program, as well as telling about the history of the festival and holding a closing conference. Together with the PS participants Anvar Musrepov, curator of the Biennale and a fellow-laborer of Tselinny CCC, sits at the table. From his words that the purpose of Biennale is to stimulate development of sound art in Kazakhstan, and from the fact, that he made a film about the PS while studying at Moscow Rodchenko School, it is clear, that the festival was brought as a sample of some long-term community initiative, programmatically directed on development of sound culture. But in this comparison Korkut looks conceptually more advantageous. In particular, it draws more explicitly on contemporary humanities theories, such as postcolonialism or new speculative philosophies. Whereas the PS existed more in the conceptual-purist traditions of the neo-avant-garde of the 1970s. The curator of the PS Kasich in Musrepov’s film also says this: “It may be retro-avant-garde, but for us sound is secondary to the conception of sound production. At the core of the PS lies the basic attitude that a new instrument or a new way of sound production gives birth to a new aesthetic.”

In this sense, the performance of the Tel Quel Experimental Sound Lab, led by Alek Petuk, is characteristic of the PS block. Twenty-four Almaty people responded to the open call, with whom experimental sound-gestural collective performances were created. The conception of one of them, “Horizontal/Vertical,” consisted in a reflection on different modes of organization: from “horizontal” free will and action to “vertical” instruction to action, for example, in the form of a melody. Actions of participants were distributed on four registers in a field between “horizontal” and “vertical” by means of color of screens. In another Tel Quel performance, a suspended plastic bag was “conducting” the gestural actions of the participants. The bag, in turn, was “conducted” by a fan. Petuk’s work in general is based on the absolutization of the method. In this case, from inside the system, the method is positioned as an avant-garde and “materialist revolution.” However, on the outside it is often perceived as a variation on familiar (neo-)avant-garde methods, indirect evidence of which is the name Tel Quel itself, which refers to the avant-garde structuralist project of the 1960-1980s. In this, Petuk succeeds to his teacher, Anatoly Osmolovsky, a classic of Moscow actionism, who continually reproduces the rhetoric and gestures of the avant-garde.

While Tel Quel seems to be a representative of “classical” PS, a kind of purist “retro-avant-garde,” PS as a whole are characterized by sophisticated but rather hermetic sound-artists, adhering to a strict conceptuality regarding media, objects and constructions. In contrast, Korkut relies on latest humanities theories, which makes it less hermetic-professional. In this sense, bringing PS to Korkut is beneficial in two ways: it demonstrates a culture of long-standing (neo-)avant-garde purism to the younger Kazakh sound art scene and shades Korkut’s fresher conceptual attitudes.

The Korkut Biennale connects experimental sound art with the audial tradition of local culture through the decolonial thinking. As the curator says: “Kazakh traditional culture is more audial than visual. But the transition to the audial avant-garde has not happened here yet.” The figure of Korkut (Korkyt Ata), a Turkic mythological musician, shaman and poet-demiurge of the 10th century, becomes the symbol of this correlation.

According to legend, Korkut wanted to achieve immortality. Believing that immortality lies in art, Korkut invented the kobyz, a bowed stringed instrument capable of producing a variety of sounds: howling like the wind or a steppe wolf, ringing like an arrow, crying like a child. Korkut sits down to play the kobyz at his birthplace, the lower Syr-Darya River. And while he plays, death has no power over him. However, at some point, after many years, he gets tired, falls asleep, and dies. Nevertheless, he finds eternal life in the spirit world and reveals the secret of immortality in memory through his service to mankind through art. Korkut leaves the kobyz to the people, an instrument that the baksy, Turkic shamans, began using because of its ability to imitate all possible sounds and thus be a method of “changing souls,” a shamanic journey between worlds. It also leaves people with healing music and a belief in the immense possibilities of art: while playing the kobyz, there were no mortals, but only happy beings.

The healing potential of sound is important to the organizers of the Korkut Biennale. The curator emphasizes that sound has a high potential for healing, referring to the practice of the Karrabing Film Collective and the texts of the anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli, stating: “one of the Biennale’s tasks is to activate magical thinking, to heal the soul.” I recall the idea of Gustav-Christoph von Gasfordt, governor of Western Siberia during the Russian Empire, that the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs are not so much Muslim as shamanists, and I ask Anvar how such an emphasis on the magical in traditional culture fits in with Islam. He answers that the magical in Kazakhstan is everywhere dissolved in everyday life. Strict Islam, in his words, appeared in the country rather with the collapse of the USSR, while historically Sufism has been more influential here. As an esoteric strand of Islam, the latter combines well with shamanism, so in everyday practices reading the Koran here is often accompanied, for example, by burning the “witch grass,” or adyraspan (harmel), which is used to cleanse people from evil spirits.

Traditional magical practices and contemporary artistic theories and practices often converge in their orientation toward healing the world. As anthropologist Michael Taussig has shown, the figure of the shaman in the modern world is inextricably linked to colonialism and the global hope for healing.[1] For Taussig, colonization has created a new global “space of death” — a physical and symbolic space in which the signs and symbols of the traditional space of the dead are intertwined with the death that capitalism and colonialism bring. As a result, signification is disrupted: the animist and shamanist falls into commodity fetishism, while the conventional “white” colonialist, afflicted by commodity fetishism, begins to suffer from haunting by evil spirits. A global hybrid (post)colonial spiritualist-capitalist space of death is born, in which we all now find ourselves. This space gives the shaman an increased power, constructing it in a new global status: now not only his former tribesmen turn to him, but also white (post)colonizers, who hope for a cure from commodity fetishism and haunting by the unquiet spirits of their colonial atrocities. The shaman, who has traditionally been able to navigate in the space of the dead, now does so in the new hybrid space of death as well, trying to cure the world of its syncretic diseases.

It is here where the reason for contemporary progressive theories’ interest in shamanism and magic lies. For Musrepov, as for many others, the magical is a variant of decolonial aesthesis, an indication of “other” worlds and knowledge systems that must be liberated from the yoke of repressive modernist unification, thereby healing the world. The curator of the Biennale continues: “The figure of Korkut has long attracted me with its magical decolonial potential, which I wanted to actualize in the context of contemporary progressive artistic practices. One of the Biennale’s objectives is to blur the boundaries between traditional culture, avant-garde and contemporary culture.”

The figure of Korkut is a good point of convergence of traditional local culture, sound art and decolonial paradigm. Because, on the one hand, Korkut is one of the key components of Kazakh and, more broadly, Turkic identity. A famous memorial complex has been built on the alleged site of his birth/burial, and in 2018 his legacy was included in the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage. On the other hand, Korkut is a symbol of music and musical experimentation, the patron of shamans and musicians. The narrative about him conveys a number of avant-garde attitudes, in particular the aspiration for universal happiness and immortality, as well as the belief in the special possibilities of art. Thus, Korkut’s name becomes the conception of the biennale of sound art and new music.

As Mark Weil, founder and the first director of the legendary Ilkhom Theater in Tashkent, who was killed by radical Islamists in 2007, wrote: “Many people who were rejected by Russia at different times found their place in Tashkent.”[2] This statement is true for all of Central Asia. However, today, against the backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the local art world is divided. Many take the position of principled non-cooperation with any Russians, including anti-war ‘relocants’ (relocated people). The Tselinny CCC is adopting a strategy of selective collaboration within the framework of the Korkut Biennale. In my opinion, this is consistent with its stated mission: to promote the local scene as well as to heal and help. After all, the power of the decolonial gesture is often not to establish opposition between the colonizer and the colonized, but to co-opt, to appropriate the language of the colonizer, irreparably transforming it from within. These subtle emancipatory mechanisms are discussed, for example, by Homi Bhabha in his theory of mimicry or by Derek Walcott in his discourse on the Muse of History.[3] As Walcott writes: desiring to purge the colonizer’s language from himself, the oppressed falls under the power of the Muse of History, which henceforth turns into Medusa, nailing him forever to the truth of his oppressed past and thus making emancipation impossible. Genuine liberation, however, lies in recognizing one’s own hybridity and harnessing the subversive power of the syncretic imagination.

Today relocants go to Central Asia en masse from Russia. These are very different people. Someone is fleeing from mobilization, but at the same time supporting Putin. Some are making a conscious gesture of “exiting” from present-day Russia, because they feel that they can no longer be in a society that is so saturated with imperial ressentiment and militarization. I call them the “refuseniks of the Empire” or Imperiya Refuseniks (uz). Such a gesture is performative, it is a transformation of one’s own identity, a play with its hybridization and queerization. There have been Imperiya Refuseniks among art people before. For example, Lawrence of Arabia or Usto Mumin, the early Soviet Voronezh artist Alexander Nikolaev, who moved to Central Asia in the 1920s, adopted Islam and a new local name. For me, a relocant from Russia, the Korkut Biennale becomes inseparable from the theme of Imperiya Refusenik. And even in those participants who are not relocants, I see manifest practices of rejection of Empire, simply expressed by other means, above all in conception and method. In essence, all progressive contemporary art is a project of Imperiya Refusenik, and precisely for this reason there is less and less room for it in contemporary Russia.

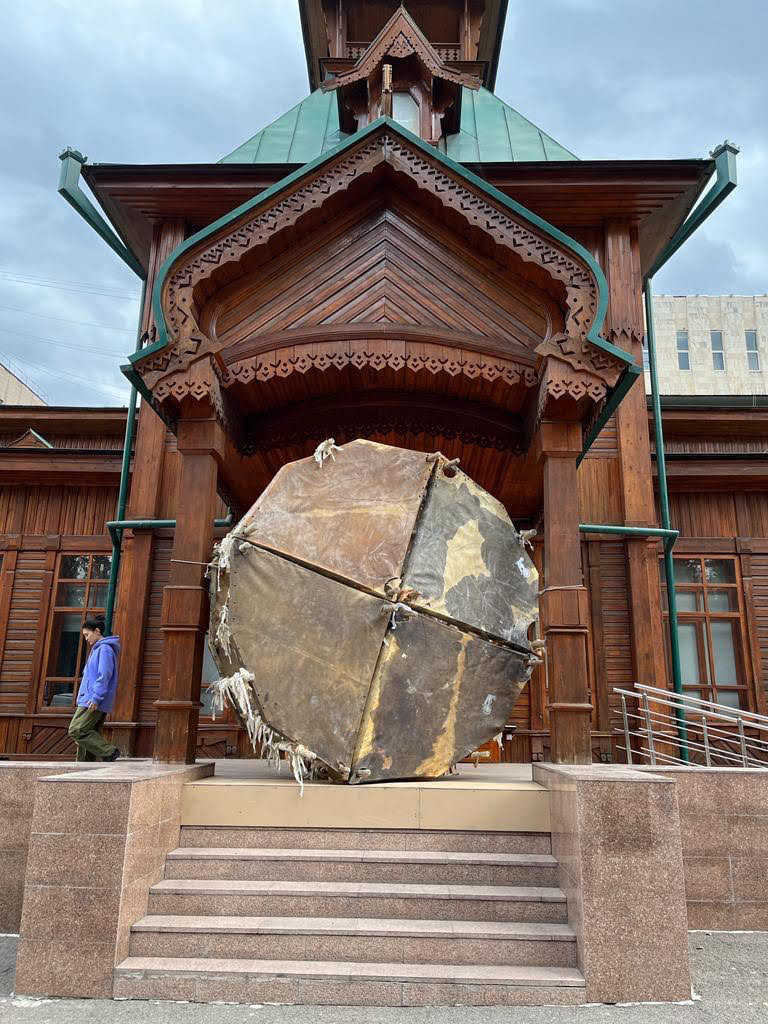

The central events of the Korkut Biennale are three concerts. The first, Korkut Sound, takes place in the Ykhlas Museum of Folk Musical Instruments, a “Russian style” terem built during the time of the Russian Empire. Interestingly, during the reconstruction in 1979, Kazakh national patterns were added to the wooden carvings of the terem. It can be regarded as a gesture of local attachment at the time of the global birth of post-colonial theory. Ykhlas Dukenov, a kobyz musician, in whose honour the museum is named, during the Soviet time was considered the one, who “first pulled out the kobyz from the hands of baksy and put this wonderful folk instrument with a human voice at the service of the new life of people.”[4] Soviet power sought not just to deprive individual baksy of power, but to lead the people to the realization that the people itself, in its totality, is the main baksy.

An 8-channel sound system has been installed for the concert in the museum’s chamber hall, an unprecedented event for Kazakhstan, according to Musrepov. In the center of the darkened hall, on a round stage, there is a performer surrounded by luminous “magical” devices. Kokonja (Darya Nurtaza), a young DJ and sound artist, opens the concert. She performs an improvised piece based on field recordings of wind made in different locations: inside a dombra, on a singing barkhan dune, and in the cave of Korkut himself.

Another young Kazakh sound artist qum.arna (Adil Kairden) presents a collaboration with kobyzshy (kobyz musician) Satkozy Mukhtar, a member of the contemporary music ensemble EEGERU. The latter, as part of the first phase of the work, experimented in the studio, trying to find a new atonal sound of the kobyz. The concert performance of qum.arna uses these recordings, but improvisationally transforms them with the help of different software.

The headliner of the concert is Chinese composer, media artist and researcher Hongshuo Fan, who is interested in combining traditional music and new technologies, in particular neural networks. On stage there is a dombra performer, Daulet Zhanshin, who engages in a sonic interaction with a neural network. The rivalry escalates into a battle, but it all ends in cooperation. As Hongshuo Fan says, “AI musician can be really attentive to human musician. So they can have a conversation.”

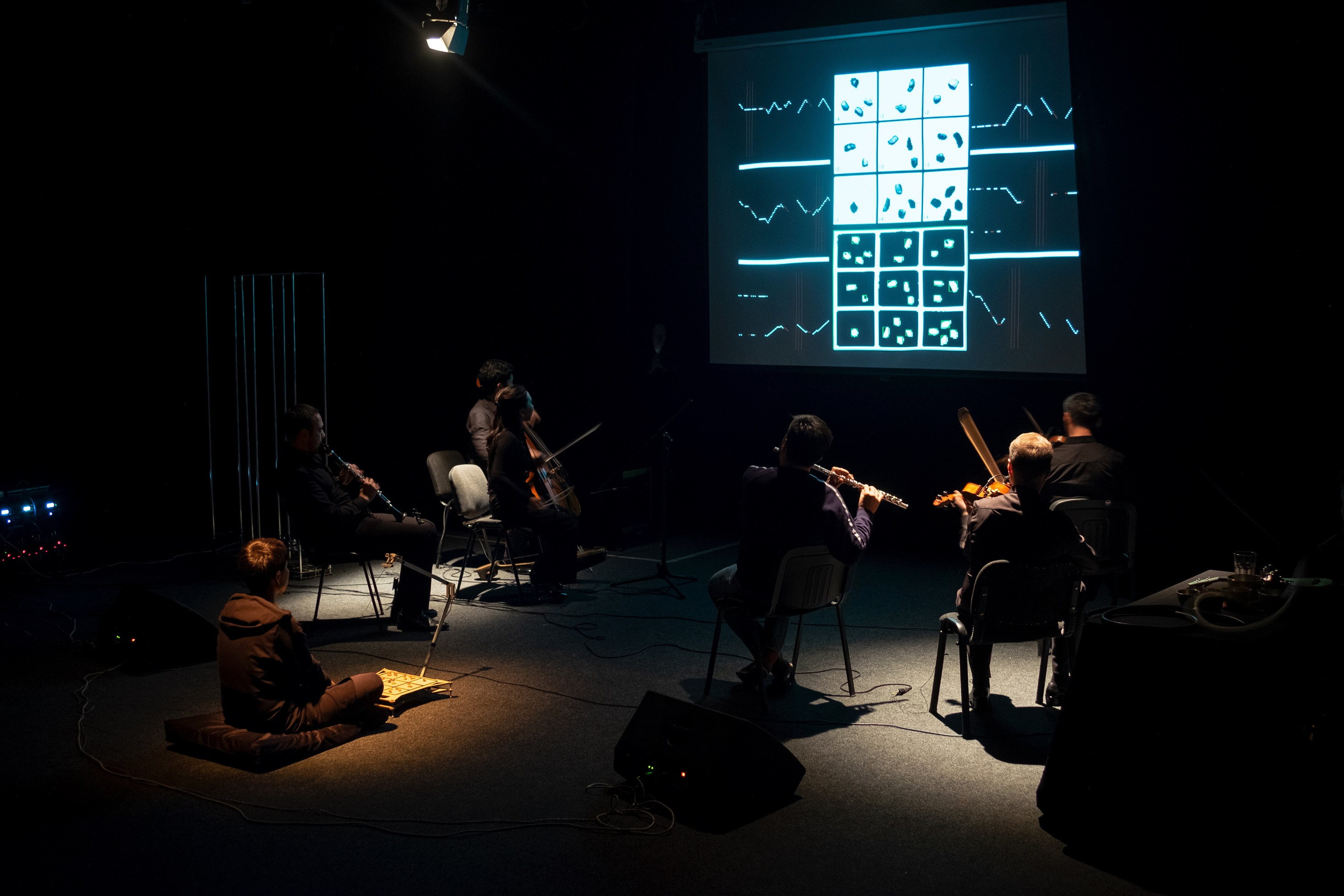

The second concert, Music of Fulfillment 41, presents a total sound performance combining technogenic sound, kumalak divination, and electro-acoustic music. A member of the techno-queer working group of bULt collective lays out a traditional Turkic divination kumalak on a special board. The program translates the layout into the scores for 6 musicians from EEGERU. Their performance is complemented by electronic sound from another bULt member, as well as the sound of “prepared” drones that move on vertical rods slightly off to the side. One of the authors of the conception, Asel Shaldibaeva from bULt, says that the concert is “an attempt to explore subjectivity as such… in an experimental field where we exclude free choice… and you are not the author, but part of the Great Process of Things.”[5]

In addition to the concerts, the Biennale has five installations in different locations. Uzbek artist based in France, Saodat Ismailova is showing her 2017 film Two Horizons, which is an artistic speculation on the theme of Korkut and cosmism. The artist makes the suggestion that Korkut wanted to overcome gravity to achieve immortality. Ismailova points out that the “navel of the earth” found by Korkut at lower Syr-Darya is very close to the Baikonur Cosmodrome, which sort of verifies or manifests in contemporary times her speculation about Korkut the cosmist.

The eight-channel audio installation Presence by the Berlin-based Kazakh duo the2vvo reflects on throat singing and the voice as an instrument of pan-unity. Traditionally, Central Asian throat singing was, like a kobyz, an instrument of soul changing in a shamanic trip, a technique for communicating with the natural and supernatural worlds through sound imitation. By means of the voice its possessor “left” the body for cosmic communication and was “reassembled” in it again into a physical presence. the2vvo not only extract the voice from the body, but also transplant it into a new digital device to complete everything as before, by resynthesis, but already inside a non-human medium.

Kazakh artist Dariya Temirkhan made a work based on field recordings of the Zhaiyk River, which for her “has always been a source of mystical power.” Kokonja’s installation in the Botanical Garden is the second part of her concert performance, presenting work based on field recordings of the wind already in stationary form. Interestingly, Kokonja is considered the successor of the school of Kazakhstani contemporary art pioneer Moldakul Narymbetov. This art shaman, philosopher and recusant was the leader of the famous art group Kyzyl Tractor. A separate exhibition curated by Vlad Sludsky is devoted to the sound art heritage of the latter at the Biennale. There are, in particular, musical DIY instruments that the group used in their (neo-)shamanistic performances. Overall, media shamanism turns out to be a common aesthetic and method that unites all the layers and meanings of the biennale: from Korkut and Narymbetov’s legacy to the techno-esotericism of the bULt club and the performances of young artists such as Kokonja.

The Kazakh departure border suddenly turns out to be difficult to pass. All holders of Russian passports are taken aside and questioned for a long time. “No Nazis among you?” — either threateningly or cheerfully, the border guard asks. I look at the faces of my fellow travelers: barbers, IT guys, managers, and designers, standing around the border guard with glassy, tired eyes. None of them are laughing. Finally, all the borders are passed, and by the end of the fourth day, our bus enters Tashkent. Two of the guys on the notorious list were dropped off at the Russian border, and the rest of us are entering a new life.

In Tashkent I am gradually “let up,” but not right away. The body produces a lot of energy in a critical situation, which is why many relocants are in a state of affective excitement for the first few weeks after their arrival. For the last six months in Russia I had a rapidly growing sense that we were not masters of our own lives. For me, a child of the 1980-1990s who grew up in an atmosphere of love in the family and relative freedom in public life, this had a depressing effect. This feeling is gradually disappearing here. My creative life here is already more intense than it was in Russia over the past year.

Of course, there are difficulties here, and not insignificant ones. In particular, many relocants, even anti-war ones, are carriers of unconscious imperial structures. Other relocants, more sensitive to critical theory, see this and seek to distance themselves from the “relocant” label. The only thing that these latter consider it possible to talk about now as conscious Imperiya Refuseniks is the various facets of decoloniality. But this is problematic because it is pointed out to them that their talk of decolonization must ethically be reduced to a process of decolonizing themselves from Russia. I understand this position and share the view of collective responsibility. But I think that the relocants in general have one strong point: they have already proved capable of performing the painful operation of distancing themselves and “withdrawing” when they fundamentally disagree with the actions of their country, which is fraught with a number of losses. But also a series of gains. In particular, the ideals of internationalism in a situation of relocation can be filled with real life content. After all, these ideals were born in a situation of conscious break with the imperialism and nationalism of one’s own country. “Own” is the key word for Imperiya Refusenik. After all, many of those who now rightly point to the responsibility of all Russians, have not themselves gone through a situation in which their country went mad, and who knows how they would behave, God forbid, if they found themselves in it. In any case, I want to retain the general right to speak about postcolonialism and decoloniality, which is realized, for example, in my text on the Korkut Biennale, though with what I consider to be necessary extensive contextualizations of the war in Ukraine and my own place of speech today.

Tashkent, November 2022

Translated by Denis Shalaginov

Notes:

1 — Michael Taussig. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987.

2 — Mark Weil. Ilkhom Theatre. Beginning. Available at: http://ilkhom.com/theater-ilkhom-beginning/.

3 — Homi Bhabha. Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse. In October, Vol. 28, Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis (Spring, 1984), pp. 125-133; Derek Walcott. The Muse of History. In What the Twilight Says, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998, pp. 36-65.

4 — Akhmet Zhubanov. Struny stoletij: Ocherki o zhizni i tvorcheskoj deyatel’nosti kazahskih narodnyh kompozitorov [The Strings of the Centuries: Essays on the Life and Creative Work of the Kazakh Folk Composers]. Almaty: Kazgosizdat, 1958, p. 229.

5 — From a video interview recorded for Korkut, courtesy of the organizers.