Sign of the Times # 4. Fragile Gift

The fourth dialogue in our “Sign of the Times” series of talks, in which we continue to talk about the role of memory and how art allows us to extend or shorten the time between us and history. The hero of this material is Jun Kitazawa, a Japanese artist who is actively working in Japan and Indonesia. In this issue, we will pay special attention to talking about a small, in duration, but large in consequences, period of Japanese colonial rule in Java. As usual, we do this through the artist’s projects, tying his personal experience and view of these subjects, which can be applied not only to a specific situation, but also events similar in nature.

A feature of Jun Kitazawa’s projects is his somewhat magical position as a conductor, which allows not only to gather people around him anywhere in the world, but also to restore the bygone eventfulness through projects that are oriented to the historical component. In many of his works, starting with “Living Room” or “My Town Market” (a project created to support people after the Fukushima accident), the artist seeks to create a place that would bring people together, and in the case of a second work, help to cope with trauma. People who join the stay have in his works not only an element of chance, but also ask the question of building a variant of a joint future that concerns everyone. For this reason, so often Jun Kitazawa creates specific venues (restaurants, portable nomadic structures, the “Five Legs” project), and stimulates his viewer to build cities. A final point that also seems worth mentioning is that many of Jun Kitazawa’s works are mirrored, whether you’re a foreigner in another country or just a person in front of a stranger — that’s the way we can look at ourselves, our country’s history, and eternal time.

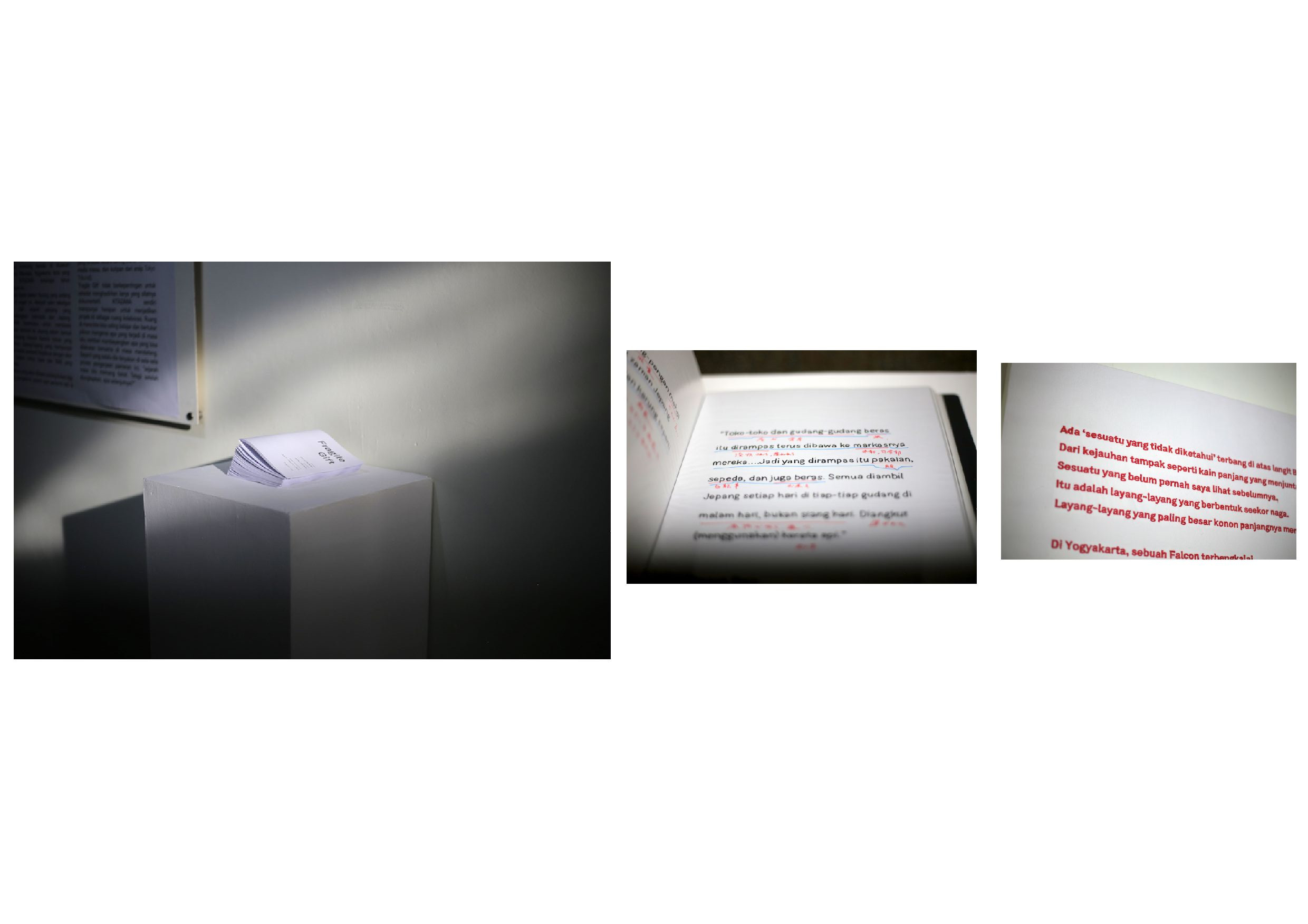

I sincerely thank Jun Kitazawa for our conversation and his help in preparing the material. We conducted the interview back in June, before the exhibition, which we will talk about in this material, but now a month later this material is supplemented by photographs from the opening of the “Fragile Gift” project, and the statement for this project can be read at the very end of the interview.

Russian version / Русская версия

Interview with Jun Kitazawa

Gendai Eye: If we start from the origins, then I would like to ask you if the subject of war sounded in any way in your family, and if it was discussed, then in what way? How did this subject move through your formative years?

Jun Kitazawa: The desk I used in my office in Tokyo was the one my grandfather used during his lifetime. He started a trading company himself and it is the desk he was using at that time. When I started the company to run my own art project, and was reorganizing it, a piece of manuscript paper came out along with the office supplies I was using at that time. I found it probably at the time of 2018 and read it last year when I returned to Japan. The title said “I know the war, but not the battle”, the grandfather’s own perspective is briefly spelled out because he probably belonged to the telegraph department and experienced the war during the war. I don’t remember talking directly to my grandfather about the war, but when I found this manuscript, read it silently, and handed it to my mother, my mother once again talked about the era of war and my grandfather. My grandfather died when I was in junior high school and I was thinking of war as a thing of the past.

GE: We have already said that you have a very rich experience of staying and working in Indonesia and Japan. Many of your projects are based on building connections between people, asking questions about identity and wondering what it’s like to be in countries with a different culture. Why is it important to be open to everything that is happening around, especially to those who are nearby?

JK: Throughout the project, I have consistently tried to ask about our “everyday”. Everyday life is an accumulation of experiences unique to each person, and at the same time, it is a physical memory that touches society and the world. Furthermore, the social system and common sense that surrounds oneself naturally continue to influence “I” through their daily lives. So to speak, the power from the society that makes me as me and that makes us as us is constantly being addressed throughout our daily lives. In Japan, where there are four colorful seasons and natural disasters occur frequently, it can be said that the daily activities that repeat every day are themselves a substitute for Japanese culture and have shaped the spirit. But at the same time, I also feel that the filter of everyday life, which is repetitive, is an excuse for us to be indifferent to the outside. At the same time as being close to everyday life, I ask questions about this everyday politics, shake the relationships and common sense that are close to me, and reconstruct the connections, as a practice to change that perception from inside to outside. I’ve been working on a project in order to question and deconstruct everyday life. It is inevitable to work in the everyday world, not just the world of art, which is open to others in front of us. A recent project to bring Indonesian everyday culture to Japan was a challenge to regain what we are losing in Japanese society by creating new routes from the outside to the inside.

GE: The topic of the colonial past is very important for talking about the formation of Indonesia in the form in which we have it now. Could you briefly, for our readers, tell the story of the occupation of Indonesia by Japan in the period from 1942 to 1945, what was the trajectory of these tragic events? [1]

JK: Currently, I am researching Indonesia during the Japanese colonial era for a new project. I’m trying to track down what things entered the life of the Indonesians after the Japanese occupation and why it happened. I came from Japan and am now living in Indonesia as a foreigner, so I couldn’t look away from this history.

The Japanese troops seized Java in March 1942. In order to advance the “Greater East Asia War”, the Japanese army took control of the lives of Indonesian people and tried to overwrite the Japanese way of life and thinking. They wanted to quickly use the rich resources of the land and combat personnel. In order to mobilize the entire society to war, they emphasized education and enlightenment, and transformed the village society of Java through preaching activities. The remnants of the Japanese military’s local policies at that time can be felt everywhere in Indonesia’s daily life today.

The form of the autonomous organization in the area where I live is based on the “Rukung Tetangga” that is absolutely similar and a literal translation of “Tonarigumi” [2]. The influence that remains now also makes us imagine the strength of oppression against the people at that time, and the “worker” who was forced to work remains as “Romusha” in Indonesian [3]. We hear about it every time when we unravel the experiences of these people and their families. In addition, I am forced into feelings of apology and sadness that are hard to express. At that time, there were many orphans not only because of the fighting, but also because of the deaths of their parents due to forced labor and the many people who could not return to their families.

GE: As far as the colonial past affects the country as a whole, Indonesia has a rich background in this regard, which included not only Japan, but also the Netherlands. Does this long absence of freedom and independence contribute to the emergence of politically difficult situations that happened in the country in the post-war period?

JK: There was a Dutch colonial era for three and a half centuries since the establishment of the Dutch East India Company in 1602. After Japan surrendered in 1945, Indonesia declared independence, and clashes began with the Netherlands, which embarked on re-colonization without admitting it. This so-called Indonesian National Revolution continued until 1949. In the meantime, Indonesia has a history of rebellion and coup d’etat, and tragedy has been reproduced. The difficulties of Indonesian politics are still ongoing, but to me it seems that the people are very sensitive and resistant to the apparent inequality of rights and concentration of power. It has been shown that it is more correct to continue to resist instability than to make inequality routine. It may be said that it is an objection to the structure of rule that is different from the colonization by foreign countries at that time. In that sense, the colonial past is influencing the present. One testimony record said: “Surely Japan taught us agriculture, but we never wanted Japan to be here in the first place”.

GE: How is the period of Japanese occupation perceived and comprehended in the artistic community within Indonesia?

JK: In April 1943, during the Japanese colonial era, the Japanese Army established the Keimin Cultural Guidance Center (Keimin Bunka Shidoso, 啓民文化指導所), recruiting some cultural figures and Indonesian artists who belonged to the military’s publicity department as members [4] . For example, the arts and crafts department actively held exhibitions.

So far, I think that the influence of art education through the recruitment of interns and public exhibitions held throughout Java had an impact on Indonesian art after that. I know that some friends of mine are doing pioneering and interesting research on the interaction between artists from these two countries under Japanese rule and their subsequent influence on Indonesian art. I can’t say that there is a common understanding of the art world during that time and I don’t think there are many ways to verify that time from the perspective of art history.

GE: In our correspondence, you informed me that for the past three years you have been engaged in research and preparation of a project that is dedicated to the topic of the occupation and the trauma that it caused to the people of Indonesia. What will your project be about and what is your goal, what do you want to tell?

JK: As I did earlier, I have realized projects across Indonesia and Japan in the past few years, and I am preparing research on Java under Japanese occupation and projects based on it, starting from some kind of self-criticism through them.

This is a project named “Fragile Gift”. The concept started in 2018. The fighter “Ki-43” used by the Japanese army in the 1942 invasion of Java was called “Hayabusa” (“Falcon”), and was used by the Indonesian National Revolution in the Indonesian National Revolution after the surrender of Japan. There are currently 12 existing aircraft in the world, one of which is in Yogyakarta, where I live now. I also go through that place once in a while.

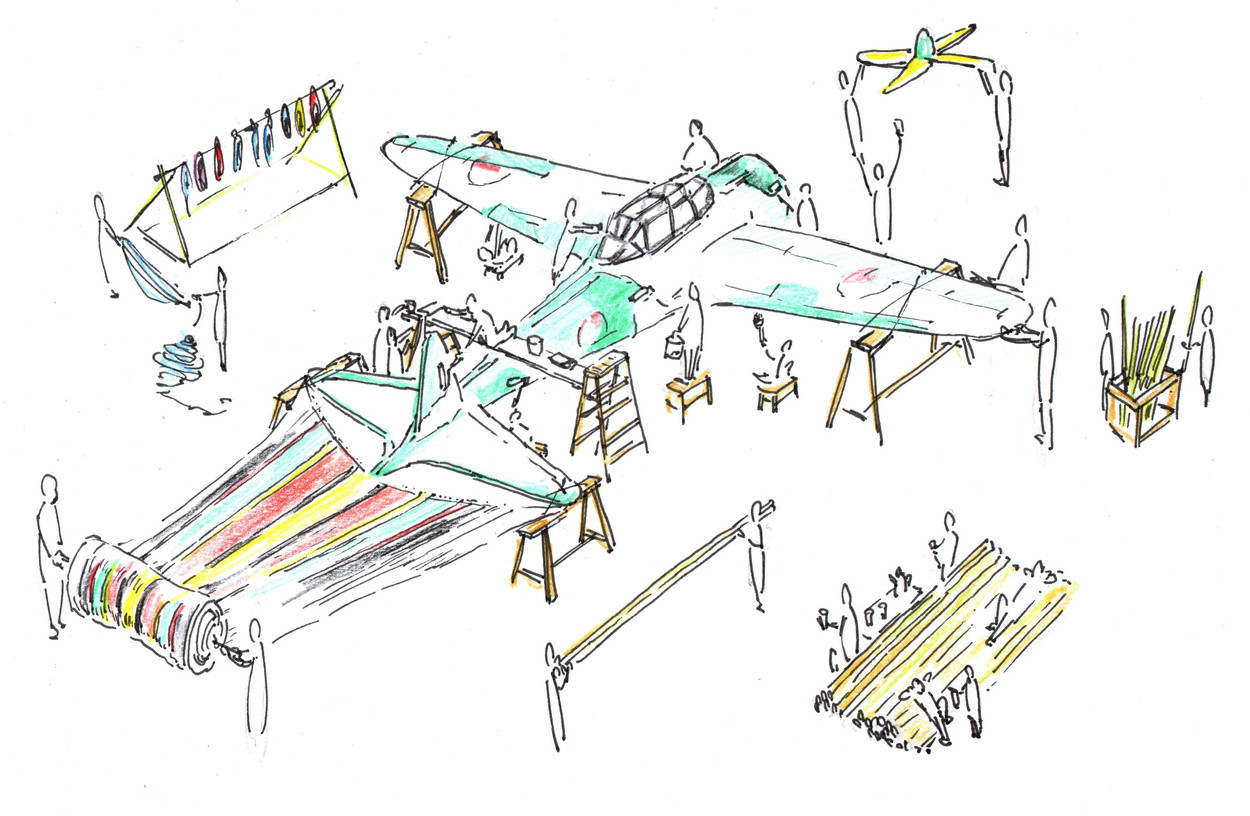

In Bali, next to Java, there is a custom of raising a kite in the shape of an abstract “dragon”. This kite, which represents the mythical dragon king “Nagaraja”, can reach up to 150 meters in length and fly in the sky, requiring many hands of islanders on the coast. The appearance of it is stunning. I am trying to fuse this “Falcon” and “Dragon” with “Fragile Gift”. The body of the falcon and the tip of the dragon are overlapped, and the tail of the dragon made of a long and colorful cloth is overlaid with the words of the Javanese people collected from the records at the time of the occupation. In other words, the falcon’s body becomes one with the dragon’s kite, and the dragon’s tail is the orbit of the falcon and becomes the path of people’s memory. Contrary to the route that came from Japan to Indonesia due to the invasion of Java, I will make this work using bamboo and cloth as materials in Indonesia, and finally aim to fly it in the sky of Japan.

“Fragile Gift” starts from the fact that my personal dilemma of being Japanese and living in Indonesia overlapped with the “non-moving aircraft” that was brought in by Japan and used by Indonesia. What should we make together in these two countries now? Through this project, I will face the dilemma of myself and history and try to answer this broad question. This project turned the Japanese awareness of the remaining occupational memories and its impact on everyday life in Indonesia, and created time to look at the works that dance in the Japanese sky with Indonesian migrants living in Japan. I want to actually draw a symbolic landscape that connects two countries and others.

GE: How do you plan to build a dialogue with the audience of this exhibition, can they have any claims against you?

JK: Project will be open to the public from July of this year, so let’s see what happens. Currently, I’m working on a project with my Indonesian friends and doing research, and as I talk to them about records, there’s always something that weighs heavily on myself over time. It may be the “weight of responsibility”. The mass of testimony and records is much larger than the work of this project. Throughout the project, I will only be able to take a serious approach to its size, think about how it should be shared with others, and continue to find ideas. However, I still do not give up hope by trying.

GE: What would be a significant difference in the presentation of the project in Indonesia and Japan?

JK: The main venue of the project is not the exhibition room, but the everyday space of both countries. Of course, different rules and powers are working, so the way they are treated will change. It includes politics, but I want it to arouse the curiosity of children and adults, rather than the method of raising the message loudly in the sky, because you touch the history that was far away. There are various taboos in Indonesia that are not limited to war, but artists in this country continue to create works in the midst of their inconvenience, believing that they should reach someone through their works. I hope that this project will also appear in everyday life in such a “gentle but dangerous” form. “Fragile Gift” means fragility and brittleness, but at the same time, it is also used to indicate “Handling with care!”. As a gift with such duality, I would like to deliver it to someone who has not yet seen it.

GE: Responsibility trail, how many generations do you think it could affect? Should young people, for whom this war was a long time ago, continue to carry this burden? Or would it be better for them to keep the personal history of their family, to know their past?

JK: The story goes beyond generations. Like the songs. In my research, I met a lot of Javanese people who squeeze Japanese songs. When I hear it, it says that it’s a song that my grandfather and grandmother sang to their parents. That’s just the influence of the occupation, but what I’m trying to say here is that while it may be difficult to change the status quo through art, it has the power to recreate the story and tell someone who can’t meet now. I think there is. A young man 100 years from now may fly “Fragile Gift” into the sky as a daily festival. Then they will meet new me and the past. I want to bet on that encounter.

GE: After the Japanese occupation, not such a long period of time passes, the generations that witnessed the war are still alive, and the situation with the neighbors reappears, only in the opposite way. I mean the occupation of East Timor [5] . Why is this happening so soon, does the experience of blood and suffering fade before revanchist sentiments and the desire to get rid of the status of the victim and the affected country?

JK: Aside from thinking about the perpetrators and victims of the Japanese-occupied Indonesia, there is a similar problem in East Timor under the Indonesian occupation. The issue of Papua is also often seen in Indonesian news [6] . Colony, authority, independence, war. I always hesitate to deal with this problematic system, which makes me feel that it is too dangerous to use structural thinking. If we look at it structurally, it would be more about the system of the state. COVID-19 seems to have spread fear throughout the world and, as a result, exposed us to the weaknesses of the border-separated nation system. Too much I don’t know yet about the colonial issues of East Timor and Indonesia. Even if you don’t feel like it, you need to know more about the second president, Suharto, after the first president, Sukarno, who supported Indonesia’s independence. The village of Godean, where he was born, who ruled the dictatorship for 30 years, is only about 15 minutes drive from his house.

GE: What lessons does history give us and why do we not want to learn? What can a simple person do in this situation?

JK: It’s been 20 years since I discovered my grandfather’s memoir, read it as a thing of the past, and talked with my mother about it as a thing of the past. A few years ago, when I started researching in Indonesia, I was in the mood to see the occupied records as a thing of the past. However, one day an old man who experienced a war on the streets of Java suddenly hugged me and said, “Japanese are friends”. I was upset. What does this mean? Certainly, there are as many historical perspectives as there are people. An elderly woman I met in another city said, “I was scared, pretending to be a boy to protect myself”. I continue to be upset. This is because my skin directly touched what I thought was in the past. Meeting them is the source of the current project. Instead of reading the past and talking about the past, creating a moment when history comes into contact with the skin. That may be one of the things we humans should do from now on.

The Statement of Fragile Gift

This is the story of three elders.

The first one walked barefoot through the rice fields in the mountains of Bumiayu, one of the sub-districts in Brebes Regency, Central Java.

Hundreds of ducks followed behind him.

The ducks looked adorable as they walked, squawking and waddling.

He is a duck keeper. He led the way while holding a thin bamboo stick with a red and white flag on its end.

When I stayed at his son“s residence, I learned that he was almost 90 years old. With my Indonesian still stammering, I asked him:

“How was life in the Japanese era?”

“The Japanese are my old friends”, he replied.

The 88-year-old woman is my friend”s grandmother. She lives in Bandung, West Java. Her grandchildren speak Indonesian, English and Chinese fluently.

As we ate dinner together, we chatted and laughed occasionally as we commented on her portion sizes, which had not decreased at all. She was also the one who decided and ordered what we should eat.

After the meal, I asked her the same question.

“I’m scared”, she replied immediately. I tried to capture her emotions with my limited vocabulary. She told me that when she was a child, she cut her hair short and dressed as a boy to trick the Japanese soldiers.

While strolling through Solo, Central Java, I came across a small tower at the end of the street. An old man selling retail gasoline by the roadside approached me. His skin is tan and wrinkled with age, but he still looked sturdy. He was wearing a yellow T-shirt. He explained to me in Javanese about the tower in front of him, but I could barely understand him. When we were about to part, he realized that I was Japanese. He looked very emotional and hugged me. I hugged him back thinking why he was hugging me. “Japanese people are my friends”, he said.

Every time I asked that question, every time we had a dialog, I felt something was off. Fear, and at the same time, the feeling that I was facing a very important situation. Silence. I felt confused during and after listening to their story. Even now.

I see how humans should live day-to-day on this tropical island. I try to create something from that perspective. What if I see myself from a distance? What if someone from Japan tried to bring something to this country, or vice versa, to get something from this country? There were times when I consciously wondered if perhaps I had unwittingly repeated “those times”. In other words, what I have been doing as an artist could structurally overlap with the Japanese colonial period. I finally decided to start confronting this dilemma, which had been weighing on my own mind and perhaps on the minds of others.

–

There was “something unknown” flying over the skies of Bali. From a distance it looked like a long cloth dangling and hovering in the air. Something I had never seen before. It was a kite in the shape of a dragon. The biggest kite was said to be 150 meters long.

In Yogyakarta, an abandoned Falcon. A Japanese Ki-43 fighter aircraft also known as Hayabusa (Japanese for “falcon”). It was used during the Japanese invasion of Java. After three years of colonization, it was repainted and used during the Indonesian War of Independence period. One of the 12 remaining Hayabusa planes in the world is in the aviation museum in the city where I live now.

The Balinese dragon kite frame and the Falcon fuselage are roughly the same size. I combined the Naga and Falcon into one. I tried to imagine the scene when the kite was flying and painted it. It feels like a new “unknown” has been born, hovering languidly between the two countries and their histories.

It will be made in Indonesia, then transported and flown in the skies of Japan. Can it be sent as a “gift” and be accepted by the people there? The kite is made of light and fragile materials, but the history and memories piled up on it are very heavy. Either way, it must be handled with care.

What had the Falcon sent from Japan to the island in 1942 seen? It wasn’t just the fighting. The effects of the occupation, which lasted only three years, were so profound that they still linger in the daily lives of the Javanese. Compared to the magnitude of the life transformation and trauma caused by the Japanese military’s demands on Javanese society at the time, this project is still small.

The “Fragile Gift” project will attempt to symbolically return a lost eagle in the form of a dragon. This is a “gift” that has passed through time for 80 years.

15 June 2022.

Jun KITAZAWA

—

[1] The Japanese occupation of Indonesia lasted three years, from March 1942 to August 1945. In the period before the Japanese invasion, the country was a colony of the Netherlands, so at the end of the Pacific War, the Netherlands again expressed its desire to return Indonesia. Sukarno, the first president of independent Indonesia, declared the independence of the state, which led to a long armed conflict between Indonesia and the Netherlands / Great Britain. During the hostilities, according to various estimates, from 25 to 100 thousand people died. Only on December 27, 1949, Indonesia was recognized as an independent state.

[2] “Rukun tetangga” is a tracing phrase from Japanese that incorporates the meaning of “tonarigumi” (隣組). To simplify the understanding of this expression, it is rather an administrative unit that is managed by active village members or a village union, focusing on effective self-government and resolving issues within the Indonesian community.

[3] “Romusha” is a word that is used in relation to those workers who performed tasks not of their own free will, but under duress. During the war, this word was fixed in Indonesian, having received a very negative, but rather even tragic connotation. It should also be taken into account that the romusha had to work not only in the territories where they lived, but also in those regions of Indonesia (or other countries of Southeast Asia), where they were sent by the Japanese administration to build the necessary facilities or perform certain works. Most of them died during these labor trips, only a small part of the people were able to return back to Indonesia after the Pacific War and the Indonesian War of Independence.

[4] A little more about the role of the Japanese administration in the formation of Indonesian art can be found in this material (in Japanese)

[5] The history of East Timor is also full of tragedy and a horrendous number of victims among the local population. The island was under Japanese occupation during the Pacific War and returned to Portugal after 1945. Only in 1974 did the movement towards the independence of the island begin, by 1975 the declaration of independence of Timor was issued, but 9 days after that, Indonesia invaded the country. Only in 1999 will a referendum on independence be held and in May 2002 East Timor will become an independent state. But the story for East Timor does not end there, the consequences of a colossal period of radical transformation from one regime to another, as well as the theme of the colonial past, still keep this country very firmly in a difficult political and economic situation.

[6] Relations between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, with all the rest of the difficult foreign policy baggage, are also one of the unresolved problems that do not disappear from the political field. The conflict revolves mainly around refugees from Western New Guinea, who are trying to preserve their own identity and culture, so they often cross the border and stay in Papua New Guinea, which in turn has caused dissatisfaction from Indonesia for decades.

Sign of the Times:

— Sign of the Times # 1. History and disposal container by Yoshinori Niwa

— Sign of the Times # 2. The Trajectory of the Family Past by Aisuke Kondo

— Sign of the Times # 3. Pointing at the history by Kota Takeuchi

— Sign of the Times # 5. Restoring time by Hikaru Fujii