Mirage on the Bed of the Aral Sea

In November 2020, the second part of the Main Project of the VII Moscow International Biennale for Young Art opened at the Museum of Moscow, where Olga Shurygina presented her video installation “Mirage.” This project was inspired by the artist’s trip to Uzbekistan, where she headed off with a plan to lay three thousand ceramic plates out on the floor of the dried Aral Sea. The Cultural Creative Agency curator Vera Trakhtenberg spoke with Olga about the artist’s adventures and Uzbek hospitality. We are also publishing a video that has become a central part of the installation, which serves as additional documentation of the process of the creation of the art piece.

VERA TRAKHTENBERG: Olga, why did you choose the city of Muynak for your project? How important is the role of environmental disasters and the fall of the eastern lobe of the Aral Sea level in 2014 (it has turned into a desert) to your work?

OLGA SHURYGINA: At some point, I realized that I needed to expand the circle of my interests. Earlier, I was mainly focused on the topic of female symbols, and “Mirage” definitely continues this line. As a woman and as an artist, I come to the city with a camera, open for experiments. What does being a female-artist mean? What does it mean to arrive at a new place where you have no contacts or opportunities and attempt to bring your idea to life? I chose to follow my intuition and did not know beforehand how everything would end up.

The preparation of the project began two months before my arrival. I found out about a local electronic music festival that was held right there, at the dried bottom of the Aral Sea, and thought it would really be great to do some kind of installation for this festival. First, I wanted to do something visually simple, but at the same time exciting, but soon it became clear that I wanted to realize this very idea: to come to Muynak, invite each local resident to share a plate, and use these plates to lay out a mirage on the dried seabed. The organizers of the festival found my idea very strange and even risky and suggested postponing the implementation for a year, but I had already bought the tickets and firmly decided to go to Muynak.

The issue of ecology is not the central one in my statement. I read that the sea dried out largely due to natural causes, not because of human impact. And although it did influence the local climate, my primary interest was related to people. They used to live by the sea, but now they are surrounded by the desert—this is what made an impression on me.

VT: How did you come up with the idea to interact with the locals and involve them in the process of installation creation?

OS: I wanted to get to know Muynak residents, to observe their life and at the same time share something of my own. I offered them something, at first glance, totally useless, something one cannot make money on, and received an incredible response—not only from adults, but also from children.

VT: Could you, please, tell us how you managed to convince people to participate in the project?

OS: I showed them sketches, explained what I wanted to do and why, talked about myself and a little bit about art.

VT: Did anyone refuse to join?

OS: Yes, some of them did, but those were very few. Basically, it was men who explained that their wives were not at home and they could not give away dishes without their consent. They feared their wives would scold them. It looked funny, since many consider Uzbekistan to be a country with a very patriarchal way of life. But at the same time, there is really a very secular approach to many things: women dress up and do not cover their heads, men drink alcohol, although Islam does not approve of this.

VT: How much time did you spend in Muynak collecting plates for the project?

OS: Precisely twenty one days. But it was enough to see some kind of result. The events were unfolding rapidly: the Deputy Prime Minister spoke about my project on Facebook and people from all over the country began to send me dishes.

VT: How did you manage to get your actions coordinated with the authorities? After all, you were travelling without preparation.

OS: After seeing the project, someone asked me, “You probably had everything coordinated in advance?” But when I came to Muynak, I didn“t even know where I would live. I would describe it all as a series of nonrandom coincidences. I didn”t even have a translator from the Karakalpak language, which is spoken there, and I don’t know Uzbek either. I kept it in mind that I would have to act on the spot and the experiment turned out to be a success. As soon as I arrived, I ran into some kids: in Uzbekistan they learn Russian at school and it was easy for me to communicate with them. I told them about the project and they volunteered to help. We spent the whole day visiting their friends and acquaintances and talking with the locals. When the kids were busy, I continued on my own, literally knocking on the doors of strangers and asking them to give me plates for the project.

VT: How did you manage to collect more than three thousand plates in twenty one days?

OS: It did not happen very fast, at all. At some point, I took a calculator and tried to figure out how much time I would need to collect the necessary number of the plates—two months! This was time that I obviously did not have. I convinced myself I would come up with a solution later, and then, quite by accident, I was invited on a tour around a new garment factory. It had just been opened and everyone was waiting for the visit from the leadership of Uzbekistan. The next day, the president arrived: the whole city was closed. Then I found out that the factory employed three hundred and fifty employees, so I talked to the production manager and she promised to help—however, in the end I had to communicate with the employees myself. I spent the entire week visiting the factory every single day at lunch breaks telling the women about the project.

The language barrier problem was solved by recording the translation of my speech on a voice recorder—in one cafe I met a Russian-speaking woman (Amina Bekzhanova), and she agreed to help me by allowing me to record her voice. Moreover, she turned out to be the owner of a local hotel and invited me to stay there for free. I politely refused, but Uzbek hospitality really impressed me! That woman sent her sister Dulfuza Kutlymuratova who not only brought me to the hotel, but also arranged a meeting for me with the mayor of Muynak!

VT: Sounds like a fairy tale!

OS: It does, doesn’t it? Then there were meetings with the head of the tax service and the head of the local police.

VT: It was not your first trip to Uzbekistan, but you went alone in an unfamiliar city. Some would say that for a girl it can be dangerous to go to such a place on her own. Weren’t you scared?

OS: Muynak is a city on the outskirts of Uzbekistan, close to the border with Kazakhstan. I have been to Tashkent, but everything is completely different there. Yes, it was scary, but my fear was caused by the stories of those who moved from Uzbekistan to Moscow: they said that the attitude towards a lone tourist from Russia might not be very positive. My grandmother was very much worried and asked me to cancel the trip. But there were also other opinions—no one had even done this before, so people might just have any idea of how to react, but there was nothing wrong with that. Uzbekistan, like many other countries, looks completely different for different people: some have a positive travel experience, some do not.

Everything that happened to me in Muynak looked like an adventure or a movie, but it definitely was not a nightmare. For example, Amina Bekzhanova (the locals called her “Amina Pa”), the owner of the hotel, wrote in her Telegram channel that an artist from Moscow was collecting plates for the project. Local bloggers were subscribers of her channel and so, through a chain of reposts, the news about me reached the Deputy Prime Minister of Uzbekistan. Learning from his post on social networks that I needed help, the locals began to collect plates, as it got to federal channels. At some point, all the collection of plates got out of my control, and I turned into an observer. The Ministry of Tourism reached me saying, “Olga, there are a thousand plates for you!” The plates turned out to be new, because they simply would not have had time to collect the old ones. This upset me a bit, as it went against my plans, but I remembered that I myself was only an observer and certainly accepted them. I even managed to get permission to shoot the installation from a drone—something almost unreal for a tourist, but they did me a favor.

There were other incredible ideas I was able to bring to life. In the film, there is an episode where I talk to the pupils of a local school. It is very difficult for a tourist to get such a permit, a stranger cannot step into a classroom and tell something to schoolchildren, but the city administration helped me with that, too. The central Uzbek television channel also made a feature about the project—and it was a completely new experience for me. The whole project left me with a lot of interesting material in general , some of which came unplanned: seventeen hours of footage—a real anthropological study. Many things remained in memory only.

VT: Your project is a complex and not entirely clear installation that functions in the space of contemporary art. People not involved in the artistic process may react neutrally or even negatively, but in your case, many Muynak residents agreed to participate and give away something very personal—plates that they eat from daily. Why, in general, did you decide on an object like plates to be laid out on the dried seabed?

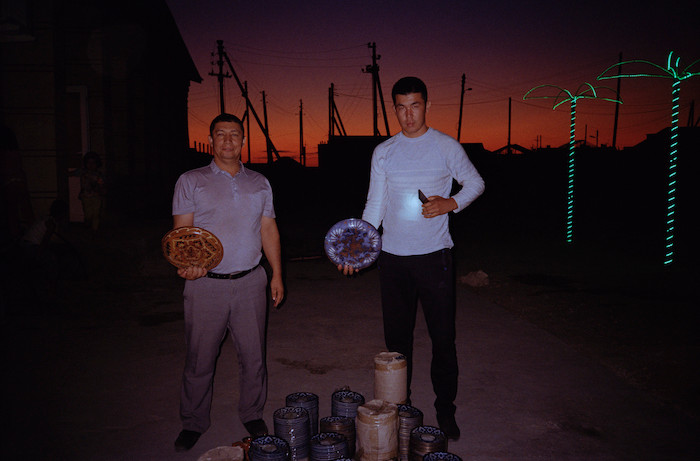

OS: A plate is a recognizable symbol, a tourist souvenir. A memory object you feel like taking home. Uzbek ceramics can hardly be confused with any other—it is an ornament, a form, and a texture inherent in the local culture and craft traditions.

VT: The title of the project is “Mirage,” a phenomenon caused by the upward refraction of light in the atmosphere. Could this mirage be created elsewhere? Or is there a historical connection with Muynak and the Aral Sea? Is there any reference to local traditions or rituals in the project?

OS: There are different types of art: one is built on logic and historical facts, and the other—on personal experiences. “Mirage” has become my personal story, reflecting the transition from the material world to the poetic, imaginary world. I process my personal fears and show other people that it is possible to do. In my earlier projects, I already worked with plates as a form and symbol of home comfort, hospitality, and everyday life. In Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, there is a tradition of bringing ceramic dishes to graves. People turn plates upside down and leave them on tombstones, sometimes filling them with water first. No one knows exactly where this ritual originates from, but they continue doing what their ancestors did.

VT: People brought different plates: old and new ones, more expensive and cheaper ones. But, laid out on the seabed, they become a memorial, and any differences get erased but a statement remains, resembling a mosaic in form.

OS: The project might have turned into something completely unpredictable. It was interesting for me to observe what kind of plate this or that person gives. Some wanted to give the best, others, on the contrary, gave away the broken dishes, because they felt it was inconvenient to refuse. Someone gave out old children’s plates their family members no longer needed. It really sounds simple, but a plate symbolizes a person. This is how I explained it to the locals—that it is either about the symbol of a family or of a person.

VT: How many people are there in Muynak?

OS: Officially, more than thirteen thousand, but I’m not sure that so many people actually live there.

VT: What happened to the plates after the shooting?

OS: As I explain in the film, it was impossible to leave the plates there, so I collected them the next day and put them in a local tourist yurt. It was in September 2019, and I planned to return to Muynak in February to continue working on the project, but due to everything that happened in 2020, I did not get to Uzbekistan and the plates remain there now. I really want to come back and keep on working on the story, but everything depends on circumstances. I have an intention to continue collecting the plates, maybe even on the scale of the whole country and set a new record. It is difficult to predict what material it will turn out that I have in the end: a full-length film, a huge memorial, an exhibition—or even all of these.