Photography as a Distorted Mirror: Viewing War and Its Mediated Realities

Photography, as one of many mediums of expression, possesses a distinct set of conventions and a unique way of constructing messages. The expressive possibilities within its visual language are traditionally determined by four main characteristics: plane, frame, temporality, and focus. However, it is important to note that photography, throughout its systematic development since the second half of the 19th century, has incorporated stylistic elements from other mediums such as mannerism, modernist formalism, cubism, abstraction, and performance. This expansion of artistic techniques has allowed photography to move beyond mere imitation or the transmission of “incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened” [Sontag, 1977, p. 5]. By the beginning of the 20th century, the photographic surface emerged not only as a mirror reflecting “reality” but also as an interactive “screen” projecting various cultural visions and identifications [Gombrich, 1963].

While the prevailing function of metonymy (as detailed by Roland Barthes) or substitution in the analysis of photography has been subject to skepticism regarding its explicit spatio-temporal fragmentation [Pfister and Woods, 2016; Metz, 1985; Bazin, 1980], the potential of photography as an imaginative surface can be revealed through implication [Stanley Cavell, 1979]. This allows the viewer to access the realm of previously invisible or “outside of the image” phenomena [Barthes, 1981, p. 87].

Stanley Cavell’s observation that “The camera, being finite, crops a portion from an indefinitely large field… When a photograph is cropped, the rest of the world is cut out. The implied presence of the rest of the world, and its explicit rejection, are as essential in the experience of a photograph as what it explicitly presents” is significant [Cavell, 1979]. This statement challenges the interpretative model that focuses solely on the photograph as an indexical reference to the event (“having-been-there” [Barthes, 1956]). It suggests that the potential of the photographic space extends beyond functions of memory-keeping and truth-telling [Berger, 1972]. Instead, the frame of a photographic image is viewed as an entry point to a deliberate cultural process of creating meanings and symbols. This departure from the metaphysics of judgment (“myth of photographic truth”) invites researchers to immerse themselves in the entire space with which photography interacts and even shapes, emphasizing the importance of production, haptics, perception, and the viewer’s engagement as integral elements in the process of photographic signification. Consequently, the photograph, constantly alluding to its absent other [Hoelzl and Marie, 2015, p. 40], loses not only its frame but also its transparency for the viewer, making it an exceptional research material from psychoanalytical, sociocultural, and anthropological perspectives.

In the realm of documentary photography, often criticized for its dramatic and propagandistic nature, the ambivalence between the visible and the invisible, the present and the absent, becomes crucial in defining the representational boundaries of photography as a medium of war. In terms of documentary criticism, the value of a photograph as a document lies not merely in its exact rendering of the referent but in how it is perceived and interpreted by the observer. This raises the question of what determines a particular “presence” for the viewer, even if the image itself does not depict specific individuals. Susan Sontag’s ethical consideration of photography as “a medium that does not rape or possess but may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, metaphorically, assassinate” highlights the importance of distance in the perception of photographs [Sontag, 1977, p. 24].

The notion of distance is central to understanding the limits of representation and its influence, as the physical separation between the spectator and the depicted events (war) allows for mediated interpretations of these events. No photograph conveys its connotations in a vacuum [Caroline Brothers, 1997, p. 20]. The more interpretation applied, the less presence remains in the photograph, as content begins to dominate the space. However, perceiving photography as an integration, characterized by the presence-in-absence structure proposed by Alva Noë, enables a shift in the viewer’s role. The viewer, appreciating the continuity of life experience, becomes dependent on the pictorial space offered by the photograph rather than the interpretation of the image itself. In the context of conflict photography, this aesthetic perception allows for a sensory experience of the presence of war, even in its apparent absence from everyday life, by evoking sensory triggers and speaking to the face of trauma [Gumbrecht, 2008].

An illustrative example of non-referential interaction with photographic space can be found in the field of “operative images” [Farocki, 2004, p. 17]. These images are not captured through traditional documentary shooting by human eyes but are instead produced using technologies that simulate human vision, such as drone photography, surveillance cameras, and webcams. The key aspect lies in the fact that people interpret these “god’s eye view” images with reference to preexisting subject-object relations, ready-made forms of power, morality, stereotypes, and clichés.

For instance, the photograph titled “Children” [see Fig.1], captured by the Maxar satellite after the attack on the Donetsk Regional Academic Drama Theatre in Mariupol on March 16, 2022, gained iconic status as an object-symbol. It transcended being merely one of many city series documenting the aftermath of shelling, and instead conveyed the essence of war from an inaccessible aerial perspective. It is challenging to pinpoint the exact elements that give this image its iconic character—the deliberate inscription of “children” [Russian: “deti”] in front of the theater, addressing the enemy, the external media context that informs about the loss of civilian lives, or the collective effect of indescribable tragedy. While it can be argued that this example also serves as undeniable evidence of war crimes, what remains significant is the underlying regulation of the viewer’s imagination. As Laura Kurgan noted regarding satellite imagery of mass graves in Kosovo, “Beneath or beyond the limits of visibility, of data, are the dead. And yet they remain in the image, in the ruin of the image, and ask something of us” [Kurgan, 2002, p. 655].

The image from Mariupol is not the only example where photography has become a tool for visual communication with a “do-something!” effect, altering viewers’ perspectives on war from the standpoint of survivors [Balabanova, 2017]. Certain images have the ability to convey more than words alone, guiding viewers towards interpretations shaped by the maturity of the historical moment itself [Petrovsky, 2012, p. 137]. Two photographs that simultaneously depict the onset of the war serve as a powerful example. The first photograph, captured by a surveillance camera on the Russian-Ukrainian border [See Fig.2], provides visual evidence that the media’s headlines about the outbreak of war are not “fake news” and that the threat is real. The second image [See Fig.3], illustrating the catastrophic situation on the roads of Kyiv, serves as a narrative continuation of the first photograph, revealing the tangible consequences of Ukrainians’ awareness of the hostilities. In this way, the seriality of photography transcends the temporal and spatial constraints imposed on individual images, creating a cohesive narrative that aligns with the medium’s unique temporal and spatial parameters. As Hariman and Lucaites suggest, still photographs, despite their lack of motion, can effectively communicate a sense of potential energy [Hariman & Lucaites, 2016, p. 253].

Operative images, in the context of war, do not conform to the typical documentary style of sharp, front-line combat photographs but rather embody what Hito Steyerl has referred to as the “poor image” [Steyerl, 2013]. These abstract visual representations, with their imperfect performance, deviate from accurate object representation, which paradoxically enhances their medium’s expansiveness.

Their (operative images) potential for aesthetic experience lies more in sensory perception than appearance. Consequently, the image constructed from such photographs primarily resides in the viewer’s imagination, relying on preexisting meanings known to them. Thus, the image functions as a flexible and permeable surface open to subsequent manipulations aimed at establishing a stronger connection with the recipient, rather than a monolithic construct imposed upon them.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that photographs of war, despite their endeavors to transcend their own medium, do not provide spectators with a comprehensive view of the unfolding events. As Purgar notes, “The event cannot be visually unlimited, and the consciousness of the difference between here and there must be retained” [Purgar, 2015, p. 57]. In other words, pictorial presence is not a prerequisite for perceiving the image, and maintaining a certain distance from the subject is necessary. Technological advancements may broaden the spectrum of the visible, but the viewer remains the essential participant in the process, capable of redirecting or even challenging the intended focus embedded within photography, allowing them to see beyond the surface and recognize imposed citations, power relations, and impact factors [Bottici, 2011, pp. 60-61].

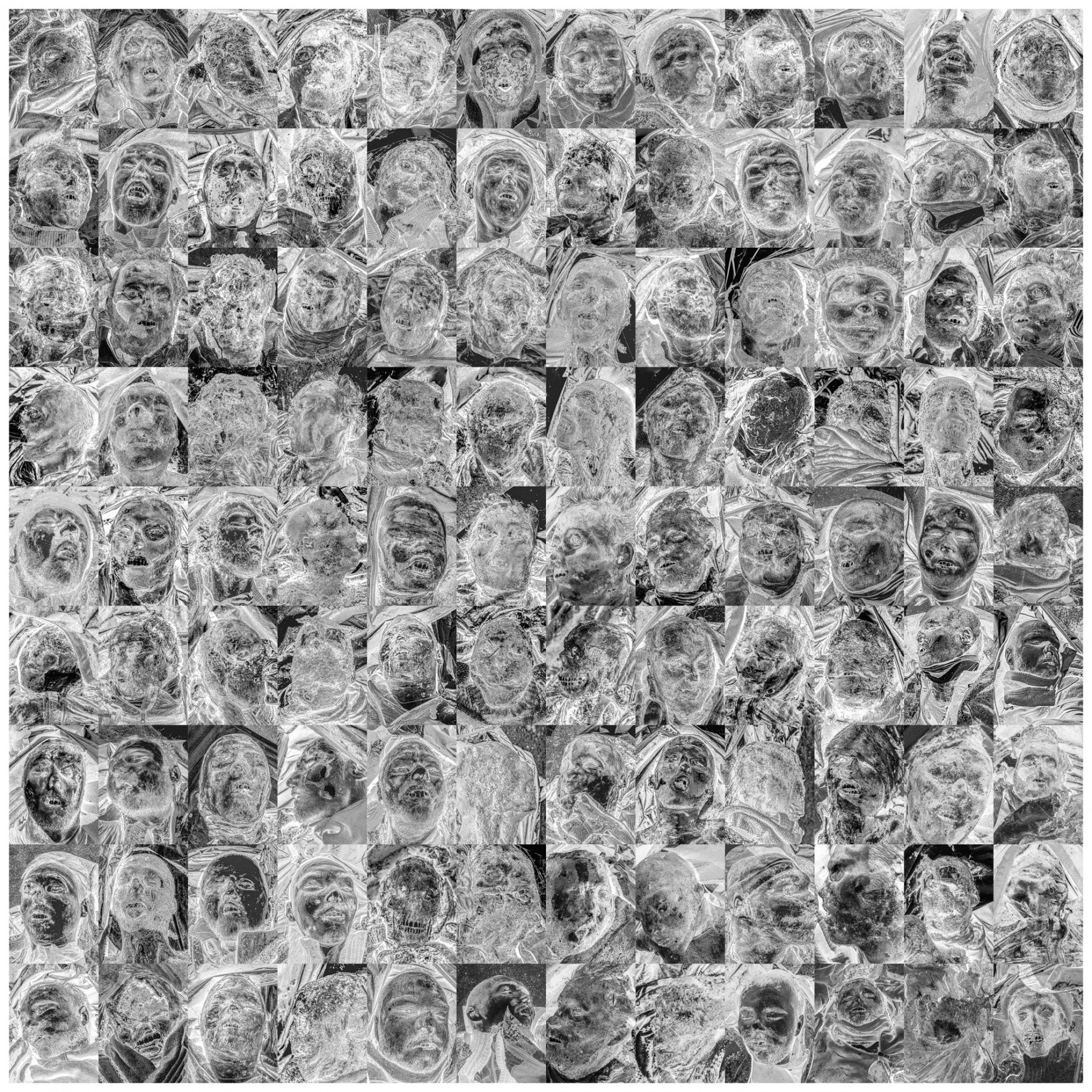

For instance, consider the collages assembled by Antoine d’Agata from dozens of portraits of killed soldiers taken in morgues around Kharkiv [See Fig.4]. On one hand, this practice of depersonalizing the victims may be viewed as provocative or mocking of the deceased. However, when examining this series of photographs beyond its specific time period and as an image of war, it becomes apparent that the collage serves as an allegory for the Soviet military code “Cargo 200” (Russian: “Gruz dvesti”), highlighting a semantic connection to past conflicts such as the Soviet-Afghan war and the Chechen Campaigns, where soldiers were similarly mistreated by the Russian military command. In this context, the representation functions more as a metaphor for institutionalized violence rather than an individual testament to a fallen hero.

These examples demonstrate how photography’s role in war extends beyond simple documentation or representation. It operates as a potent tool for communication, inviting viewers to engage with the imagery, encouraging interpretation, and evoking emotional and intellectual responses. Through the integration of personal meanings, sensory triggers, and the viewer’s imagination, photography facilitates a profound engagement with the presence of war, enabling a deeper exploration of its complexities and the boundaries of its representation.

These findings highlight the complex nature of photography as a medium of expression, demonstrating its ability to go beyond being a passive reference to events or an objective representation of reality. Instead, photography functions as an imaginative surface that interacts with cultural processes, evokes meanings, and shapes viewer perceptions. By considering the role of distance, interpretation, and the integration of personal meanings, photography becomes a powerful tool for engaging with the presence of war, even in its absence, and exploring the boundaries of representation in the context of conflict.

Considering the aforementioned examples and recognizing their exceptional nature, it becomes evident that war as a whole remains largely undocumented. Conflict photography tends to capture highly specific and unique cases that demand the viewer’s attention. Moreover, photographers often serve particular institutions that align themselves with one of the parties involved in the conflict [Mirzoeff, 2016]. Consequently, the visualization of war primarily serves the interests of the war and its perpetrators rather than representing it on behalf of the indirect victims. However, the role of war photography extends beyond mere news reporting and the documentation of war crimes. At times, it assumes a more artistic dimension, challenging conventional approaches to representing death and the losses inflicted by ongoing conflicts.

Photographs of war, subjected to distortions and manipulations, take on the characteristics of simulacra—signs without a clear signified, pointing to something that does not exist [Tagg, 1988, p. 63]. By examining a collage created by war photographer Paolo Pellegrin, one can gain an alternative perspective on the individuals involved in the conflict, even though the photograph itself lacks identity [See Fig. 5]. The viewer is denied knowledge of who stands before them—whether it is the hero or the enemy, the victor or the vanquished. Ultimately, war reduces everything to faceless remnants, a mere collection of human bones, reminiscent of Vasily Vereshchagin’s painting “The Apotheosis of War” [See Fig. 6].

In both Pellegrin’s collage and Vereshchagin’s painting, the individual’s identity is subsumed by the collective impact of war. They serve as visual representations of the devastating consequences of conflict, emphasizing the dehumanizing nature of war itself. These images prompt viewers to contemplate the anonymity and universality of suffering, transcending the boundaries of individual identities and highlighting the shared experiences of those affected by war. By removing the specifics and personal narratives, these visual representations invite viewers to confront the larger themes and human costs inherent in armed conflicts.

The discussion refers to the affective potential of war images, particularly those labeled as “about-to-die” images [Zelizer, 2010, p. 309]. These photographs evoke strong emotional responses in viewers, but without accompanying context, they may fail to provide concrete information or nuanced understanding of the complex realities behind the images. This highlights the role of the viewer in engaging with and interpreting war photographs, either by accepting the implied narrative or by questioning and conducting further investigation.

Conclusion

War photography holds a significant place in documenting armed conflicts and shaping public perceptions of war. The power of visual imagery to communicate the horrors, realities, and consequences of war is undeniable. Throughout history, photographs have served as powerful tools of visual communication, evoking emotional responses and compelling viewers to take action.

Photographs from conflict zones, such as the striking image from Mariupol, Ukraine, have the ability to transcend language barriers and convey the urgency of the situation. They can evoke a “do-something!” effect, prompting viewers to question their own attitudes towards war and inspiring them to advocate for change. These images have the capacity to communicate more than words, capturing the viewer’s imagination and inviting interpretations informed by the historical moment.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of war photography. The images that emerge from conflicts are often highly selective, capturing exceptional cases rather than providing a comprehensive portrayal of the entire war. Photographers are frequently aligned with specific institutions or parties to the conflict, shaping the visual narrative to serve their interests. This can result in a skewed representation that works in favor of the war and its perpetrators rather than shedding light on the experiences of the indirect victims.

Moreover, war photography is not solely confined to objective documentation and evidence of war crimes. It can also assume a more artistic approach, challenging conventional representations of death and loss. Through distortions and manipulations, photographs can become simulacra—signs that lack a clear signified, representing something intangible. By depriving images of individual identities and reducing them to faceless remnants, photographers like Paolo Pellegrin draw attention to the dehumanizing effects of war and invite viewers to confront the collective impact of conflicts.